The name Francis Willughby may not be familiar, but he was one of the seventeenth-century’s greatest naturalists. His studies set the gold standard for all subsequent natural history investigations, and for birds in particular.

Why is Willughby unknown? The answer is partly because he died so young, at 36, just as he was getting into his stride. Another reason is that Willughby’s work was eclipsed by his friend (and ex-Cambridge tutor), John Ray, who after Willughby’s death took it upon himself to ensure that Willugby’s studies were published.

Like Willughby, Ray was clever and highly motivated, and as well as turning Willughby’s notes into three large volumes, the combination of a long life (he lived to the age of 77) during which he published a succession of his own outstanding books (mainly on botany), led subsequent naturalists to assume that Ray had been both the driving force and the brainpower behind his and Willughby’s partnership. Willughby was demoted to a ‘talented amateur’.

Until recently there was little to challenge this view, because Ray’s well-intentioned efforts to consolidate the memory of his friend, resulted — so it was thought — in most of Willughby’s original notebooks and letters to be lost, so there was little evidence to contradict the Ray-as-hero view.

John Ray’s reputation was further enhanced in 1942 through the publication of an influential biography by the Cambridge scholar Canon John Raven, who aligned himself very closely with Ray and downplayed the importance of Francis Willughby. However, when Raven’s book was complete and at the printers, he learned that a hoard of the existence of a hoard of Willughby memorabilia in the family archive. Too late to change anything — and I’m not convinced he would have done so anyway — all Raven could do was to add a note to the proofs saying ‘Some day a book will be written about him’ [Willughby]. As a measure of just what he had missed, after Raven was finally shown the hoard by one of Willughby’s descendants, he wrote to tell him that it had been one of the most exciting days of his life.

It was this previously untouched hoard of Willughby memorabilia that I started to investigate some ten years ago. And what a hoard! During his various travels, both in Britain and abroad, Francis Willughby accumulated a vast treasure-trove of paintings, books, insects,birdsand fossils ready to be interrogated and transformed into a huge natural history book.

His early death prevented this from happening, but before that he and Ray had already decided to divide the work up into three volumes on: birds, fish and insects, respectively.

Francis Willughby and John Ray were at Trinity College Cambridge in the 1650s soon after the end of the English Civil War when a great sense of change was in the air, and no more so than in science. Cambridge (and Oxford) scholars were no longer satisfied with the idea that the ancient Greeks had discovered everything there was to know about the natural world and that there was nothing new to find out. As Francis Bacon had pointed out earlier in the century, the discovery of North America with its entirely new fauna a flora provided very clear evidence that there was plenty new to discover. A fresh approach was needed, an approach aptly summed up by the motto of the recently formed Royal Society —Nullius in veraba: Take nobody’s word for it.

Referred to as ‘the new philosophy’ this was the start of the scientific revolution, and while scholars like Isaac Newton focused on mathematics and astronomy, Francis Willughby together with John Ray pioneered a new approach to natural history.

It was while returning from a fact-finding journey in Wales in the early summer of 1662 that Willughby and Ray decided that natural history needed an overhaul. The previous century’s natural history experts, authors like Conrad Gesner and Ulysses Aldrovandi, produced massive, unwieldy volumes, stuffed with huge amounts of largely irrelevant information, at a time when the demonstration of such copious knowledge passed as scholarship. What Willughby and Ray planned were books exclusively on natural history uncluttered by ‘hieroglyphs, pandects and emblematics’.

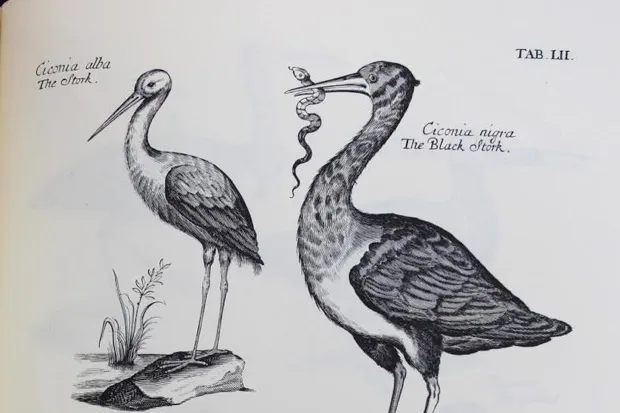

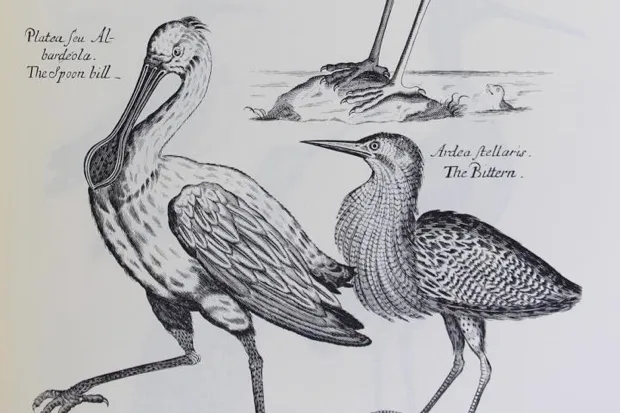

They started with birds, and subsequent ornithologists have acknowledged that theirs is the first truly scientific encyclopedia of birds. It is difficult to underestimate what enormous labour this work entailed. Willughby and Ray’s goal was to see, describe and dissect every known bird — assumed to be about 500 at that time (in fact, we now know that there are around 10,000 species of birds in the world). Their second aim was to use these descriptions to construct a biologically meaningful classification of birds. Classification, of anything, and Willughby like classifying things as diverse as games and words, imposed an order on knowledge that was the starting point for all subsequent research. The efficacy of Willughby and Ray’s classification of birds was obvious to Carl Linnaeus who, a century later used it more or less unchanged in his ownSystem Naturae.

Apart from his impact on ornithology, for me one of the things that made Francis Willughby such an attractive subject for a biography was that he was clearly a thoroughly nice man. Despite his privileged upbringing and obvious intellect Willugby was humble and committed to making his own way in life rather than relying on his family’s standing and wealth. In his role as sheriff, he was supposed not to tolerate beggars or vagabonds, but, as his daughter recounted, if he knew one was coming to the house seeking food or alms, Willughby deliberately failed to see them, to avoid having to take any kind of action. Francis was a loving husband and father of three children, and verything we know about him suggests that he was charming, modest and fair in all his endeavors.

Willughby died before his bird book could be completed, and Ray, who was then living as part of the Willughby household, took it up on himself to complete it. The book was published, first in Latin in 1676, and then in English in 1678, under the titleThe Ornithology of Francis Willughbyby John Ray. The book’s title was supposed, we suppose, to celebrate Francis Willughby but instead, over the years it was increasingly thought to promote Ray at Willughby’s expense. This view was reinforced when John Ray eventually published his and Willughby’s work on fishes (1686) and insects (1710). The insect volume, which was actually completed by members of the Royal Society after John Ray’s death, identified Ray as the author, with no mention of Francis Willughby, much to the distress of Willughby’s widow and children.

My aim inThe Wonderful Mr Willughbyis to set the record straight. Using the considerable amount of previously unexamined memorabilia I have been able to provide a richer, much more fascinating and better-informed assessment of Willughby’s contribution to natural history. The focus is on birds because this was the subject of Willughby’s first volume; because that’s where my own expertise lies; and because it is with birds that the novelty of Willughby and Ray’s classification was first apparent. We know more now about the biology of birds than any other group of animals, and it was Willughby’s book that got ornithology off to a flying start, and crucially, on a sound, scientific basis.The Wonderful Mr Willughbyis the story of the man that began the scientific study of birds.