This past summer, an orca named Tahlequah captured the world’s attention. For 17 days, beginning late July, the young animal pushed the lifeless body of her female calf hundreds of kilometres through the Salish Sea, the shared US and Canadian waters of the Pacific Northwest. Labeled J35 by researchers, she is one of just 74 animals that make up the region’s endangered “southern resident killer whales.”

The show of grief wasn’t unprecedented for those familiar with whales, dolphins and porpoises, collectively known as cetaceans. Over the years, scientists have witnessed several species of dolphins refuse to relinquish dead calves, engaging in behavior that strikes most observers as mourning.

In the Pacific Northwest, whale-watching companies and orca enthusiasts regularly celebrate the enduring matrilineal bonds that structure the three southern resident orca pods, noting that male as well as female orcas remain with their mothers their entire lives. Yet for many outside the region, the images of a young mother seemingly grieving the loss of her infant made Tahlequah’s behavior endearingly “human”.

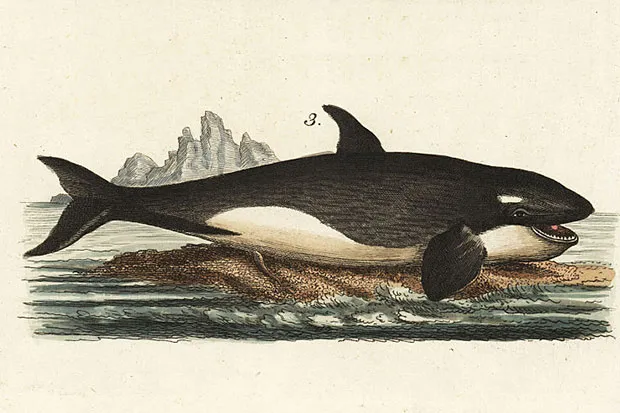

It was a sharp contrast to earlier views of Orcinus orca.

Making the monster

Through the early post-World War II years, people around the globe perceived killer whales as bloodthirsty vermin without meaningful social bonds. At times, shared contempt for the species helped strengthen alliances in the North Atlantic. In September 1954, for example, US soldiers based at the Keflavik Naval Air Station killed hundreds of orcas at the request of the Icelandic government, which believed the predators were damaging local fisheries.

“The scene of destruction was terrible,” wrote a Time magazine reporter, who implied that the “killers” lived up to their reputation by attacking one another in the chaos. “As one was wounded,” he claimed, “the others would set upon it and tear it to pieces with their jagged teeth.” He was wrong. Far from eating one another, the orcas were almost surely trying to raise injured family members to the surface.

Scientists in Japan had observed such behavior firsthand. From the late 1940s to the late 1950s, Japanese whalers harvested 567 killer whales, mostly in the Sea of Okhotsk. In 1958, two Japanese scientists highlighted the social ties that made it possible to take so many of the fast-swimming species.

“In spite of their fierceness, killer whales [have] an ardent passion for their comrades,” they noted. “When a member of their group is killed, it is possible to catch others without moving the catcher boat far away from the place [where] the first one was killed.”

Yet the image of orcas as fearsome monsters continued to circulate. In September 1958 in Malibu, California, reports of killer whales nearby drove thousands of surfers and swimmers from the water. As one lifeguard explained, the “killers” had a “reputation of attacking everything—even boats.” The US Navy diving manual echoed such views, describing orcas as “ruthless and ferocious” and instructing divers to “get out of the water immediately” if one was sighted. In this frightening picture, there was little room for a creature with close family bonds.

Killer whales in captivity

The change came with captivity. In the summer of 1965, Canadian fishermen accidentally caught a large male orca behind their nets off northern Vancouver Island. They sold him to American entrepreneur Ted Griffin, who dubbed the animal “Namu” and transported him in a floating pen south to his Seattle Marine Aquarium.

Namu changed the minds of millions, and it all began with his family. Reporters noted that an adult female orca and two youngsters frequently visited Namu at his net and then followed the pen as it made its way south. At the time, observers interpreted the grouping as a nuclear family with Namu as the patriarch. “It’s fantastic - the warmest, friendliest scene I’ve ever seen,” exclaimed a radio host describing the scene. “Mama and the two babies are out there, not eight or 10 feet from the boat, cheeping at Namu, having a wonderful time.”

We now know that the three whales were likely his mother and two younger siblings, and they probably weren’t having a good time. Yet the assumption of a nuclear orca family nonetheless framed the species in a more relatable light.

In the following months, Griffin and Namu shocked the world, becoming the first human and orca to swim together and then perform in choreographed shows. Not only did killer whales have relations of their own, but it seemed they might form bonds with people. It was a brave new world, and Griffin began catching orcas for other oceanariums. Among them was a young female sold to the new SeaWorld marine park in San Diego. She was dubbed “She-Namu”—or, “Shamu,” and she gave many their first close-up glimpse of a killer whale.

In the realm of human politics, however, no orca could match the impact of Skana. First displayed at a boat show in Vancouver, BC, she helped reveal at the acoustic dimension of orca bonds. In March 1967, handlers arranged a phone call between Skana and two podmates held at Griffin’s aquarium in Seattle. As her relatives’ calls came through the scratchy receiver, the young whale excitedly chirped her responses. Broadcast on a Vancouver radio station, the exchange cast the species in a new light for listeners, who could now imagine orcas’ relationships with one another for the first time. “Once they started ‘talking,’” recalled Griffin, “it brought tears to my eyes.”

The following year, Skana stunned staffers at the Vancouver Aquarium with a display of interspecies empathy. In March 1968, a Pacific white-sided dolphin named Splasher was injured in the tank, perhaps in a game of tag he often played with Skana. At first, he seemed to recover, but days later trainers found him dead at the bottom of the pool. Although Splasher had died of internal injuries, his body had light tooth marks from Skana. The implications were stunning: during the night, when Splasher became too weak to swim to the surface, Skana had grasped him gently and attempted to raise him. As the aquarium director noted at the time, “This is very unusual for a predator animal to do for one of its natural victims.”

Hunting for answers

Soon after, Skana’s interactions with Paul Spong, a young researcher from New Zealand, caused him to reevaluate his priorities as a scientist. Over the following years, he went on to become a pioneer in wild killer whale research. In 1974, he brought Greenpeace leader Bob Hunter to the Vancouver Aquarium to meet Skana, and soon after the two men launch the organization’s first anti-whaling campaign. Footage of the activists confronting Soviet whalers off the California coast in the summer of 1975 riveted viewers around the world. Yet few realized the expedition had its roots in the shifting human view of killer whales and their social ties.

The issue came full circle in 1980, when Soviet delegates to the International Whaling Commission (IWC) reported that their whaling fleet had killed 916 orcas off Antarctica in the previous season, among them 141 pregnant females. For researchers in the Pacific Northwest who had begun to trace the multigenerational matrilines of local orca pods, the slaughter was difficult to fathom. And once again, it seemed that close family ties made orcas vulnerable. “If a killer whale was harpooned,” explained one Soviet researcher, “the group did not leave the wounded animal for a long time. Instead, they stayed to help wounded companions and were often struck down as well.

In the following years, the IWC banned the commercial harvest of cetaceans, and researchers in the Northwest and around the world continued to learn more about the lifelong connections that structure distinct killer whale cultures around the world. Long before Tahlequah’s vigil, then, researchers and environmentalists acknowledged that orcas care for one another, and that mothers have lifelong bonds with their offspring.

But that won’t be enough to save them. In the Pacific Northwest, the southern resident killer whales - the most studied and politically influential cetaceans in history - are at their lowest numbers in 40 years. With growing marine noise, rising toxin levels, and dropping runs of Chinook salmon, their primary prey, these icons of the Pacific Coast seem on their way to extinction. And as recent research has revealed, persistent levels of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in the ocean may result in a worldwide collapse of orca populations in the coming decades.

We have come to understand how much orcas care for one another. Now the question is: Do we care enough to save them?

Orca: How We Came to Know and Love the Ocean's Greatest Predator by Jason Colby is out now (£20, Oxford University Press)

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard