Nothing says ‘get out of the water quickly’ like the sight of a shark’s fin and the pulsing theme tune of theJawsmovie. Sharks are the ocean’s top predator. There are around 500 species, varying in size, diet and behaviour, lurking in waters all over the world.

Their teeth come in all shapes and sizes, from the piercing, needle-like teeth of the goblin shark, to the crushing, flattened teeth of the angel shark, and the slashing razors of the great white. An extinct species of mackerel shark, known as the megalodon, had the biggest teeth of any known shark, with triangular gnashers measuring more than 17cm.

When an adult human loses a tooth, it’s game over and a trip to the dentist is needed to have an implant fitted. Sharks, however, can replace lost teeth throughout their life.

They need to.

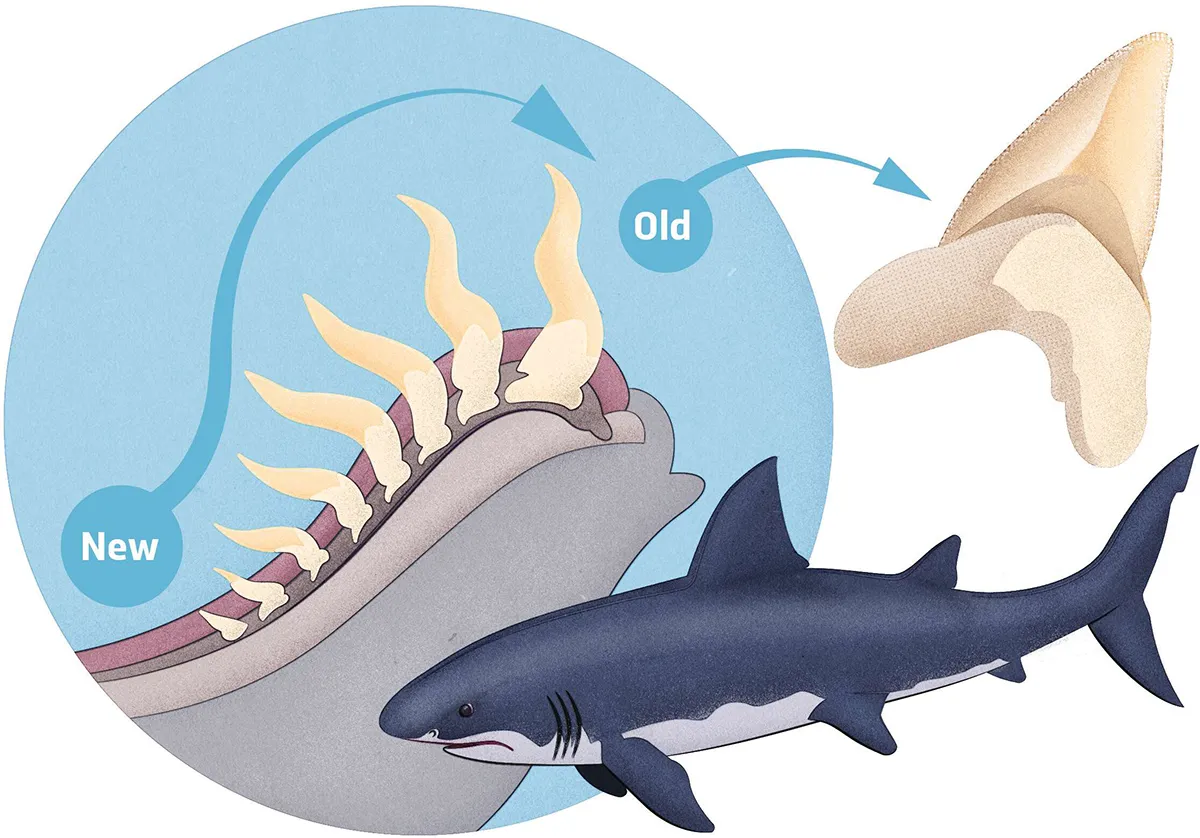

Ground sharks, which are the largest order of sharks, including hammerheads and tiger sharks, lose around 35,000 teeth in a lifetime. They frequently fall out or become damaged when the fish are grappling with their prey, but the sharks are blessed with multiple rows of teeth, which are lined up, one behind the next.

When a tooth falls out, the corresponding tooth in the row behind simply moves forward to take its place. And the one behind that one moves forward to take its place. And so on.

It’s like a conveyor belt that’s made of teeth.

Working with catsharks, scientists have discovered pockets of stem cells inside the sharks’ mouths, which can divide to produce new, more specialised cells, which ultimately form the teeth that are needed to keep the conveyor belt stocked.

The genes controlling this process have similar counterparts in humans, so now scientists are wondering if they could tweak the activity of these genes in people, to help us regrow lost teeth too.

Read more:

- Why can’t we regrow teeth?

- How do sharks smell blood underwater?

- Why do we have wisdom teeth?

- How powerful is a great white shark’s jaw?

Asked by: Sam Simmons, via email

To submit your questions email us at questions@sciencefocus.com (don't forget to include your name and location)