Scientists have levitated groups of particles using sound for the first time, in an experiment which could lead to breakthroughs in robotics, and even provide insights into how planets and moons take shape.

Acoustic levitation is a technique that uses the pressure from intense sound waves to suspend objects in mid-air. So far, it's already been used to levitate water droplets, two-inch polystyrene balls, and even living insects. In the latest demonstration of the technology, scientists at the University of Bath and the University of Chicago kept multiple plastic particles in the air at the same time, seeking to find out how materials cluster and interact with each other when they're free to move and not restricted by a flat surface.

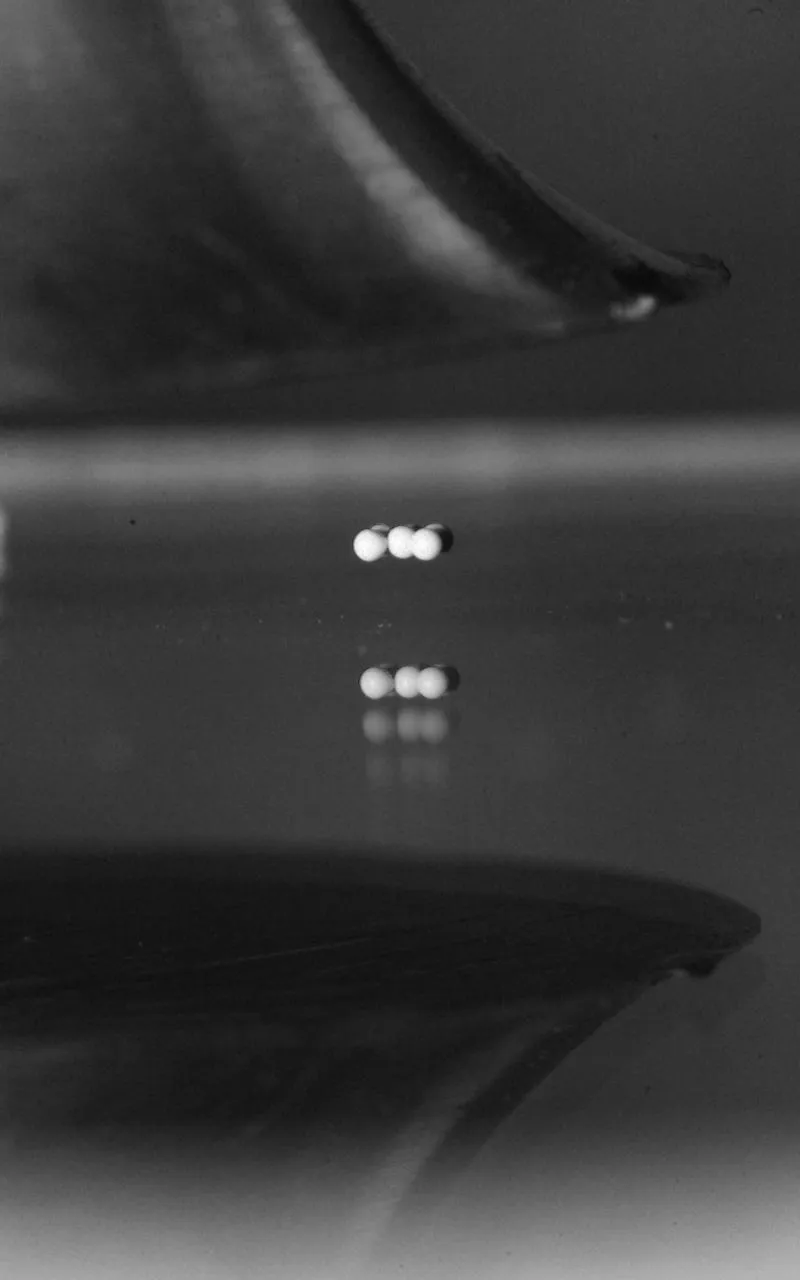

The researchers used 'ultrasonic' sound waves, at frequencies above the range of human hearing, to levitate particles of approximately 1mm in diameter, made from polyethylene - the common plastic used in carrier bags and shampoo bottles.

Using high-speed cameras, they found that five particles or fewer only cluster together in one configuration. Adding another particle to the mix makes things more interesting, with the six particles forming three different shapes: a parallelogram; a chevron; and a triangle. Upping the number of particles to seven creates even more complex configurations, with the particles clustering into one of four shapes, resembling either a flower, a turtle, a tree, or a boat.

"We've found that by changing the ultrasound frequency, we can make the particle clusters move about and rearrange," said Dr Anton Souslov, co-author of the study and physicist at the University of Bath. "Six particles is the minimum needed to change between different shapes."

As they changed the frequency of the sound waves, the researchers found that one particle would act as a kind of 'hinge', swinging around the other particles to reconfigure the cluster into a new formation.

"This opens up new possibilities for manipulating objects to form complex structures," said Souslov. "Maybe these hinges that we observe could be used to develop new products and tools in the fields of wearable technology or soft robotics - where scientists and engineers use soft, manipulable materials to create robots with more flexibility and adaptability than those made from rigid materials."

The most exciting application of this technology, however, is perhaps in the world of astrophysics. Celestial bodies such as planets, moons and asteroids form from immense disks of gas and dust. As these 'protoplanetary' disks rotate, the matter begins to stick together into clumps, which gradually get bigger as they exert a larger gravitational pull on the surrounding material.

This new experiment could provide a way for astrophysicists to study this process in real-time on a smaller scale, levitating particles of dust in the lab in order to understand how planets and moons form as the cosmic dust swirls and clumps into larger structures.

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard