Mastering a new skill can take hours of dedicated practice. Now, a team of researchers studying mice at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York have shed light on what happens in the brain as a new skill is acquired by successfully mapping the changes that occur in the wiring of cell circuits and the performance of neurons.

The finding could lead to a deeper understanding of how learning a skill alters different parts of the brain and maybe even lead to new methods to improve learning, they say.

The team trained the mice to respond to a series of flashes and clicks by licking one of 3 waterspouts in front of them. They licked the middle spout to start the trial, one side to report a high-rate of clicking and flashing and the other side to report a low-rate of flashing and clicking. When the mice made the correct decision, they received a reward.

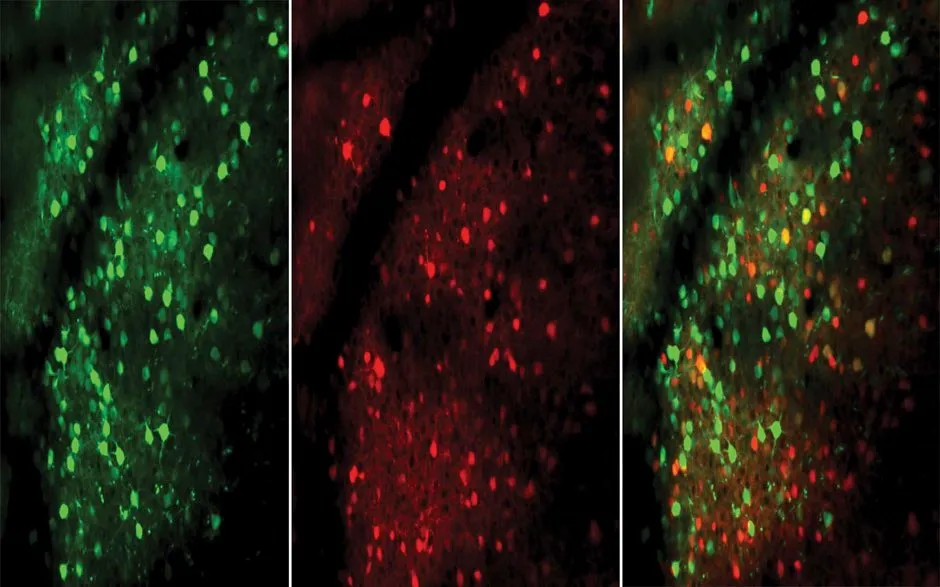

The researchers then monitored the mice’s brains over the course of several weeks using state-of-the-art imaging techniques, tracking the changes as the mice got better and better at the task.

Over time, the neurons used by the mice in the task became more fine-tuned, only firing when the correct decision was made, and also started to react more quickly.

Read more about the brain:

When the animals were just beginning to learn, the neurons didn’t respond until around the time it made the choice. But as the animal gained experience, the neurons responded much further in advance, indicating a much higher level of expertise.

“We recorded the activity from hundreds of neurons all at the same time, and studied what the neurons did over learning,” said CSHL Associate Professor Anne Churchland, the senior author on the study.

"Nobody really knew how animals or humans learn the structure of a task and how the neural activity supports that. Most decision-making studies focused on the period where the animals are really experts. But we were able to see how they arrive at the state by measuring the neurons in their brain all the way through learning,” said Churchland.

“We found that in all the animals, their learning occurs gradually over about 4 weeks. And we found that what supports learning is activity changes in a whole bunch of neurons.”