Climate models may be vastly underestimating how much ice will melt in Greenland in the future, a group of scientists believe.

Their analysis is based on the record loss of Greenland ice in 2019, which researchers believe was caused not just by warm temperatures but also unusual atmospheric conditions that led to clear skies in the summer.

According to Dr Marco Tedesco, from Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, current global climate models are not able to capture the effects of a “wavier jet stream” – a phenomenon that can lead to extreme weather conditions.

As a result, he believes simulations of future impacts are significantly underestimating the mass loss due to climate change, adding: “It’s almost like missing half of the melting.”

Read more about ice melt:

- Greenland ice melt putting 40 million people at greater risk than previously thought

- Clam shell study issues dire warning over Arctic sea ice melt

The Greenland ice sheet contains enough frozen water to raise sea levels by as much as seven metres. Understanding the impacts of atmospheric circulation changes will be crucial for improving projections for how much of that water will flood the oceans in the future, Dr Tedesco said.

A team of researchers used satellite data, ground measurements, and climate models to analyse changes in Greenland’s ice sheet during the summer of 2019.

They found last year was one of the worst years on record, which saw the Greenland lose about 320 billion tonnes from the ice sheet. Before that, 2012 was considered to be the worst year for the ice sheet, with a loss of 310bn tonnes.

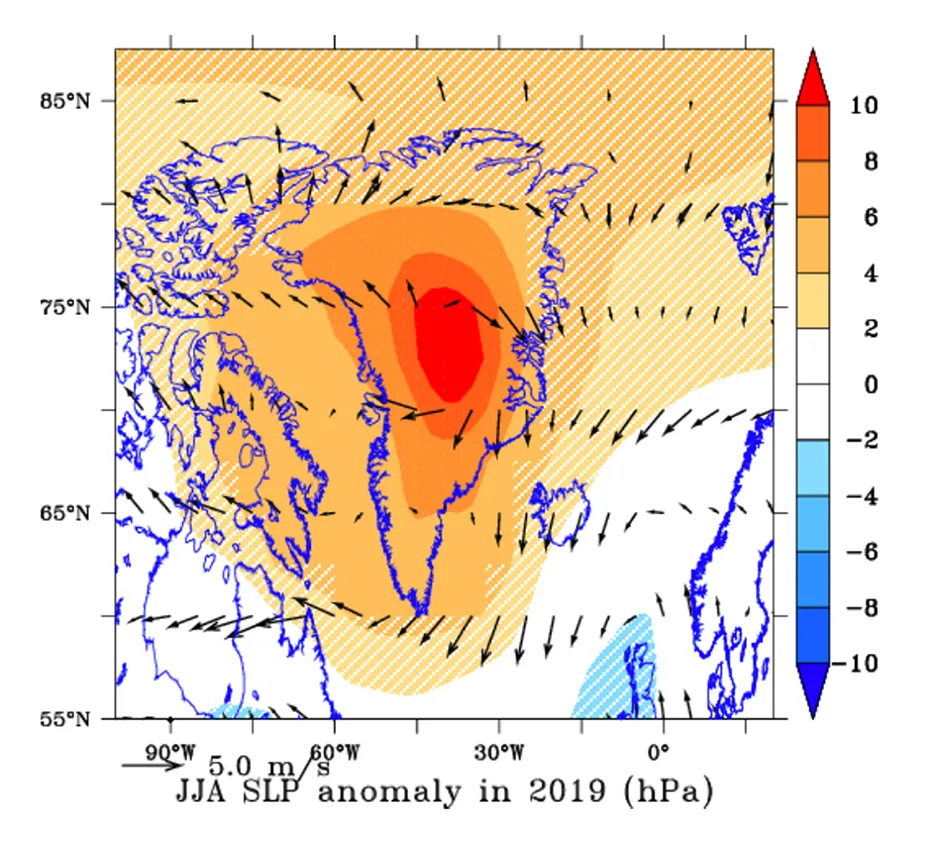

The team found the ice loss in 2019 was linked to high-pressure conditions – called anticyclonic conditions – that prevailed over Greenland for long periods of time.These conditions prevented the formation of clouds in the southern portion of Greenland, letting in more sunlight to melt the surface of the ice sheet.

According to the researchers, this resulted in about 50 billion fewer tonnes of snowfall than usual being added to the mass of the ice sheet in 2019.

Conditions were different but no better in the northern and western parts of Greenland, the team added, due to the high pressure system spinning clockwise and pulling warm, moist air into the region and creating a small-scale greenhouse effect.

The researchers believe these conditions will become more common in Greenland.

Read more about climate change:

- Rising ocean temperatures are pushing marine species towards the poles

- Saving ocean life within a human generation is 'largely achievable', say scientists

Dr Tedesco said: “These atmospheric conditions are becoming more and more frequent over the past few decades.

“It is very likely that this is due to the waviness to the jet stream, which we think is related to, among other things, the disappearance of snow cover in Siberia, the disappearance of sea ice, and the difference in the rate at which temperature is increasing in the Arctic versus the mid-latitudes.”

The research is published in the journal The Cryosphere.

Reader Q&A: If global warming increases rainfall, could the extra clouds block sunlight and help cool the Earth?

Asked by: Tristin Quinn, Tullamore, Ireland

The link between clouds and global temperature is complicated. On one hand, clouds block sunlight and reflect it back into space, cooling the Earth. On the other, they trap warmth radiating from the Earth’s surface, increasing temperatures.

The balance between these two opposing effects varies from cloud to cloud. Low clouds, for example, tend to be quite opaque, meaning that they cool the planet more than they warm it.

In contrast, wispy, high-altitude clouds allow most sunlight through but are effective at preventing heat from escaping, creating a warming effect. When you add up these effects on a global scale, clouds currently have a net cooling effect on the planet, lowering global temperatures by around 5°C.

Scientists predict that climate change will increase evaporation, leading to an increase in rainfall globally – although there will be considerable variation on a regional level. But increased rainfall does not simply translate into more clouds. Instead, changing conditions will affect how and where clouds form and how they behave.

In some areas, climate change will probably cause more low clouds to form, which could offset a rise in global temperature. In mid-latitudes, however, low cloud cover is expected to decrease.

Meanwhile, the paths followed by tropical, mid-altitude storm clouds are expected to shift towards the poles, into regions with less sunlight, dampening their cooling effect. Plus, high-altitude clouds are predicted to increase in altitude, which would have a heating effect. This is because higher clouds are colder, and absorb heat radiating from Earth just as well, but retransmit more of this heat back to Earth (rather than out into space).

It’s hard to predict how much these processes might warm the planet, as they could trigger positive feedback loops, accelerating a rise in temperature. Clouds are notoriously difficult to predict with certainty, but most climate models agree that changes in clouds will have the net effect of amplifying rising temperatures.

Read more: