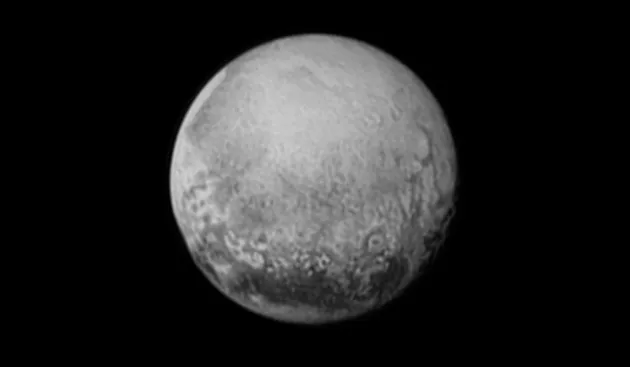

This week, Pluto will give up its secrets. For decades, it has been little more than a pinprick of light lurking in the outer reaches of the Solar System. But now, NASA’s New Horizons space probe is hurtling towards this tiny, frozen world and its strange collection of moons. On 14 July, it will fly by Pluto at a distance of some 13,700 kilometres, mapping its icy surface, sniffing its tenuous atmosphere and scanning its internal structure. A new world will be revealed.

In January 2006, New Horizons embarked on its 9.5-year journey, sailing through the Solar System at over 16km/s. After a brief flirtation with Pluto and its satellite companions, the craft will move on, flying past one or two smaller Kuiper Belt Objects beyond the orbit of Neptune before disappearing into the unfathomable depths of interstellar space. According to Alan Stern, the Principal Investigator of New Horizons, this is a true exploratory mission. “The best we can do is prepare ourselves for the unexpected,” he explains. “We hardly know anything about Pluto. We will learn so much.”

The triangular 480kg craft was built by the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Baltimore, Maryland and Stern’s Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado. It is outfitted with seven instruments, including a high-resolution camera, two spectrometers to study surface and atmospheric composition, two instruments to study fields and particles, a dust counter, and a radio science experiment. A plutonium-powered radioisotope thermoelectric generator provides some 200W of power during the Pluto encounter, while communication with Earth will be maintained by a 2.1m high-gain antenna.

New Horizons’ radio signals will take some 4.5 hours to reach Earth, and because of the huge distance and the relatively low transmitter power, the craft’s data rate will be low. “We’ll receive dozens of photos within a day after closest approach,” explains Stern. “But we’re collecting data a hundred times faster than we are able to transmit them. It will take over a year to send all of it back.” Also, because of the delay, the whole encounter has to be pre-programmed into New Horizons’ onboard computer. “We’ve prepared ourselves for over 250 possible contingencies,” says Stern. “My biggest worry is that something happens that we haven’t thought of.”

The most exciting finds may stem from the study of Pluto’s surface and interior. Like some of the icy satellites of Jupiter and Saturn (notably Europa and Enceladus), Pluto may display some form of ‘ice volcanism’, with active geysers spewing crystals of frozen nitrogen, methane and water into space.

Planetary scientist Bill McKinnon of Washington University in St Louis, Missouri, says he is one of those people who thinks it’s even likely that Pluto possesses an internal ocean, hidden beneath a thick layer of ice.

Everyone knows that water is one of the main requisites for the emergence of life as we know it, the other two being organic molecules and energy. So who knows, if Pluto has a subsurface ocean, it might harbour microorganisms, just as astrobiologists have suggested is the case for Europa and Enceladus. Unfortunately, New Horizons won’t be able to answer that question, so the existence of Plutonian life will remain speculative for many decades to come.

Govert Schilling is an astronomer and science author who has written over 50 books. The full version of this article appears in the Summer 2015 issue of Focus.

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard