In robotics, the term the ‘uncanny valley effect’ is used to describe the revulsion and feelings of unease that arise when we are confronted by a computer-generated figure or robot that appears to be almost, but not quite, human.

The effect is also seen in monkeys, which makes studying their social behaviour using animated monkey faces particularly difficult.

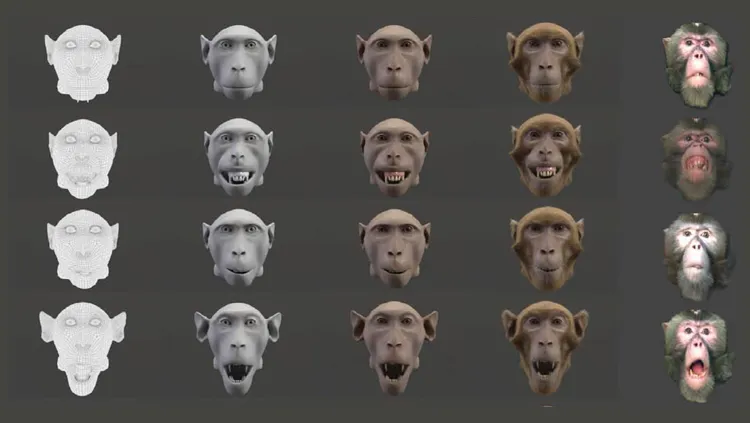

Now, researchers from the University of Tübingen, Germany have overcome this problem by creating a more realistic avatar using technology borrowed from the film special effects industry – the graphics package Autodesk Maya – based on photographic reference and MRI scans.

Read more about animal behaviour:

- The pinkest flamingos are the most aggressive, study finds

- Cannibal dinosaurs may once have roamed late-Jurassic Earth

The team compared how Rhesus monkeys reacted toward five types of monkey faces: video footage from real monkeys, a natural-looking avatar with fur and facial details, a furless avatar, a greyscale avatar, and a wireframe face.

The monkeys looked at the wireframe face but avoided looking at the furless and greyscale avatars, showing the uncanny valley effect at work. However, the natural-looking avatar with fur overcame this effect.

The monkeys looked at the model and made social facial expressions, comparable to how they would act around real monkeys. Using this type of avatar will make social cognition studies in monkeys more standardised and replicable, and the technology may even help with research into human communication, the researchers say.

“We want to use the naturalistic avatar to systematically investigate in a fully controlled manner how monkeys perceive and react to their conspecifics’ gaze and facial expressions,” said lead researcher Ramona Siebert.

“Understanding how the system works on a neuronal level might offer insights into the nature of the communication deficit in human autism spectrum disorder, which is characterised by problems understanding the facial information of others.”

How do gorillas communicate?

Animals communicate with one another using a plethora of signals: tropical fish use neon technicolour, songbirds tweet sweet melodies and gorillas, new research has shown, may communicate using social odour cues.

Using chemosensory information, such as scent, to convey a message is a universal ability of all living things. Bacteria aggregate together using chemical cues, and everything from beetles to humans are thought to involve chemical signaling in courtship and sexual reproduction.

However, these cues aren’t true examples of social information because they’re not intended to influence the behaviour of other individuals. For example, a female fruit fly will emit a sex hormone to announce her willingness to mate regardless of whether males are nearby; the odour is merely an advertisement.

That’s where gorillas are different. Michelle Klailova, from the University of Stirling, has found that silverback gorillas modify their odour emissions in the presence of other group members, which results in changes in social behaviour. What’s more, gorillas will alter the intensity of their odour messages depending on the social context. For example, more intense odours are released in events of anger or stress.

But why use odours to communicate? Klailova suggests this form of communication is particularly useful in Central African forests, where limited visibility drives the need to rely on other senses.

"No study has yet investigated the presence and extent to which chemo-communication may moderate behaviour in non-human great apes,” Klailova says. “We provide crucial ancestral links to human chemo-signaling, bridge the gap between Old World monkey and human chemo-communication, and offer compelling evidence that olfactory communication in hominoids is much more important than traditionally thought."

Read more: