A closer examination of Archaeopteryx fossils has led to a new species of the creature being identified. An international team of scientists, led by Dr Martin Kundrát from Slovakia’s University of Pavol Jozef Šafárik, have described a type of Archaeopteryx that’s closer to modern birds in evolutionary terms than any previously analysed.

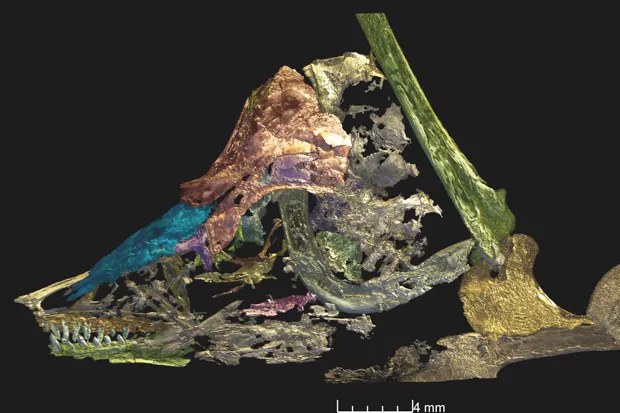

Archaeopteryx, meaning ancient wing, was first named after a solitary feather discovered in southern Germany back in 1861. Since then, only 12 specimens have been found, and they all date back to the late Jurassic period, approximately 150 million years ago. By examining the youngest of all of the known specimens, known as ‘specimen number eight’, using advanced 3D X-ray scanning techniques, the team found several distinct features about its anatomy that mark it out as being closer to modern birds than reptiles. This makes it evolutionarily distinctive enough to be described as a whole new species: Archaeopteryx albersdoerferi.

“It confirms Archaeopteryx as the first bird, and not just one of a number of feathered theropod dinosaurs, which some authors have suggested recently. You could say that it puts Archaeopteryx back on its perch as the first bird,” said Dr John Nudds of the University of Manchester and a co-author of the report on

the findings.

The team found that Archaeopteryx albersdoerferi had fused cranial bones and a complex configuration of reinforced carpals and metacarpals (hand bones). The arrangement is similar to those seen in more modern flying birds, but not in the olderArchaeopteryx species, which more closely resemble reptiles and dinosaurs.

“By digitally dissecting the fossil we found that this specimen differed from all of the others. It possessed skeletal adaptations that would have resulted in much more efficient flight,” said Nudds. “In a nutshell we have discovered what Archaeopteryx lithographica [other Archaeopteryx specimens] evolved into – a more advanced bird, better adapted to flying – and we have described this as a new species of Archaeopteryx.”

Expert comment

Dr Darren Naish - Palaeontologist, University of Southampton

Despite being known to science for 160 years, the iconic ‘first bird’Archaeopteryxremains a popular area of research. For specialists, the significance of Dr Kundrátand his team’sstudy is that it provides quality information on the anatomy of a specimen not studied in detail before.Archaeopteryxmight be familiar as fossil animals go, but surprisingly little has been published on its anatomy.

It is, however, two other aspects of the study that have captured the most attention. The first is that the specimen is identified as a new species. Until recently, allArchaeopteryxspecimens were thought to belong to the sole species:A. lithographica. But since 2001, experts have agreed that several species are involved. Perhaps this view isn’t surprising given that these animals inhabited a tropical archipelago: an environment where the existence of several closely related species would be predicted. The downside to this view is that several specimens are now in limbo. They seem to be part ofArchaeopteryx, but their precise classification is unresolved and more research is needed.

The team’s second main contention is that they have successfully pinnedArchaeopteryxdown on the dinosaur family tree. It is, they say, a member of the bird lineage (termed Avialae), and not part of one of a number of other groups closely related to Avialae, such as the VelociraptororTroodonlineages. The possibility thatArchaeopteryxmight not be part of the bird lineage has been promoted in a few studies, and while this it is not an especially popular view, it does seem to be overturned by the new data reported in this study.

This is an extract from issue 329 of BBC Focus magazine.

Subscribe and get the full article delivered to your door, or download the BBC Focus app to read it on your smartphone or tablet. Find out more