A study using satellite mapping technology has revealed 11 new colonies of emperor penguins living in Antarctica.

The “exciting discovery” means the known population of the birds has swelled by around 5-10 per cent to more than half a million, researchers said.

It has important implications for the future of the species, whose favoured breeding ground is sea ice, which is vulnerable to climate change.

Read more about penguins:

- Penguins help researchers identify the most vulnerable areas of the Antarctic

- Adelie penguins are more successful with less sea ice

- Warming oceans drive almost 60 per cent drop in chinstrap penguin population

Findings published in the journal Remote Sensing In Ecology And Conservation detail how images from the European Commission’s Copernicus Sentinel-2 satellite mission were used to locate the birds, whose remote, freezing habitat makes them difficult to study.

While penguins are too small to appear on images taken by the Sentinel-2 satellite, the researchers were able to locate and track their populations by identifying large brown patches on the ice – stains made by the penguins' droppings, called guano.

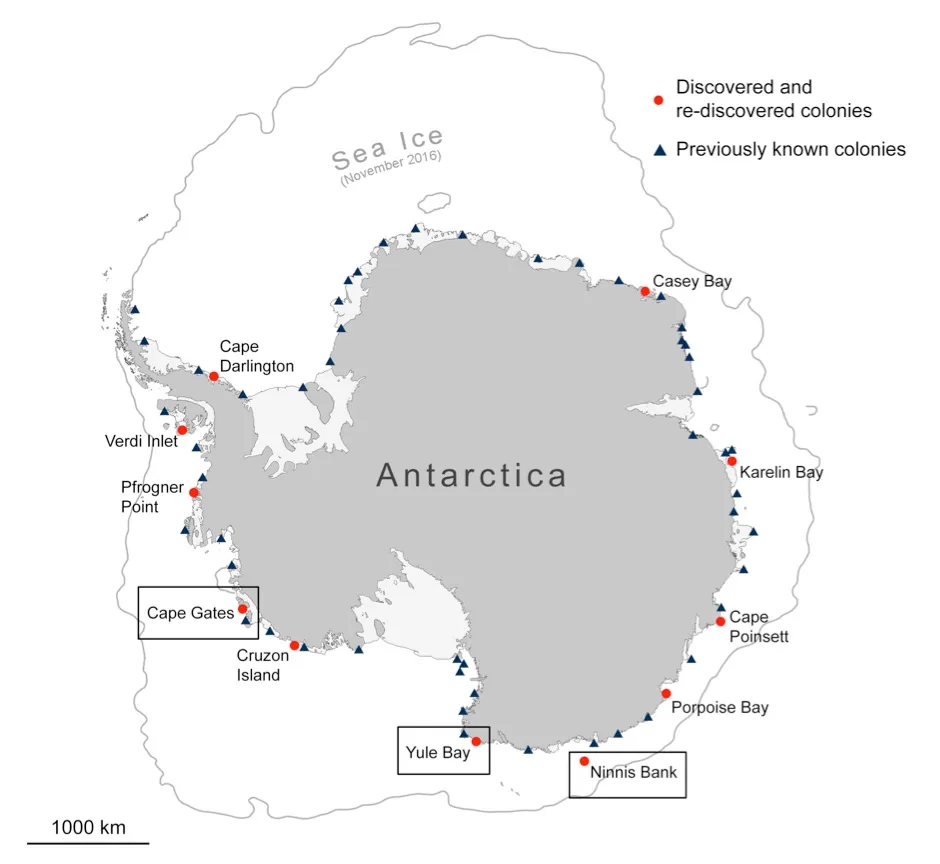

Some 11 new penguin colonies were confirmed, taking the global census to 61 colonies around the continent, to which the species is native, researchers said.

However, the locations of all the newly found colonies are in areas "likely to be highly vulnerable under business‐as‐usual greenhouse gas emissions scenarios, suggesting that population decreases for the species will be greater than previously thought," write the researchers in the paper.

Dr Phil Trathan, head of conservation biology at the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), said: "Whilst it’s good news that we’ve found these new colonies, the breeding sites are all in locations where recent model projections suggest emperors will decline.

"Birds in these sites are therefore probably the ‘canaries in the coalmine’ – we need to watch these sites carefully as climate change will affect this region."

Black and white with yellow ears, emperor penguins are the largest penguin species, weighing up to 40kg and living for around 20 years. Pairs breed in the harshest winter conditions, with the male incubating the eggs.

Last year, scientists raised concerns over Halley Bay, Antarctica’s second biggest breeding ground for emperor penguins, amid low breeding rates there in recent years.

BAS geographer Dr Peter Fretwell said: "This is an exciting discovery.

"The new satellite images of Antarctica’s coastline have enabled us to find these new colonies. And, whilst this is good news, the colonies are small and so only take the overall population count up by 5-10 per cent to just over half a million penguins, or around 265,500-278,500 breeding pairs."

Reader Q&A: How do penguins see clearly underwater?

Asked by: Sam Leech, by email

In our eyes, most of the focussing work is done by the cornea at the front of the eye. The lens only contributes about ten percent, and is just there to fine tune the focus for sharp images at different distances.

When we are underwater though, the difference in refractive index between the surrounding water and the tissue of the cornea is much lower, so a given curvature doesn’t bend light as much. Our eyes are optimised for air and our lenses can’t adjust enough to make up the difference, so our vision is blurry underwater unless we wear goggles.

Fish can see clearly because their corneas are more spherical (a ‘fish-eye lens’) and so can focus more strongly, but this makes fish short-sighted in air. Penguins need to be able to see clearly on both land and underwater, so neither cornea shape will do.

Instead they actually have corneas that are much flatter, even than ours. This takes almost all the focussing power away from the cornea and nearly all the work is done by the lens. To form a sharp image, the penguin’s eye must be able to change the shape of the lens a lot more than the lenses in either fish or human eyes do.

Penguins’ lenses are softer and the muscles can squeeze them up against the opening of the pupil. This makes them bulge outwards in very rounded shape. Diving birds use this technique as well but penguins are the masters.

Read more: