When 16th century seafarers stumbled across Mauritius, nestling in the midst of the Indian Ocean, they found themselves in an island paradise. Turquoise waters, white sands, and tropical forests. Fish so plentiful they could be netted with ease, birds so abundant they could be swatted from the sky, and giant tortoises so compliant, they could be ridden along the beach.

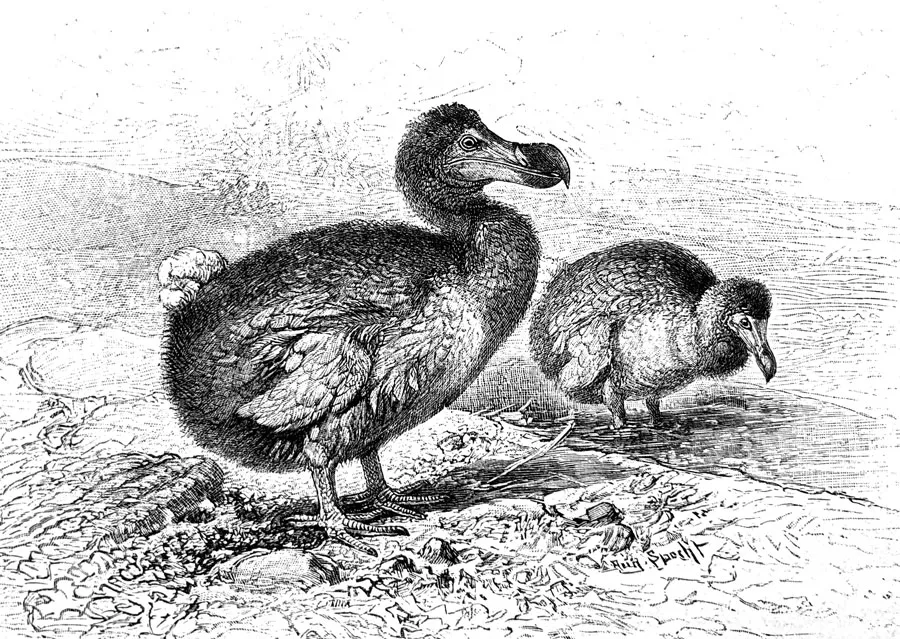

Amongst them all, was the dodo; a large, ludicrous-looking, fat, flightless pigeon that had evolved without predators. It had no fear of the sailors, who walked right up to it, clubbed it round the head, and then cooked it in a stew.

Settlers later brought rats, pigs and other non-native species, which competed with the dodo, and ate its chicks. Less than a hundred years later, the dodo was extinct.

The blood of the dodo is on our hands, but as biotechnology advances, we may have an opportunity for some sort of redress.

Hot on the heels of efforts to resurrect both the woolly mammoth and the thylacine, American biotech company, Colossal Biosciences, has announced plans to de-extinct the dodo. So, to dodo or not to dodo, that is the question.

How scientists plan to de-extinct the dodo

In 2022, ancient DNA expert Beth Shapiro, who is a scientific advisor to the company, announced that she had decoded the dodo’s full genetic sequence or ‘genome'.

To make a dodo, or something that approximates it, scientists will need to line this sequence up against that of the dodo’s closest living relative, the Nicobar pigeon, and then play ‘spot the difference'.

The dodo-specific sequences will then be edited into specific cells from the Nicobar pigeon. Working in tissue culture, the Nicobar pigeon’s DNA will be progressively tweaked so that it comes to resemble that of the dodo.

Let’s stop here for a moment, and talk about the Nicobar pigeon. With its dark, iridescent plumage, it is the most sultry and stunning-looking pigeon you will ever see.

It’s also hunted for the pet and food trades, and threatened by habitat loss. Numbers are declining. Captive birds could be used as a source of the cells, but it’s presumptuous to assume that we automatically have the right to use them.

Scientists would now, in theory, have cells that contain dodo DNA. Cloning doesn’t work for birds, so it’s not an option. So, the next stage hinges on the nature of these cells. The plan is to use primordial germ cells (PGCs), which come from embryonic birds, and have the ability to generate eggs and sperm.

Once edited, the Nicobar pigeon PGCs will make dodo egg and sperm. The next part of the process will be to implant these cells into an embryonic chicken – yes, I did say chicken – and wait for it to grow up. Depending on its sex, the adult chickens will produce either dodo sperm or dodo eggs, so when two chickens like this mate, the result could be a dodo. A female chicken could actually lay a dodo egg.

Read more:

- What is the dodo’s closest living relative?

- Scientists could create a genetic doppelgänger of a Tasmanian Tiger?

The hidden problems of bringing back the dodo

The technology is still very much in its infancy, but perhaps the biggest hurdle will come after the first egg is laid. Although a chicken might brood a dodo egg, would it know how to raise a dodo chick?

Modern pigeons produce a fatty, protein-rich paste in their crops, which they feed to their newly-hatched offspring. There’s every reason to assume that dodos did something similar, so how to ensure that the new juvenile is properly fed?

The plan, ultimately, is to reintroduce these dodos back to Mauritius, but is there habitat for them? Since the dodo’s extinction, in the late 1600s, the island has lost more than 60 per centof its native forest cover. The invasive species that decimated it the first time around are still there, so either the invaders will have to go, or the dodos would need to be contained within predator-free enclosures.

Even after all this effort, the recovered species still wouldn’t be a dodo. Unavoidable genetic differences between it and the original will make it a proxy rather than an identical copy. So, what’s the point?

One reason is that these lookalikes could be ecologically valuable. When species go extinct, the services they once provided to their ecosystem, such as dispersing seeds or grazing, disappear too. Although the dodo’s ecosystem has changed in its absence, its return could still prove useful. The only problem is that we don’t know exactly how it fitted into its ecosystem because the dodo went extinct before it could be studied.

A second reason focuses, not on the dodo, but on living birds. If scientists can work out how to have one bird species lay the eggs of another, the method could be applied to conservation. But if it sounds far-fetched, there’s already a precedent. Sperm from the threatened houbara bustard have been grown inside chickens, and used to generate live houbara chicks.

Scientists estimate that half of the world’s bird species are in decline. Despite intense efforts to reverse the trend, new conservation strategies have never been more needed.

If Colossal Biosciences can persuade chickens to lay dodo eggs, the knowledge that will be generated could help to save endangered avian species. It’s a bold idea, but it’s one that I believe is at least worth considering.

Read more: