TheGrandfatherParadox

Time travel theory

A time traveller goes back in time and either accidentally or deliberately (if you are in a macabre mood) kills his own grandfather, before the time traveller’s father has been conceived. So the time traveller is never born, so he never goes back in time, so his grandad never dies, so the time traveller is born. And so on.

In the movies

If Marty McFly accidentally prevents his own parents falling in love and marrying, he will not exist. But as the science fiction writer Robert Heinlein put it, “a paradox can be paradoctored.” Marty does change the past, but in a positive way. He comes home to a different, better future than the one he left.

Is it possible?

An idea loved by sci-fi writers, and with some basis in scientific fact, is that all possible realities exist in some sense side by side. These ‘many worlds’ are like the branches of a tree, each with its own version of history. If you went back in time, into the trunk of the tree, and then forward again, you might go ‘back’ up a different branch from the one you came down. You go back in time and stop your parents meeting, then forward in time up the branch in which they never met and you were never born.

There would, though, be one timeline in which the traveller had vanished, never to return (as in HG Wells’s original time travel story, The Time Machine) and another with a person who has no parents. Complicated, but not paradoxical.

The Bootstrap Paradox

Time travel theory

An item or a piece of information is passed from the future to the past, becoming the same item that is passed from the past to the future.

In the movies

In Back To The Future, at the dance in 1955, Marty McFly gets on stage and sings “an oldie” where he comes from: Chuck Berry’s Johnny B. Goode. Chuck’s cousin, Marvin, is present at the dance and holds up a phone so Chuck can listen in. Inspired by the sound, Chuck later releases the song and Marty would then hear it in the future. But who wrote it?

Where did this idea come from?

This theory was popularised in Robert Heinlein’s 1941 short story, By His Bootstraps (hence the paradox's name), where a notebook is found by the main character in the far future. He takes it, then travels to an earlier point in the future and uses the useful translations within the book to help establish himself as a benevolent dictator. When the notebook becomes worn and dog-eared, he copies the information into a fresh notebook and discards the original. Towards the end of the novel, he muses that there were never two notebooks – the new one is the one that was found by him when he arrived. Mindbending!

Polchinski’s Paradox

Time travel theory

If a billiard ball is rolled into the mouth of a wormhole at just the right speed and angle, it will come out the other end just in time to cannon into its younger self and prevent the younger self going into the tunnel.

Is it possible?

This is one theory that is taken very seriously by scientists, and has been discussed in research papers published in respectable journals. Their interest is fired by the fact that there is nothing in General Relativity that forbids time travel, and that closed time-like curves (CTCs), or a path through space-time that ends up back where it started, at the same point in space and time, are allowed.

Is that the full story?

Not exactly, there are also self-consistent CTCs. If the billiard ball is approaching the mouth of the tunnel, its older self can emerge from the second mouth and give its younger self a glancing blow exactly right to send it through the wormhole in such a way that it will emerge to give itself a glancing blow that does the same thing. There are many possible consistent trajectories of this kind. In the most extreme case, the ‘second’ ball emerges from the tunnel and knocks the ‘first’ ball completely away, but in turn it gets deflected into the wormhole, whereit then takes the place of the ‘first’ ball.

A bunch of rather hairy calculations showed that there is never a system like this where there are no self-consistent trajectories, and that in some cases there can be an infinite number of self-consistent solutions to the equations.

All of this lends weight to Russian physicist Igor Novikov’s conjecture, sometimes more grandly referred to as Novikov’s Self-Consistency Principle, which states that time travel is allowed, but paradoxes are forbidden. This could resolve the Grandfather Paradox – if you go back and try to kill your grandfather, something will always go wrong. Take a gun to shoot him, and the bullet will misfire; poison his wine, and someone else will drink it, and so on.

TheTwin Paradox

Time travel theory

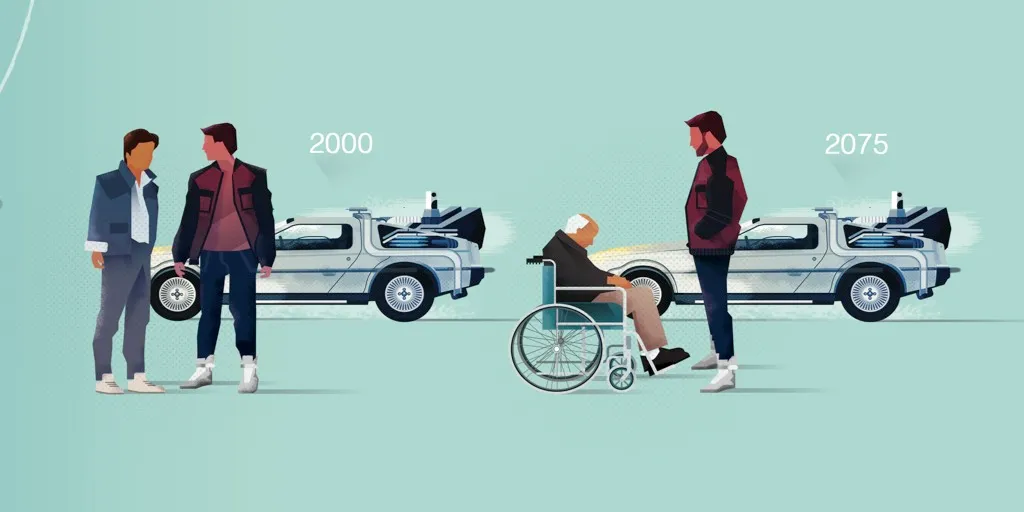

If one member of a pair of twins goes on a journey at a sizeable fraction of the speed of light, he or she will age more slowly than the twin who stayed at home. And when the travelling twin returns home, he or she will be younger than the twin who stayed behind. Literally younger, in biological terms.

In the movies

In Planet of the Apes, astronaut George Taylor, played by Charlton Heston, and his crew spend 18 months in hibernation at near-light speed before landing back on Earth some two thousand years into the future.

Is it possible?

This is the most scientifically sound and least paradoxical of all time travel theories. Special Relativity tells us that moving clocks (including biological clocks) run slow. This has been tested by experiments in accelerators like the Large Hadron Collider. Particles with a known lifetime when stationary in the lab ‘live’ longer when they are moving close to the speed of light.

But hang on...

Special Relativity says that all observers are equivalent, doesn’t it? Why can’t the travelling twin say that they are at rest, while the Earth and the other twin go on a journey into the future? All inertial observers, those in straight lines at constant speed relative to each other, are equivalent. Acceleration changes the rules of the game, and in order to get home the traveller has to decelerate and then accelerate back in the opposite direction.

In the extreme example often used by paradoxers, this turnaround is instantaneous. Cosmologist Hermann Bondi says that if you give each twin a paper bag full of eggs to hold, at the end of the experiment you will find the traveller covered in egg, while the stay at home twin is clean. They are not ‘equivalent’. All of this can be described accurately using equations, and the result is the same.

This kind of time travel is solid science, and it works. One snag: unless you can find a handy wormhole, there is no way to get back from the future. But that is a great idea for a film title…