In the Siberian summer, the Sun never sets. Along the banks of the Kolyma River in the region’s northeast, straggly larch and tall spruce trees preside over a patchwork of lichen and moss. It’s one of the world’s last great wildernesses, but its beauty is being eroded – literally – by an underground business that is booming.

Every year, clandestine crews of men head to the region to look for hidden treasure: the tusks of woolly mammoths that lie frozen in the permafrost. It’s dirty, backbreaking work. They sleep in makeshift tents, live off canned beef, noodles and vodka, and operate illegally, ripping the mammoth remains from the earth with a level of brute force never seen before. They sell the mammoth tusks at great profit, creating a new ‘gold rush’ – not in precious metals, but in body parts.

And amidst it all, concerns are mounting that the practice could have a devastating effect on the mammoth’s modern-day cousin, the African elephant.

The mammoth graveyard

Fifty thousand years ago, Siberia looked very different from how it does today. Instead of forest and scraggy tundra, the region was blanketed in lush grasslands and fertile soils, and herds of woolly mammoths roamed the open plains.

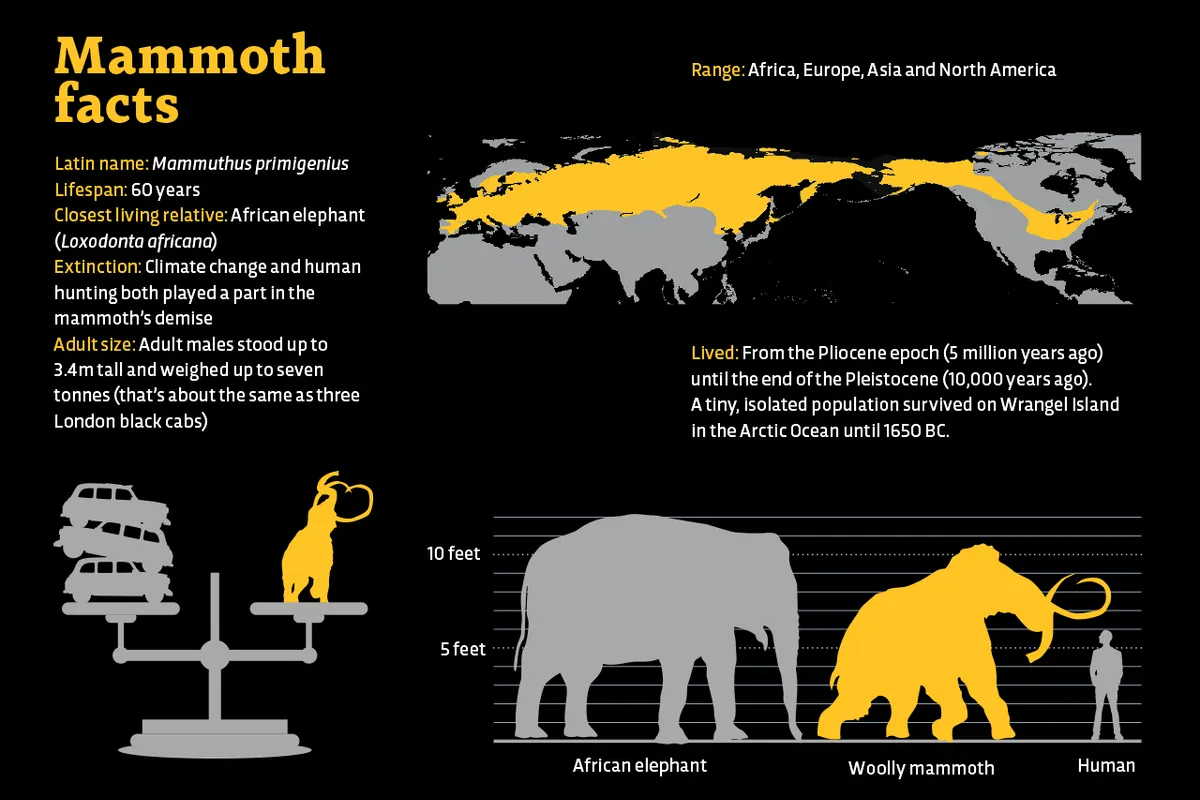

Then little by little, towards the end of the last Ice Age, their numbers started to diminish. No one really understands why. Some blame human hunting, some climate change, others a bit of both. What we do know is that they disappeared from Siberia 10,000 years ago, then from their final hiding place – a northerly island called Wrangel – just 3,700 years ago.

