Two tiny dinosaurs species that lived about 160 million years ago struggled to fly despite having bat-like wings, scientists have found.

Yi qi and Ambopteryx longibrachium, which roamed the lands in China during the Late Jurassic period, only managed to “glide clumsily between the trees”.

The scientists believe these small dinosaurs, described in the journal iScience, became extinct in a very short period of time as they could not compete with other tree-dwelling dinosaurs and early birds.

“Once birds got into the air, these two species were so poorly capable of being in the air that they just got squeezed out," said Dr Thomas Dececchi, assistant professor of biology at Mount Marty University in the US and first author on the study.

“Maybe you can survive a few million years underperforming but you have predators from the top, competition from the bottom and even some small mammals adding into that, squeezing them out until they disappeared.”

Both Yi and Ambopteryx were small animals, weighing less than 1kg.

Read more about dinosaurs:

- 200 million-year-old fossil shows dinosaur 'walked like a guineafowl'

- Fossilised dinosaur skull reveals adorable appearance of baby sauropods

Researchers say that they are unusual examples of theropod dinosaurs, the group that gave rise to birds.This is because while most theropods were ground-loving carnivores, Yi and Ambopteryx were comfortable in the trees and lived on a diet of insects, seeds and other plants.

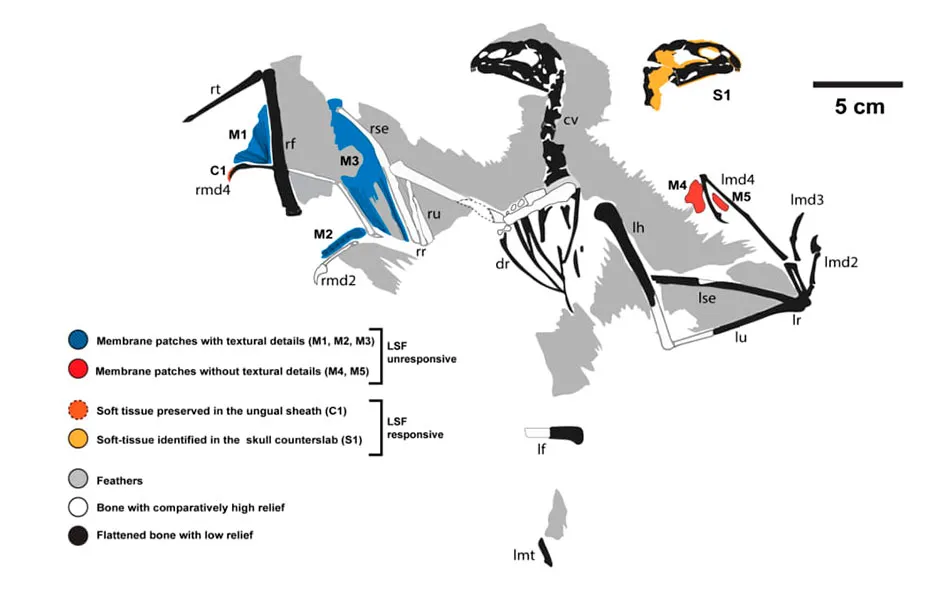

Previous research has shown that both Yi and Ambopteryx had membranous wings and a styliform, a long and pointed forelimb.Scientists have speculated that membranous wings and elongated forelimb point to a weak flying prowess.

To find out more, the researchers examined the fossils of both dinosaurs using a scanning technique known as laser-stimulated fluorescence (LSF).They focused on the soft-tissue details in the fossils that cannot be seen in standard white light.The team then used mathematical models to predict how these birds may have flown, taking into account their wingspan, weight and muscle placement.

“They really can’t do powered flight," said Prof Dececchi.“You have to give them extremely generous assumptions in how they can flap their wings.

“You basically have to model them as the biggest bat, make them the lightest weight, make them flap as fast as a really fast bird and give them muscles higher than they were likely to have had to cross that threshold. They could glide, but even their gliding wasn’t great.”

But the researchers said gliding did help these dinosaurs stay out of danger at certain times.

“If an animal needs to travel long distances for whatever reason, gliding costs a bit more energy at the start but it’s faster," Prof Dececchi said.“It can also be used as an escape hatch. It’s not a great thing to do but sometimes it’s a choice between losing a bit of energy and being eaten.”

According to Prof Dececchi and his team, the findings support the general consensus that dinosaurs evolved flight in several different ways before modern birds evolved.

They said both Yi and Ambopteryx show a “unique but failed flight architecture of non-avialan theropods” which may have contributed to their extinction.

“Once they were put under pressure, they just lost their space," Prof Dececchi added.“They couldn’t win on the ground. They couldn’t win in the air. They were done.”

Reader Q&A: What’s the largest flying animal?

Asked by: Sam Crossley, Bradford

In terms of wingspan, the largest birds are those adapted for soaring, long-distance flight. The wandering albatross is the current record holder, with a maximum recorded wingspan of 3.7 metres, but prehistoric animals were even more impressive.

Pelagornis sandersi, a bird which lived 25 million years ago, had an estimated wingspan of up to 7.4 metres. Like albatrosses, it probably took to the air by running downhill into a headwind, or launching off cliffs. However, even P. sandersi was dwarfed by some of the pterosaurs, those flying reptiles from the time of the dinosaurs.

The largest so far discovered is Quetzalcoatlus northropi, which may have weighed more than 200kg with a wingspan of 11 metres. That’s as wide as a Cessna 172 aeroplane! Computer simulations have shown that Q. northropi could soar at 130km/h and stay aloft for up to 10 days.

Read more: