Have you ever donned aVR headsetand climbed up a mountain likeVesper Peakin HTC Valve’sThe Lab? It is a truly exhilarating experience, one where you can almost feel the fresh mountain air filling your lungs (and not the rich aroma of an office like in reality). But when you’re standing on the edge of a sheer mountain drop, no amount of convincing yourself that you’re actually on terra firma can prepare you for the feeling of vertigo you experience. Stepping over the virtual edge? No thanks.

In this situation it is difficult to make that leap of faith, so is your brain at fault for keeping you frozen to the floor? A new study,publishedin the journalHeliyon, usedvirtual realityto see whether the emotional responses limiting how much we explore an environment (such as a fear of heights) are simply affected by the environment, or whether there is an influence the brain makes based on its perception of the body and space around it.

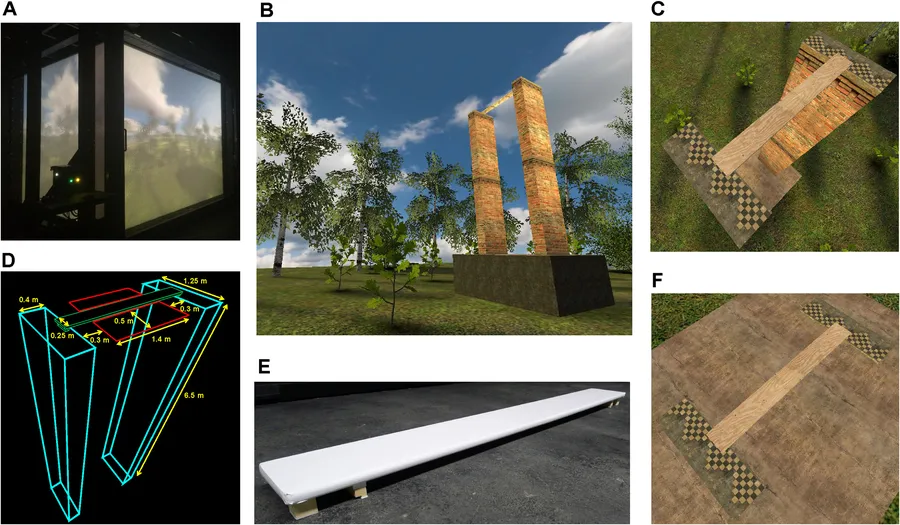

Dr Martin Dobricki from the University of Würzburg in Germany tested the theory by putting volunteers in a life-sized virtual forest and had them walk a virtual plank. In the virtual world, this plank was either on the ground or high up, precariously balanced between two walls. In the real world, the plank was either flat on the floor, making it stable, or (this time securely) balanced slightly off the ground, making it bouncy.

What they discovered, perhaps unsurprisingly, that when virtually high up on the bouncy plank, the volunteers had an overwhelmingly negative experience, spending more time looking at the space below. Conversely, when the bouncy plank was on the ground, the subjects spent more time looking up and exploring the world above the horizon.

"Our research shows that we are not stimulus-response machines; our emotions and our behavior are both based on the interdependent perception of ourselves and the world," says Dr Dobricki.

These findings should be of particular interest to anybodywithphobias, especially those looking to treat a fear of heights. Adding a bouncy floor to any therapy could intensify the experience and maximise the therapeutic effects.

"We hope that our findings will inspire other people to look at the body-environment interaction we have identified. For example, experiments like asking people emotion-inducing questions while they sit, walk or swim could result in many interesting and surprising findings and might lead to totally novel techniques for managing emotional response."

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard