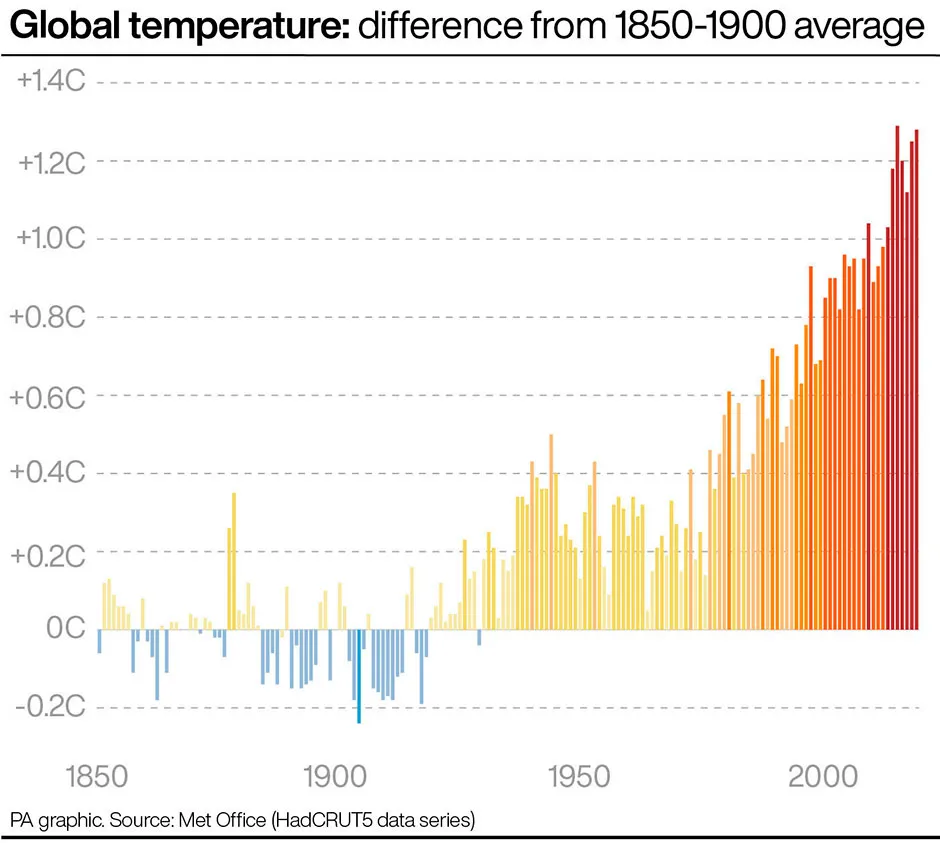

Last year rivalled 2016 for the warmest on record, as global temperatures were measured to be nearly 1.3°C hotter than pre-industrial times, scientists have said.

Analysis of international data by the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) found that 2020 was one of the three warmest years on record, with the trio all falling within the last decade.

Data from the Met Office, University of East Anglia (UEA) and the UK National Centre for Atmospheric Science said 2020 was the second hottest year on record, averaging around 1.28°C above levels seen in the second half of the 19th Century. This is just a fraction of a degree below the record year of 2016, when they were 1.29°C above pre-industrial levels.

United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres said the WMO findings represented “yet another stark reminder of the relentless pace of climate change, which is destroying lives and livelihoods across our planet”.

It came following a 12-month period which saw wildfires in America and Australia ravaging through vast swathes of natural habitat, while cyclones, floods and storms battered communities across the planet.

Read more about climate change:

- Rewilding: Can it save our wildlife and temper climate change?

- Meet the scientists going to extreme lengths to study climate change

The UK felt the effects of Storm Ciara and Storm Alex, which caused flooding and power cuts as record amounts of rain fell, while temperatures reached in excess of 30°C for several days during the height of summer, all considered to be a consequence of climate change.

The WMO report said it was “remarkable” that temperatures in 2020 were virtually on a par with 2016.This was despite the presence last year of the naturally occurring climate cooling phenomenon known as La Niña.

“We are headed for a catastrophic temperature rise of three to 5°C this century," said Guterres.“Making peace with nature is the defining task of the 21st Century. It must be the top priority for everyone, everywhere.”

Under the international Paris Agreement, countries have pledged to limit warming to 2°C above pre-industrial levels, and to pursue efforts to keep temperature rises to 1.5°C to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

The hottest year on record, 2016, saw a strong El Niño, the opposite phenomenon, which boosts temperatures on top of human-caused global warming.

In 2020 there was notable regional warmth in northern Asia, stretching up into the Arctic, parts of eastern Europe and Central America.

“2020 has proved to be another notable year in the global climate record," said Dr Colin Morice, senior scientist in the Met Office’s climate monitoring team.“For the global average temperature in 2020 to be yet another warm year, the second warmest on record even when influenced by a slight La Niña, is a sign of the continued impact of human-induced climate change on our global climate.

“With all datasets showing a continued rise in global average temperature, the latest figures take the world one step closer to the limits stipulated by the Paris Agreement.”

Reader Q&A: Do we really know what climate change will do to our planet?

Asked by: Jennifer Cowsill, via email

There is no doubt that greenhouse gas emissions caused by humans are changing our climate, resulting in a progressive rise in global average temperatures. The scientific consensus on this is comparable to the scientific consensus that smoking causes lung cancer.

Our climate is a hugely intricate system of interlinking processes, so forecasting exactly how this temperature increase will play out across the globe is a complex task. Scientists base their predictions on powerful computer models that combine our understanding of climatic processes with past climate data.

Many large-scale trends can now be calculated with a high degree of certainty: for instance, warmer temperatures will cause seawater to expand and glaciers to melt, resulting in higher sea levels and flooding. More localised predictions are often subject to greater uncertainty.

Read more: