Tropical forests can still act as effective carbon sponges in a warmer world, research across three continents has found, but only if nations act quickly to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

A team of researchers coordinated by the University of Leeds found that rainforests can continue to absorb huge volumes of carbon if global warming remains less than 2°C above pre-industrial levels, the target set out by the Paris Climate Agreement.

The paper, which was published in the journal Science, showed that if the average daytime temperature during the warmest month of the year was above a threshold of 32°C, the tropical forests’ ability to store carbon starts to diminish.

Read more about climate change:

- Tropical forests could switch from a carbon sink to a carbon source in the next 20 years

- The ocean captures twice as much carbon dioxide as previously thought

- Amazon rainforest could take only 50 years to collapse, study suggests

Currently, 25 per cent of tropical rainforests are above this 32°C threshold, and store less carbon than their cooler counterparts.

Under the 2°C scenario – in which average global temperature has risen by 2°C – tropical forests will actually be 2.4°C hotter than today, due to the fact some regions warm faster than others, lead author Dr Martin Sullivan told the PA news agency.

This would push three-quarters of all tropical forests above the 32°C “safety zone”, and begin the rapid release of carbon back into the atmosphere.

The world’s tropical forests store an estimated 25 years worth of fossil fuel emissions in their trees.

Every degree of further warming above the 32°C threshold releases four times as much carbon as would have been released compared to below this point, the research found.

Fragmentation of these forests through fire and logging could also impede tree species’ ability to adapt to a changing world, even if warming is kept below 2°C.

Dr Sullivan, from the University of Leeds and Manchester Metropolitan University, said: “Our analysis reveals that up to a certain point of heating tropical forests are surprisingly resistant to small temperature differences.

“If we limit climate change they can continue to store a large amount of carbon in a warmer world."

“The 32°C threshold highlights the critical importance of urgently cutting our emissions to avoid pushing too many forests beyond the safety zone,” Dr Sullivan added.

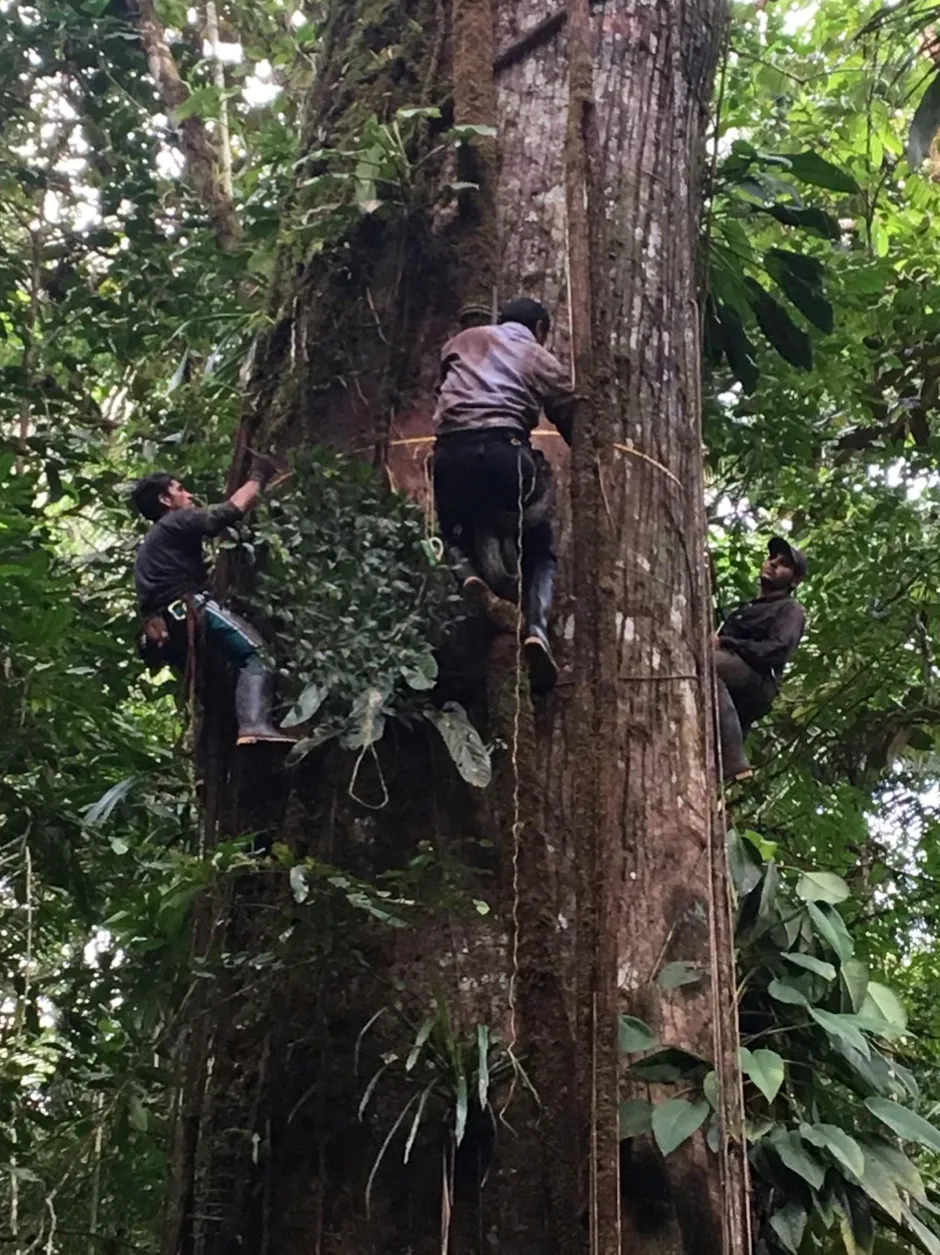

An international team of 225 researchers measured the height and diameter of trees in sample plots in 813 forests across the tropics to calculate how much carbon they stored.

Over the course of the study, nearly two million measurements were taken from 10,000 species of tree in 24 countries across South America, Africa and Asia.

Data gathered on some of the plots dates back to the early 1960s. The sites were revisited every few years to measure how much carbon was being absorbed and how long it was stored before the tree died.

Imagine if we take this chance to reset how we treat our Earth. We can keep our home cool enough to protect these magnificent forests – and keep all of us safer

Professor Oliver Phillips, University of Leeds

Co-author Professor Beatriz Marimon, from the State University of Mato Grosso in Brazil, said: “Our results suggest that intact forests are able to withstand some climate change.

“Yet these heat-tolerant trees also face immediate threats from fire and fragmentation.”

“Achieving climate adaptation means first of all protecting and connecting the forests that remain.”

The research suggested that in the long term, rising temperature has the greatest negative effect on forest carbon stocks by reducing growth, with drought killing off trees the second biggest factor.

South America’s forests are projected to see the greatest long-term reduction in carbon stocks, as baseline temperatures are highest in the region, and future warming predicted also to be highest.

Professor Oliver Phillips, of the University of Leeds, urged world leaders to take the opportunity offered by the current shutdown to transition towards a stable climate.

“Imagine if we take this chance to reset how we treat our Earth. We can keep our home cool enough to protect these magnificent forests – and keep all of us safer,” he said.

Reader Q&A: How many trees does it take to produce oxygen for one person?

Asked by: Aaron Hacon, Norwich

Trees release oxygen when they use energy from sunlight to make glucose from carbon dioxide and water. Like all plants, trees also use oxygen when they split glucose back down to release energy to power their metabolisms. Averaged over a 24-hour period, they produce more oxygen than they use up; otherwise there would be no net gain in growth.

It takes six molecules of CO2 to produce one molecule of glucose by photosynthesis, and six molecules of oxygen are released as a by-product. A glucose molecule contains six carbon atoms, so that’s a net gain of one molecule of oxygen for every atom of carbon added to the tree. A mature sycamore tree might be around 12m tall and weigh two tonnes, including the roots and leaves. If it grows by five per cent each year, it will produce around 100kg of wood, of which 38kg will be carbon. Allowing for the relative molecular weights of oxygen and carbon, this equates to 100kg of oxygen per tree per year.

A human breathes about 9.5 tonnes of air in a year, but oxygen only makes up about 23 per cent of that air, by mass, and we only extract a little over a third of the oxygen from each breath. That works out to a total of about 740kg of oxygen per year. Which is, very roughly, seven or eight trees’ worth.

Read more: