A 4,000-year-old beetle species never known to have existed in the UK has been found in the collections of London's Natural History Museum.

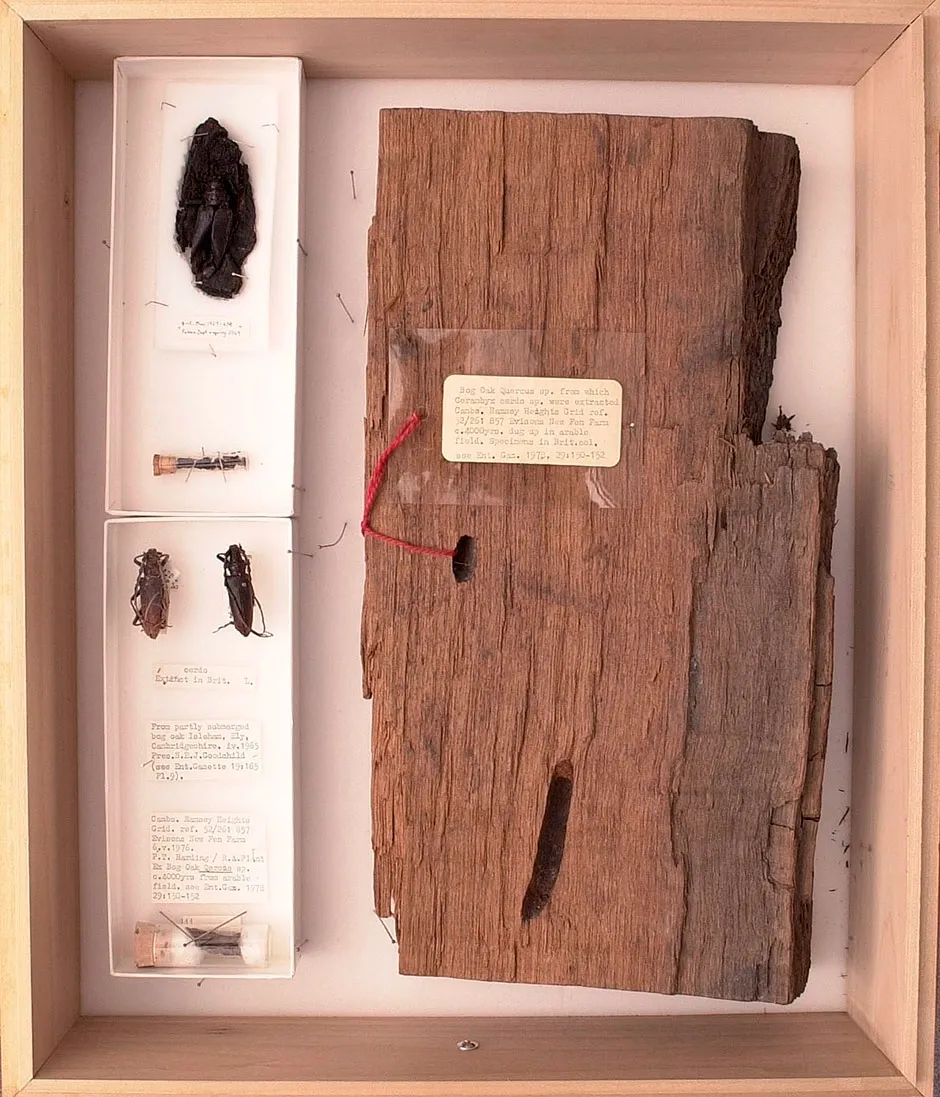

Scientists at the museum have re-examined two specimens of perfectly preserved beetles which were donated to the museum in the 1970s after being unearthed in East Anglia.

The 7.6cm (3in) long Oak Capricorn beetles (Cerambyx) were first found by a local farmer inside a piece of ancient oak wood submerged in a peat bog.The bugs were in good condition and had long, threadlike curved antennae.

“These beetles are older than the Tudors, older than the Roman occupation of Britain, even older than the Roman empire," said Max Barclay, senior curator of insects at the Natural History Museum, who identified the species. "These beetles were alive and chewing the inside of that piece of wood when the pharaohs were building the pyramids in Egypt. It is tremendously exciting.”

The researchers used radiocarbon dating techniques to find out the age of the beetles, which revealed the creatures to be 3,785 years old.

Read more about beetles:

- Source of near-indestructible beetle’s toughness discovered

- Jewel beetles’ shimmering wings are actually a form of camouflage

Barclay believes the Oak Capricorn beetles – which can be found today in southern and central Europe – may have once been endemic to the British Isles but later became extinct due to climate change.

“This is a beetle that is associated with warmer climates, and possibly it existed in Britain 4,000 years ago because the climate was warmer, and as the climate cooled and the habitats destroyed, it became extinct,” he said.

With global warming on the horizon, there are indications that Oak Capricorn beetles could return to Britain in the future, Barclay said.

“It is quite extraordinary to hold something in your hand that looks like it was collected yesterday but is actually several millennia old and can provide new insight into the weather and forest conditions in the late Bronze Age," he said.

“This pair of beetles provide a window into the ancient past and the changes climate change holds for the future.”

Details of the discovery will be revealed in the next episode of the Channel 5 series Natural History Museum: World Of Wonder, which airs on Thursday 28 January at 8pm.

Could a bug crawl into one of my orifices at night?

Let’s put your mind to rest about one thing: there is no evidence that we swallow an average of eight spiders a year. Or any other number for that matter. Spiders are generally quite timid creatures and tend to avoid vibrations (from breathing and snoring) and warm, moist environments. Furthermore, this is a completely unverifiable statistic: if you swallowed something whole, in your sleep, how would you ever know?

That’s the good news. The bad news is that every orifice other than the mouth is fair game. In 2017, a doctor removed a live cockroach from deep in the sinus cavity of a woman in Chennai, India. Leeches can also work their way into the nose, rectum, urethra and vagina. Endoscopy procedures have also found ants, ladybirds and wasps in the rectum.

But the real hotspot for creepy-crawlies is the ears. There are numerous reports of cockroaches, spiders, moths and even an assassin bug being removed from the ears of patients complaining of persistent buzzing sounds. Earwigs probably get their name from the distinctive shape of their hindwings, rather than their preferred habitat. But like many insects, they do occasionally climb into the ear – probably attracted by tasty deposits of earwax.

Rest assured, though, having a creepy-crawly enter your body is extremely rare – especially in the UK – and doctors have always been able to remove the beasties without any serious medical complications.

Read more: