Reptile populations on Australia's Christmas Island have been in serious decline over the past few decades. Of the five endemic species, two of them – the blue-tailed skink and Lister’s gecko – have entirely disappeared from the wild. While habitat loss and predation by invasive species have played a major part in the decline, a silent killer has also been causing the lizards to mysteriously die.

Lizards bred in captivity have been dying too, leaving the two species – which only number around 1,000 individuals each – at serious risk of extinction.

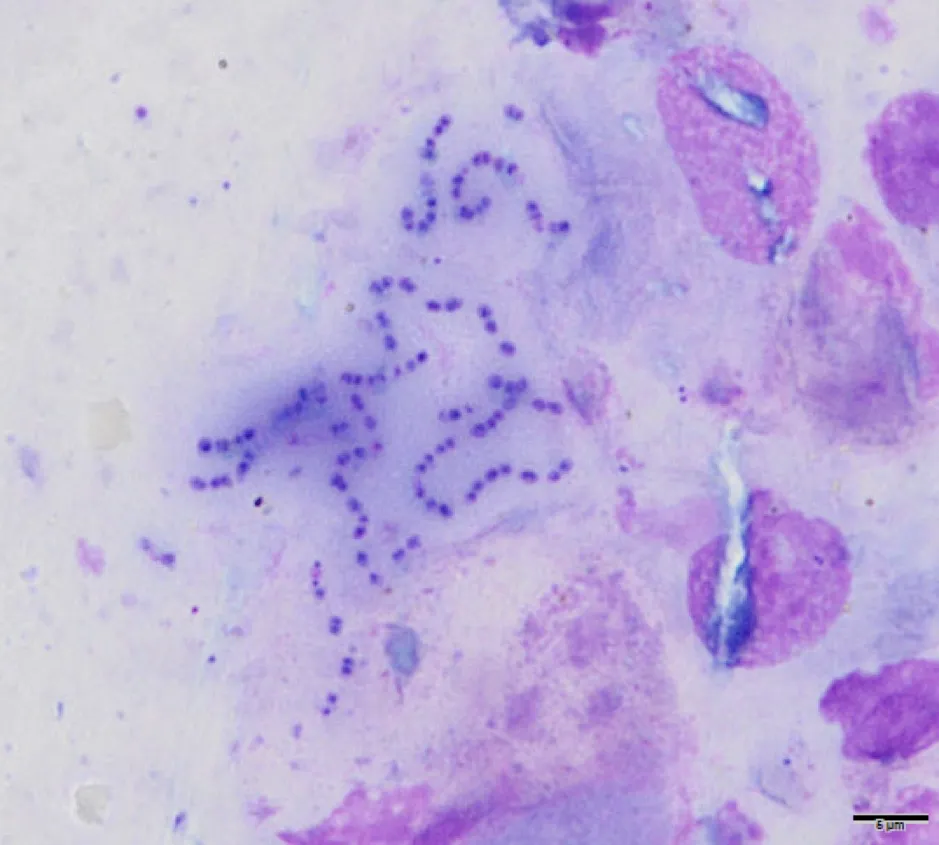

Australian scientists have now identified the culprit to be a new strain of bacterium called Enterococcus lacertideformus, which grows in the animal’s head and internal organs, leading to facial swelling, lethargy and eventual death. It can be spread by direct contact via the reptiles’ mouths or by biting, which is common during breeding season.

As well as identifying the bacterium, the researchers used genome sequencing to decode its genetic structure.

“We also found that the bacterium can surround itself with a biofilm – a ‘community of bacteria’ that can help it survive,” said Jessica Agius, co-lead researchers and PhD candidate in the Sydney School of Veterinary Science.“Understanding howE. lacertideformusproduces and maintains the biofilm may provide insights on how to treat other species of biofilm-forming bacteria.”

When looking through the genetic code, the researchers discovered that it should be possible to kill the bacterium with antibiotics, which means that they may be able to treat infected animals.

In a further effort to ensure the threatened reptiles survive, Agius has played a role in establishing a population of blue-tailed skinks on the Cocos Islands, which are free of predators believed responsible for the skinks’ decline. She tested the reptiles on the Cocos Islands to ensure they were free of the bacterium.

“It’s critical we act now to ensure these native reptiles survive,” Agius said.

Threats to Christmas Island's wildlife

Christmas Island is located in the Indian Ocean, and lies about 360km south of Java. Despite its tiny size (it measures around 19km by 14.5km) it has incredibly diverse wildlife, with many species only being found on the island and nowhere else. Roughly two-thirds of the island has been declared a national park, and includes rainforests, coral reefs, wetlands and seashore.

Its most famous animal resident is perhaps the Christmas Island crab. Each year, millions of these land crabs will make a spectacular annual mass migration to the sea to lay their eggs. They are an important species on the island, as they feed on fallen fruits and leaves, as well as seedlings and carrion. They also dig burrows and fertilise the ground with their excrement, all of which improves the soil. However, they are not the only crabs on the island – there are around 50 native species.

The island was not settled by humans until the late 1800s, and there are no large, native terrestrial mammals. The introduction of rats, cats and dogs has led to declines or extinctions of native mammals.

Other introduced species, such as the common wolf snake and giant centipede have also been implicated in the decline of the island’s native fauna.

Perhaps the most destructive invasive animal is not a large mammal, but the brilliantly named 'yellow crazy ant'. The iconic Christmas Island crab has seen its numbers drop following the accidental introduction of the ant in the first half of the 20th Century.

With no predators on the island, the yellow crazy ant can form enormous supercolonies, with densities of up to 2,254 foraging ants per square metre. The ants have killed millions of crabs, which in turn has affected the diversity of plants found in the rainforest: with fewer crabs eating the seedlings, weeds have flourished.

But it’s not just the red crabs that have been affected by the invasive ant. Yellow crazy ants will also chomp their way through native frogs and lizards, as well as bird nestlings.

Currently, there are programmes in place to try and control the ants on the island.

Read more: