A few steps away from the busy streets of central London there’s a room that’s familiar to millions of people around the world; the steep rows of seats, the polished woodblock floor, the large desk. Each year for nearly two hundred years, a scientist has walked into this room to enthuse and enlighten the young audiences who flock to this Lecture Theatre for the Royal Institution Christmas Lectures.

Afternoon lecture courses for adults had run at the Royal Institution (Ri) since 1800, but in 1825 the first lectures aimed at young people were launched. Originally, the Ri planned to present a series at Easter and another at Whitsun too, but for some reason these fixtures didn’t prove popular, so only theChristmas Lecturesbecame a mainstay. They have been given almost every year, stopping only from 1939 to 1942, during the blitz in World War II when it was too dangerous for children to come into central London.

Michael Faraday – who had left school at 13 himself and was keen to introduce young people to science – personally gave the Lecture series nineteen times. His last series – ‘On the Chemical History of a Candle’ in December 1860 – was published as a book. It has never been out of print since.

The Christmas Lectures usually take the form of between three and six hour-long talks originally delivered on several days over the festive period. The Lecture series has been continuously broadcast on television since the 1966 on various channels (but in parts broadcast since 1936). This year, they will be shown on BBC Four and now Lectures past and present are available towatch onlinethrough the Ri website. After the London Lectures are finished, many of the Lecturers go on tour to entertain international audiences. Faraday would no doubt be astounded to know that the Lectures continue today and reach so many people worldwide.

When I was asked to research the most fascinating speakers of the last century for a new book about Christmas Lectures focussed on the natural world,11 Explorations into Life on Earth, I jumped at the chance. Digging for more details on the Lectures was a real treat, through the Ri archives I was shown transcripts, photographs, artefacts, newspaper reports, handwritten letters and even, occasionally, viewers’ complaints.

As a kid, I remember being glued to the Lectures on television every festive season. Watching at home, I always wished I could be in the audience, to stick up my hand in the hope of being picked to help with a demonstration. The Ri Lecture Theatre has been filled – as I discovered during my research – with a teeming array of furry mammals, luxuriant plants, squawking birds, crawling insects and plenty more besides. Snakes and crocodiles, lion cubs and lemurs, bears, horses, sea spiders, water beetles, plastic grubs and mechanical ducks have all been introduced to awe and educate rapt audiences. Along with those audiences, I always had the sense while watching that I was being let in on some big secrets: science is all around us, it really matters and it can be tremendous fun. This year’s Christmas Lecturer, Professor Sophie Scott (who is interviewed in thelatest issueofBBC Focusmagazine), has expressed the same sentiment.

Early lectures were sometimes difficult to research – transcripts hadn’t always been filed so many of them were identified by an intriguing title alone. By the early twentieth century, studies of the living world were gradually shifting away from a descriptive discipline (preoccupied mainly with finding and naming species) to the modern science of ecology. Instead of studying organisms in isolation, scientists began to consider the ways living creatures interact with each other, and their environment, forming an intricate web of life.

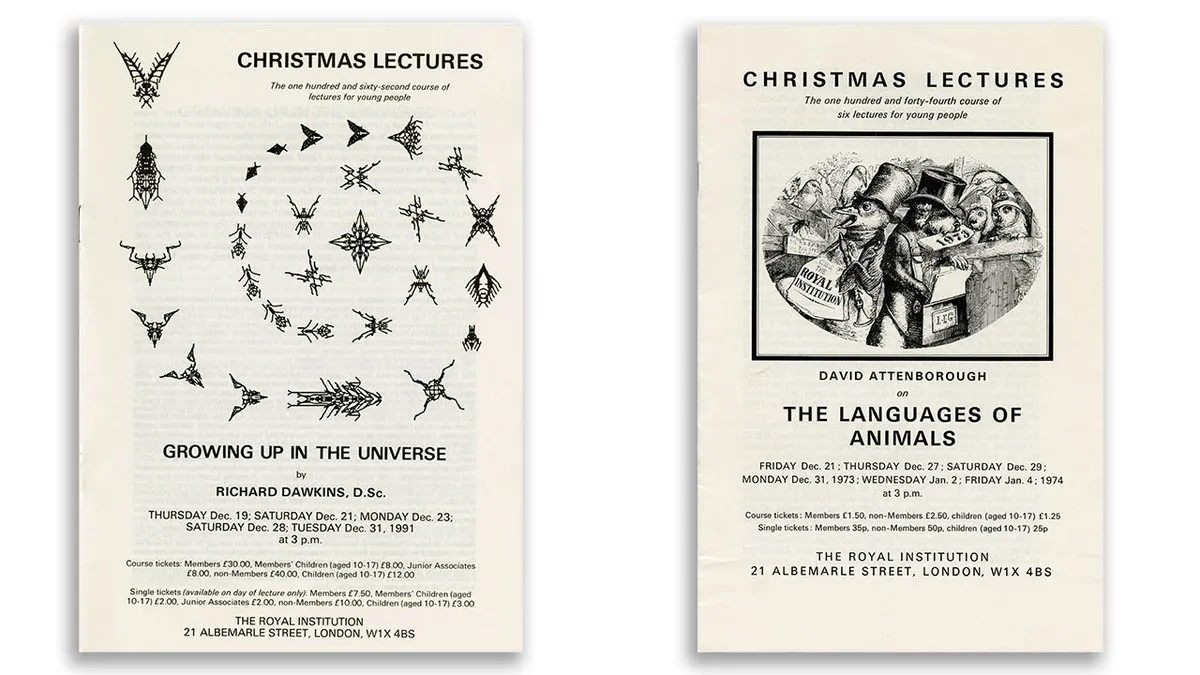

Michael Faraday himself might have been surprised by the topics covered. Since their inception and throughout the nineteenth century, relatively few of the Ri Christmas Lectures have focused on the living world. There was one Lecture in 1831 by the Scottish naturalist James Rennie simply entitled ‘Zoology’ and another, ‘Botany’, by John Lindley in 1833 (but there is very little archive material to provide details of either). Otherwise, the Lectures tended to concentrate on the physical sciences. Even Charles Darwin’s ground-breaking 1859 theory of evolution by natural selection – explaining how life on earth came to be – didn’t feature in any nineteenth-century Lectures. Astonishingly, Richard Dawkins first tackled evolution in the Christmas Lectures in his explosive series of talks in 1991; perhaps the topic was deemed unsuitable and too controversial for young Victorian audiences. Dawkins undertook an experiment mimicking an explosive beetle and aimed a metal cannonball at his own face to make some of his points, rendering his participation especially memorable.

Richard Dawkins - CHRISTMAS LECTURES 1991 - Growing up in the Universe (YouTube/The Royal Institution)

The Lectures from the twentieth century onwards reflect the growing interest over the last century in understanding how the living world works, together with mounting concerns that human actions are damaging the living systems on which we all depend in so many ways.

In his lectures on the Haunts of Life, Scottish naturalist and coral expert, J. Arthur Thomson, discusses the incredible ways in which whales are adapted to their marine habitat. As long ago as 1920 – when commercial whaling for whale-bone and blubber was still in full swing – he used his Lectures to warn of the damage man was doing to the populations of these amazing animals. Sir David Attenborough addressed the same issue in his1973 Lectures on the Languages of Animals, playing a haunting recording of a humpback whale which the audience immediately identified. ‘The humpback whale is becoming increasingly rare and is getting closer and closer to extinction,’ Attenborough lamented, ‘because we human beings kill humpback whales in order to make margarine and soap, which you may well think is a crime and a scandal.’

A few years after Attenborough’s lectures, the Save the Whale campaign was successful in its bid to introduce a global moratorium on whaling. An aspect of the Lectures which surprised and delighted me during the research process was just how ahead of their time many of the early lecturers were, speaking eloquently about issues including conservation that were far from mainstream then.

The lecturers I researched showed their deep devotion, fascination and respect for the living world; dismay at the problems nature faces, but also strong conviction that balance can be restored. Sir Julian Huxley (brother of Aldous) gave his Christmas Lectures in 1937 about endangered wildlife, pulling no punches as he showed a film of baby seals being clubbed for their fur in Canada. He went on to co-found the World Wildlife Fund. Sir David Attenborough – whose charming foreword to my book revealed that he was terrified before his 1973 series that the animals wouldn’t behave as he hoped, and begged to be released from his contract – still campaigns for the natural world and inspires viewers the world over with his programmes.

What all these speakers, and the many others who have graced the stage of the Ri Lecture theatre, had in common was their passion to communicate the wonders of the world and the astonishing creatures that inhabit it to their captivated audiences. I look forward enormously to the next two hundred years of exciting Ri Christmas Lectures!

For more on fascinating past Lectures check out our previous Brain Food book of the week13 Journeys through Space and Time.

The2017 Christmas Lecturesby the Royal Institution, presented by neuroscientist Professor Sophie Scott, will bebroadcast on BBC Fourin late December, produced by Windfall Films.