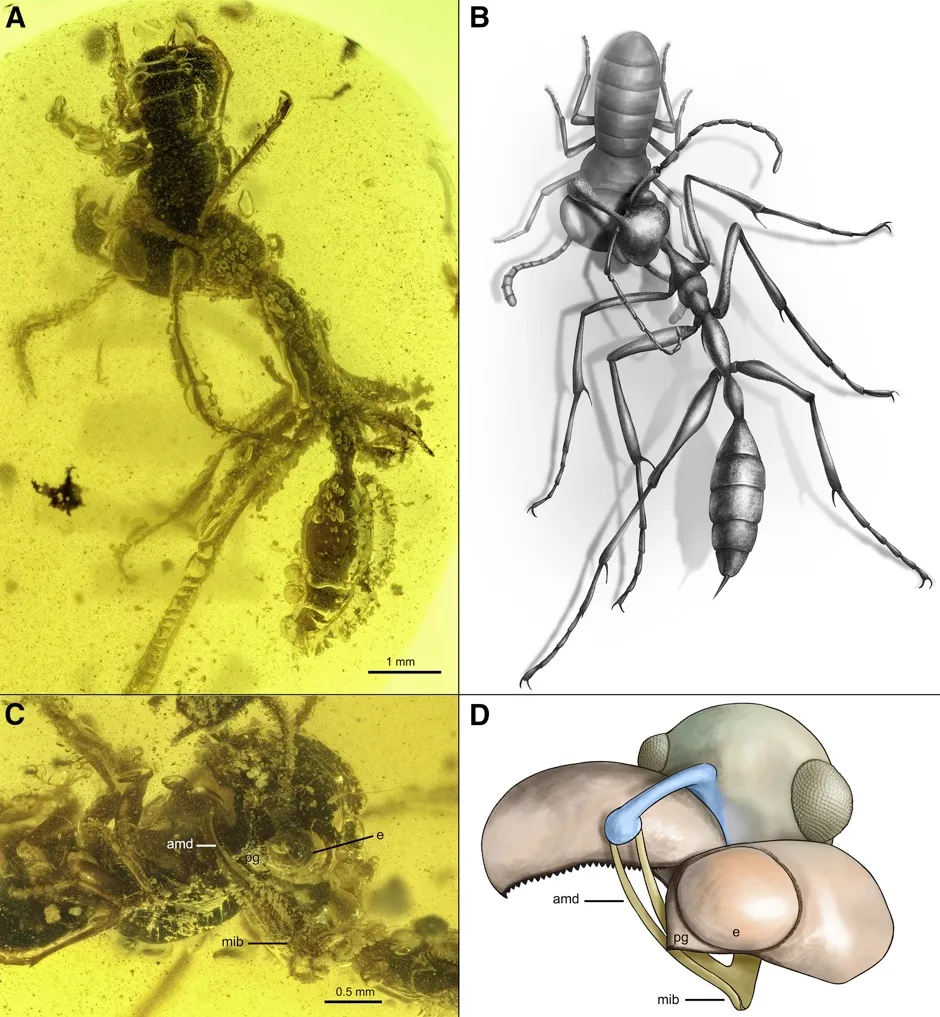

A stunning, 99-million-year-old fossil has captured a hell ant in the act of attacking its prey.

It provides rare evidence for how these extinct insects hunted with their scythe-like mandibles and horn-like headgear.

The hell ant belongs to a previously identified species called Ceratomyrmex ellenbergeri. It was preserved in amber found in Myanmar (formerly Burma) along with its insect prey, an extinct relative of the cockroach.

Read more fossil findings:

- Mystery solved: 240-million-year-old reptile with 'extraordinarily long neck' lived in the ocean

- Skull of hummingbird-sized dinosaur found preserved in amber

- 200 million-year-old fossil shows dinosaur 'walked like a guineafowl'

Like other species of hell ant, Ceratomyrmex sports a pair of deadly mandibles that snap upwards in a vertical motion, unlike the mandibles of modern ants, which move horizontally. Also unlike modern ants, the hell ants have horns protruding from their heads.

The new fossil provides direct evidence that hell ants, which are believed to have become extinct along with the dinosaurs some 65 million years ago, used their headgear to hunt, snapping their mandibles to pin their prey against the horn.

“To see an extinct predator caught in the act of capturing its prey is invaluable,” said study leader Dr Phillip Barden at New Jersey Institute of Technology in the US.

“This fossilised predation confirms our hypothesis for how hell ant mouthparts worked.

“The only way for prey to be captured in such an arrangement is for the ant mouthparts to move up and downward in a direction unlike that of all living ants and nearly all insects.”

Barden’s team thinks that the early ancestors of hell ants would have first gained the ability to move their mouthparts vertically, while the diverse horns evolved later.

Some hell ant species had horns with serrated teeth, while one species is believed to have impaled its victims on a horn that was reinforced with metal.

The team now hopes to find more ancient ant fossils, with the aim of understanding why hell ants went extinct, while their modern-day equivalents thrived.

Reader Q&A: Could we bring back an extinct species using DNA, Jurassic Park style?

Asked by:Alec Maddocks, via email

To ‘de-extinct’ an animal, you need a source of the animal’s DNA, which provides the blueprint for making it. DNA is sometimes preserved in fossils, and the oldest DNA extracted to date comes from a 700,000-year-old horse bone found in the Canadian permafrost.

However, DNA breaks down over time, and scientists think that it’s unlikely to be found in any specimen older than a million years. Dinosaurs went extinct 65 million years ago. No dinosaur DNA, no dinosaurs. Sorry!

Some other species, however, are fair game. In 2003, scientists briefly de-extincted a type of goat, called the bucardo. DNA-laden cells, taken from the last living female before she died, were used to create a clone, and the resulting embryo was transplanted into the womb of a living domestic goat.

The bucardo was delivered by Caesarean section, but died shortly after birth due to lung defects. The bucardo was therefore the first animal to be de-extincted, but also the first animal to go extinct twice!

Other de-extinction projects include attempts to revive an Australian amphibian called the gastric-brooding frog, a North American bird called the passenger pigeon and the one and only woolly mammoth. These use a combination of cloning, gene-editing and stem cell methods, but don’t hold your breath waiting for the pitter-patter of tiny feet. De-extinction is still very much in its infancy, so for now, take solace in the fact that dinosaurs never really left us. Birds are their direct descendants, and they’re everywhere.

Read more: