The latest trial results suggest that the University of Oxford's coronavirus vaccine produces a strong immune response in older adults. It is expected to release data on its effectiveness in the coming weeks.

The ChAdOx1 nCov-2019 vaccine has been shown to trigger a robust immune response in healthy adults aged 56-69 and people over 70.

Phase 2 data, published in The Lancet, suggests one of the groups most vulnerable to serious illness and death from COVID-19 could build immunity, researchers say.

According to the researchers, volunteers in the trial demonstrated similar immune responses across all three age groups (18-55, 56-69, and 70 and over).The study of 560 healthy adults – including 240 over the age of 70 – found the vaccine is better tolerated in older people compared with younger adults.

The results are consistent with Phase 1 data reported for healthy adults aged 18-55 earlier this year.

Read more about the Oxford coronavirus vaccine:

- Coronavirus: Oxford vaccine could be put before regulators by the end of the year

- Oxford vaccine: Early trials suggest 'double protection' from coronavirus

Volunteers received two doses of the vaccine candidate, or a placebo meningitis vaccine.No serious adverse health events related to the vaccine were seen in the participants.

“Older adults are a priority group for COVID-19 vaccination, because they are at increased risk of severe disease, but we know that they tend to have poorer vaccine responses," said Dr Maheshi Ramasamy, investigator at the Oxford Vaccine Group and consultant physician.

“We were pleased to see that our vaccine was not only well tolerated in older adults, but also stimulated similar immune responses to those seen in younger volunteers. The next step will be to see if this translates into protection from the disease itself.”

Researchers say their findings are promising as they show that the older people are showing a similar immune response to younger adults.

“Immune responses from vaccines are often lessened in older adults because the immune system gradually deteriorates with age, which also leaves older adults more susceptible to infections," said study lead author Professor Andrew Pollard, from the University of Oxford.

“As a result, it is crucial that COVID-19 vaccines are tested in this group who are also a priority group for immunisation.”

Dr Ramasamy added: “The robust antibody and T-cell responses seen in older people in our study are encouraging. The populations at greatest risk of serious COVID-19 disease include people with existing health conditions and older adults.

“We hope that this means our vaccine will help to protect some of the most vulnerable people in society, but further research will be needed before we can be sure.”

The study also found the vaccine, being developed with AstraZeneca, was less likely to cause local reactions at the injection site and symptoms on the day of vaccination in older adults than in the younger group.

Adverse reactions were mild – injection-site pain and tenderness, fatigue, headache, feverishness and muscle pain – but more common than seen with the control vaccine.Thirteen serious adverse events occurred in the six months since the first dose was given, none of which were related to either study vaccine.

Read the latest coronavirus news:

- Mouthwash eliminates coronavirus in 30 seconds... in the lab

- Third COVID-19 vaccine ‘is 94.5% effective’, researchers say

The authors note some limitations to their study, including that the participants in the oldest age group had an average age of 73-74 and few underlying health conditions, so they may not be representative of the general older population, including those living in residential care settings or aged over 80.

Phase 3 trials of the vaccine are ongoing, with early efficacy readings possible in the coming weeks.

UK authorities have placed orders for 100 million doses of the vaccine – enough to vaccinate most of the population – should it receive regulatory approval.

The Oxford findings come after Pfizer and BioNTech announced that their vaccine candidate has shown 95 per cent efficacy, with a 94 per cent effectiveness in those aged 65 and over.Forty million doses of that vaccine have been bought by the UK, with rollout potentially starting in early December if the jab is given the green light by regulators.

Earlier in the week, US biotech firm Moderna released data suggesting its vaccine is almost 95 per cent effective.

How do scientists develop vaccines for new viruses?

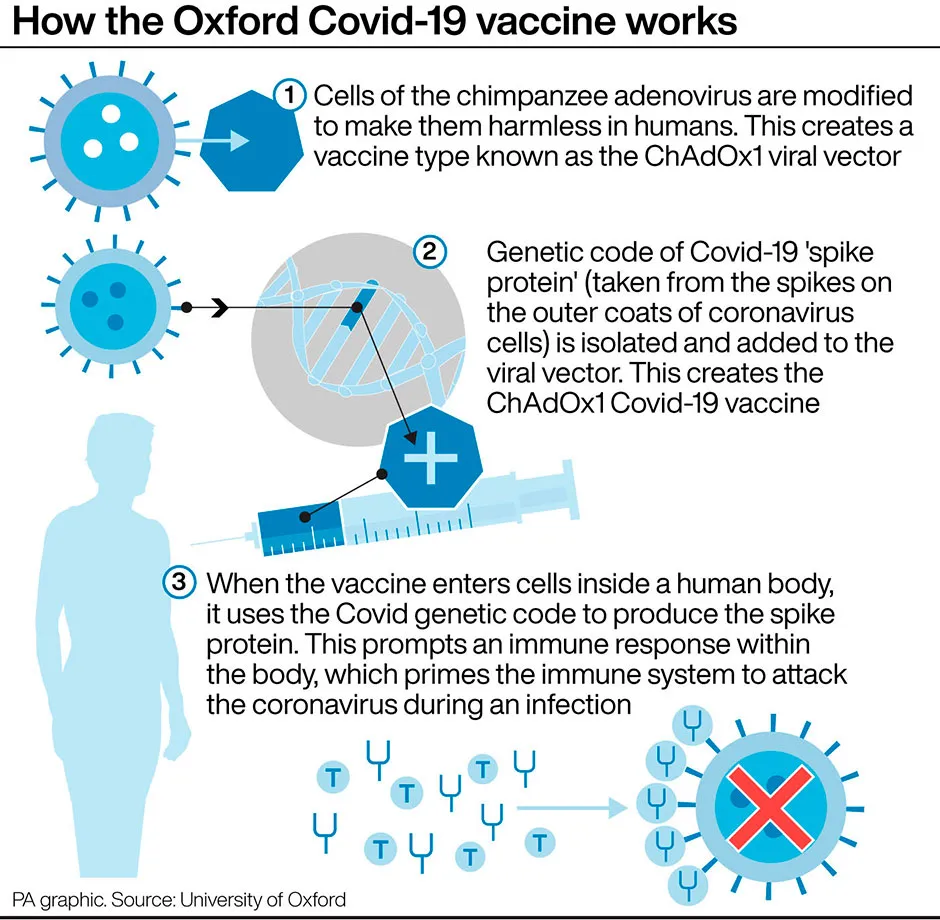

Vaccines work by fooling our bodies into thinking that we’ve been infected by a virus. Our body mounts an immune response, and builds a memory of that virus which will enable us to fight it in the future.

Viruses and the immune system interact in complex ways, so there are many different approaches to developing an effective vaccine. The two most common types are inactivated vaccines (which use harmless viruses that have been ‘killed’, but which still activate the immune system), and attenuated vaccines (which use live viruses that have been modified so that they trigger an immune response without causing us harm).

A more recent development is recombinant vaccines, which involve genetically engineering a less harmful virus so that it includes a small part of the target virus. Our body launches an immune response to the carrier virus, but also to the target virus.

Over the past few years, this approach has been used to develop a vaccine (called rVSV-ZEBOV) against the Ebola virus. It consists of a vesicular stomatitis animal virus (which causes flu-like symptoms in humans), engineered to have an outer protein of the Zaire strain of Ebola.

Vaccines go through a huge amount of testing to check that they are safe and effective, whether there are any side effects, and what dosage levels are suitable. It usually takes years before a vaccine is commercially available.

Sometimes this is too long, and the new Ebola vaccine is being administered under ‘compassionate use’ terms: it has yet to complete all its formal testing and paperwork, but has been shown to be safe and effective. Something similar may be possible if one of the many groups around the world working on a vaccine for the new strain of coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) is successful.

Read more: