The rainbow used to have just 5 colours – until 1704 when Sir Isaac Newton added orange and indigo to the list simply because he had a fondness for the supposedly mystical properties of the number 7.

In fact, there are no pure colours in a rainbow – they all blend into one continuous spectrum - but ever since Newton we’ve settled on 7 and used little rhymes to remember them. Americans favour ‘Roy G Biv’ while British children might learn ‘Richard York gave battle in vain’ – red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo and violet. Attentive children might therefore be perplexed by the song, ‘I can sing a rainbow’, which begins, ‘Red and yellow and pink and green, purple and orange and blue …’

So it would seem that the colours of the rainbow can differ, and when we dip into the cultural histories of these colours, we see even wider differences. In short, how we interpret colours, even how we see them, is more a product of nurture than nature. A few colour-coded stories then:

Red

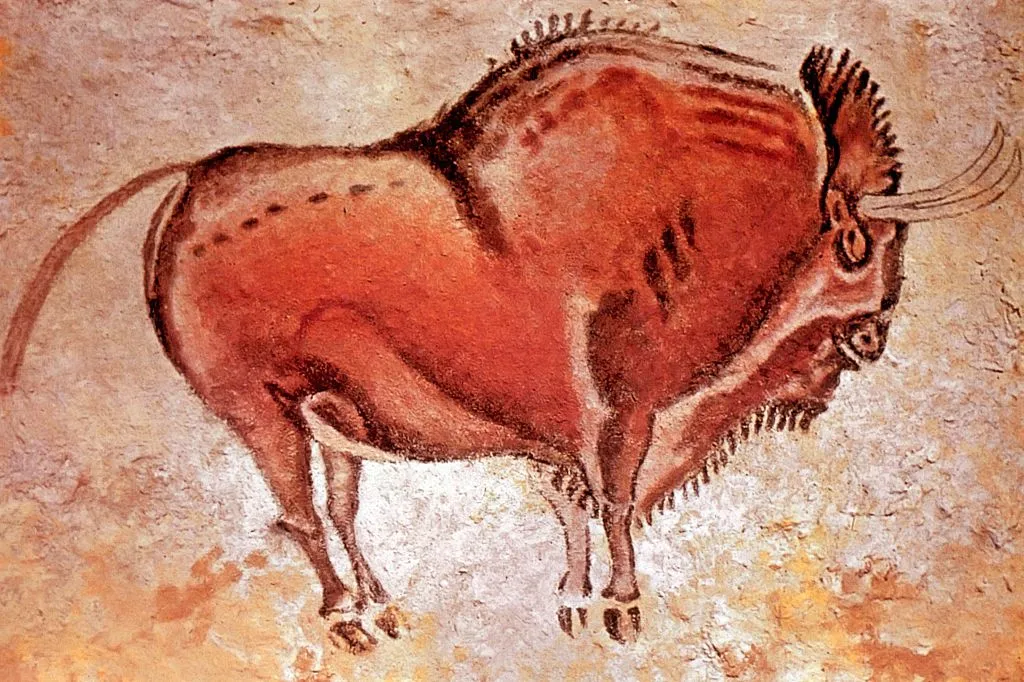

The first colour used in art was red - from ochre. And the first known example of cave art was a red ochre plaque, which contains symbolic engravings of triangles, diamond shapes and lines, dated to 75,000 years ago.

In the same cave – Blombos, in the Western Cape of South Africa – there are suggestions of even older art, including a workshop containing carefully blended paint made from red ochre and marrow fat, along with spatulas and shell mixing dishes.

This paint, thought to be used to adorn bodies and perhaps cave walls, has been dated at 100,000 years ago.

In almost every country red seems to have been the first colour (other than black and white) to be named with its symbolic appeal often drawn from blood, evoking strength, virility and fertility.

Blue

The world’s favourite colour is blue even though it is relatively new to the party linguistically.

The ancient Greeks, Chinese, Japanese and Hebrews did not have a name for blue and thought of it as a version of green. Even today several languages have green-blue blurring, including Korean, Vietnamese, Thai, Kurdish, Zulu and Himba.

Yet blue consistently comes first for both men and women in every country where colour preference has been surveyed.

In one international poll, covering ten countries from four continents, it came out well on top in all of them.

One reason is that it seems to have a calming effect. Students given IQ tests with blue covers had an edge of a few points over those given tests with red covers, perhaps because of the natural connotations of blue – seas, lakes, rivers, skies.

Yellow

Tony Orlando & Dawn - Tie A Yellow Ribbon Round The Ole Oak Tree ) TOTP ) 1973

This most contrary of colours has long been associated with cowardice (yellowish bile was thought to make you peevish) and ever since the 8th Century it was the colour of anti-Semitism. The Caliph in Medina ordered Jews and Christians to wear yellow badges because it was the colour of non-believers, and it spread, via Edward I (yellow patches for Jews) all to Nazi Germany’s yellow stars.

But it is also the colour of defiance in the form of the yellow ribbon, which started with the women’s suffrage movement in Kansas in 1867 (they chose yellow because the sunflower was the state flower).

The 1973 Tony Orlando and Dawn song, Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree gave the defiant version of the yellow ribbon an unexpected revival boost - it was later used in protests in the Philippines, Hong Kong and South Africa.

Green

The usual associations of green relate to the natural world but it has also picked up some more malign connotations, including envy, jealousy, inexperience, illness and poison (at least in comic book bottles).

This last meaning came from the pea-green pigment called Scheele’s green, used in dyes and paints for carpets, fabrics, wallpaper, ballroom gowns and confectionary. Problem was that this dye, invented in 1775, contained high doses of arsenic.

It was particularly lethal in wallpaper, releasing tiny particles of arsenic into the air. When Napoleon died in St Helena in 1821 British were suspected of poisoning him. Later, however, it was discovered that the green wallpaper in his room contained arsenic. This may have hastened his death, but the real cause was bowel cancer and a perforated ulcer.

Despite knowledge of its toxicity it was only in the early 20th Century that manufacturers stopped producing Scheele’s green.

Orange

The only colour in the English language that takes its name from a fruit is orange. It all goes back to China around 4,500 years ago when oranges were first cultivated and travelled west down the Silk Road. They went to Northwest India where the Sanskrit word for an orange tree – narrangah – served as the root for many languages as oranges were planted and sold – Narang in Farsi, naranj in Arabic and naranja in Spanish.

The English word orange is a corruption of the Sanskrit. People mistook ‘a naranga’ for ‘an aranga’, and so it evolved into ‘an orange’.

Before the fruit arrived, the English word for the colour was geoluread (yellow-red) but in the 16th Century orange took over. In some languages, however, the two are separated.

In Afrikaans, for example, the colour is oranje but the fruit is lemoen and several languages, including Himba, Nafana and Piraha, have no word for the colour.

Purple

The first colour to come in synthetic form was purple. In 1856, William Henry Perkin, an 18-year-old chemistry student, was told to conduct an experiment using coal tar to find a cure for malaria. He failed but was intrigued with what happened when he dipped a piece of cloth into his mixture of coal analine and chromic acid: it came out purple and held its colour. He patented the dye he called mauveine and became a rich man after it was mass-produced.

Until then purple had been prohibitively expensive (the ancients needed to crush 12,000 murex sea snails to get on gram of Tyrian purple) but the result of Perkin’s discovery was the ‘Mauve Measles’ as Punch magazine called the fashion craze.

It had a revival in the late 1960s as the colour of the counter-culture and is now seen as a feminine alternative to pink.

Pink

10 years ago evolutionary psychologists from the University of Newcastle-upon-Tyne designed an experiment to test whether pink was an innately feminine colour and blue a masculine colour. It turned out that blue was favoured by both sexes, but that pink had more female support. T

heir results were heralded as ‘proving’ that pink was inherently feminine, but this was thrown into doubt when critics protested that this was a recent development - earlier in the century women’s magazines regularly advised readers to choose pink for boys’ clothes.

For example, in 1918 the British Ladies Home Journal noted: ‘The generally accepted rule is pink for the boy and blue for the girl. The reason is that pink being a more decided stronger colour is more suitable for the boy…’

It was only in the 1950s that pink became a decided feminine colour – through American advertising campaigns.

The Story of Colour: An Exploration of the Hidden Messages of the Spectrum by Gavin Evans is available now (£20, Michael O'Mara Books)