Now Siberia is a massive mammoth graveyard, and it’s estimated that the remains of hundreds of thousands of individual animals lie buried in the permafrost.

Sold down the river

As our world warms, the permafrost is melting and the remains of these fallen giants are starting to surface. Occasionally, tusks can be spotted poking out of landlocked tundra, but more often than not, they are found in places where the permafrost erodes naturally, like river banks and coastlines.

In settlements that turned into ghost towns after the fall of communism, mammoth tusks have offered a lifeline to the region’s indigenous people, who are still legally allowed to collect them. A single tusk can change a man’s life. In rural Siberia, where the average monthly salary is around $500 (£380 approx), a 65kg tusk can net its finder upwards of $30,000 (£22,700 approx). As a result, tales of ‘get rich quick schemes’ have spread, luring a new breed of hunter that arrives by boat.

The clandestine crew

It’s hard to know exactly who these new tusk hunters are, or how many of them are operating. “The mammoth tusk trade is a very difficult theme,” says Semyon Grigoriev, head of the Mammoth Museum at the North-Eastern Federal University in Yakutsk, Siberia. “Most tusk hunters work illegally, so they don’t like public attention.”

While some permits are available for recognised companies, the majority of tuskers work without permits for unspecified middlemen, who then sell on the tusks to the Far East. Grigoriev says. Whereas locals prod the tusks from the tundra with spades and spears, these new hunters work in gangs, raiding the riverbanks with industrial-style equipment that wouldn’t look out of place in a fire station.

Read more about prehistoric animals:

Blast off!

They blast the riverbanks and crumbling permafrost cliffs with jets of water, drawn from the nearby river or sea. Power comes from makeshift petrol-powered water pumps, converted from the engines of snow mobiles and other vehicles. The pressurised cannons reduce the icy permafrost to a slurry of smelly, pebbly sludge, which then oozes back into the waterways.

Any body parts that are liberated come tumbling to the ground. Because the permafrost has remained frozen since the end of the last Ice Age, some 11,700 years ago, the remnants are perfectly preserved. Intact tusks are kept, but everything else – bones, teeth and tusk fragments – are discarded and left to the elements. In the years that follow, these will either wash or weather away.

Unnecessary damage

Sometimes the men gouge out entire hillsides, boring tunnels that stretch for 60m or more into the earth. “This is a new phenomenon in Russia,” says palaeogeneticist Prof Love Dalén from the Swedish Museum of Natural History in Stockholm, who routinely visits Siberia to source remains for his scientific studies.

“Obviously it’s not good, because they’re destroying the permafrost and it leaves big scars.” To maximise their rewards, the tuskers try to find areas where the density of bones is particularly high. This is a source of frustration to Dalén, because these mass graveyards are of special scientific value.

“They’re either a human kill site, or some sort of natural trap where the mammoths have died,” he says.

Science’s loss

The result is that tusks that could be used for scientific research are lost to the ivory trade. In life, a mammoth’s tusks were up to 4m in length, and were used to help forage for grass beneath the snow. Today, they provide a valuable record of the animals’ lives.

As well as containing DNA which can be used for genetic studies, the tusks contain a series of growth rings, much like a tree trunk. From this, researchers can deduce the animal’s age, but also snippets of its life story. The tusks of adult females, for example, grew more slowly during pregnancy, so from tusks it’s possible to tell the number of offspring that were produced.

Buried treasure

So the tuskers bore deeper and deeper, in search of more ivory. Sometimes they create huge underground caves. In 2012, Dalén visited a site with around 30 tunnels. It had been excavated a few years previously when the hunters took the tusks of a baby mammoth they had found.

Dalén and the team wanted to recover the body, but in the repeated thaws of successive summers, the tunnels had become unstable. The one they were in collapsed before they could find the mammoth, moments after the team crawled out of it. “We were five minutes away from losing maybe 12 people,” he says.

Sleeping on the job

No one knows how many tuskers have been injured or killed. Because the operation is illegal, no records are kept. Although the inside of a fresh tunnel is rock hard, there’s a risk inside of low oxygen levels, and outside of landslides around the entrance to the caverns. The most dangerous element, however, isn’t the tunnels but the waterways.

The rocky rivers are murky from the dislodged sediment, and full of driftwood and felled logs. These men crashed their boat at speed near a spot where two prospectors drowned last year. When a 3am rescue mission found them (it’s still daylight at that time), they were passed out in a boat full of waterlogged equipment.

It’s not just tusks

The ends, however, seemingly justify the means. As well as mammoth tusks, the horns of another Ice Age giant, the woolly rhino, are also prized. A 2.4kg rhino horn will earn its finder around $14,000 (£10,600 approx) when it’s sold to an agent who then exports it to southeast Asia.

In Vietnam, the horns are ground into powder and used in traditional medicine, in the erroneous belief they have the power to cure everything from gout to cancer, snakebites and demonic possession. Mammoth tusks, however, meet a different fate.

Ethical ivory?

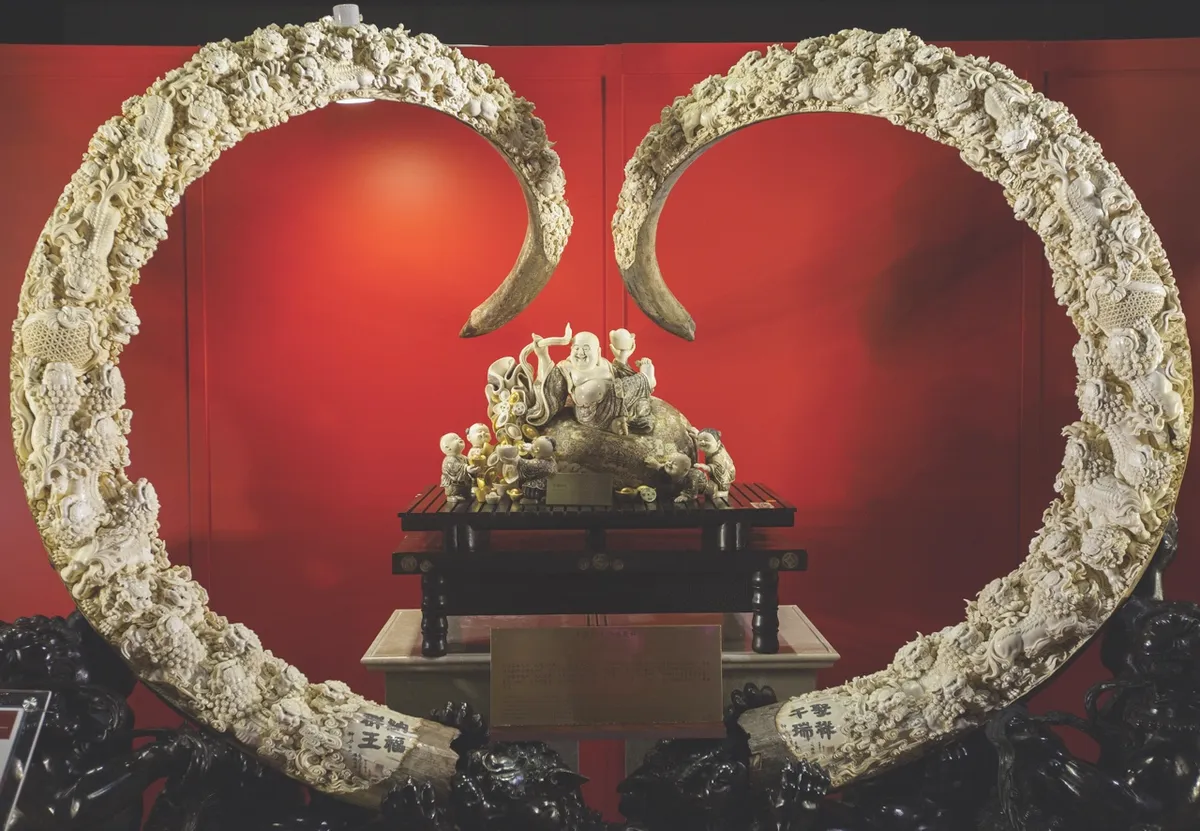

Around 90 per cent of Siberian mammoth tusks – more than 60 tonnes a year – end up in China or Hong Kong, where they are carved into elaborate ornaments. The ultimate status symbol, a carved tusk like this one will cost its owner many hundreds of thousands of dollars. Touted as an ‘ethical’ source of ivory, some argue that mammoth tusks will ease the demand for elephant ivory, but others counter that the existence of ivory in any form only serves to stimulate the market.

It’s a debate that rumbles on, while today, there are just 400,000 African elephants left in the wild. Every year, around 40,000 are killed for their tusks, so the question remains: is it really worth endangering the lives of elephants and tusk hunters for another haul of mammoth ivory, or should we let these sleeping giants lie?

- This is an edited extract from issue 316 ofBBC Focusmagazine –subscribe herefor full features delivered directly to your door or via app.