Everyone likes a fruity smoothie in the summer, but a mosquito smoothie might end up being more beneficial to your health.

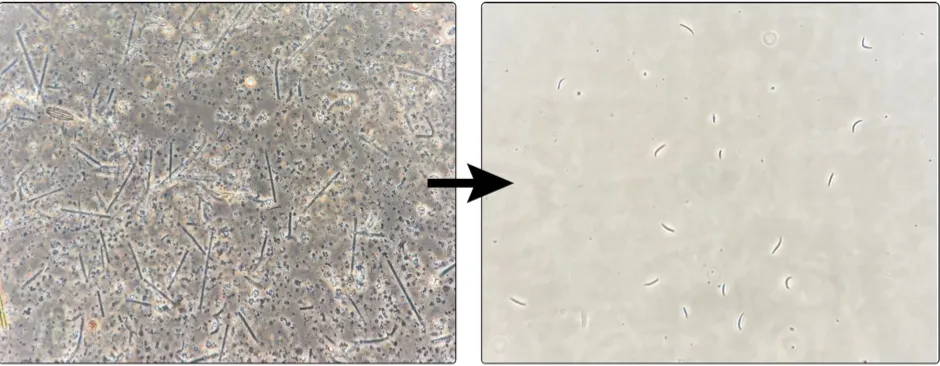

Scientists at Imperial College London have developed a new way of extracting malaria parasites from infected mosquitoes by processing the whole insects into a slurry, then filtering it to isolate the parasites to use in the vaccine. This method allows the quick extraction of more parasites with less contamination, which could lead to the development of better malaria vaccines.

The malaria parasite, Plasmodium, is spread through the bites of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes. The malaria parasite is becoming more resistant to antimalarial drugs, while mosquitoes are becoming more resistant to pesticides. Better ways of treating malaria is therefore a matter of urgency, as the disease claims some 400,000 lives per year, with 61 per cent of those being children under five.

Read more about mosquitoes:

- Scientists discover what makes blood so tasty to mosquitoes

- Five ways deadly diseases carried by mosquitoes have steered the course of human history

The existing method of creating malaria vaccines involves the dissection of young parasites – known as sporozoites – from the mosquitoes’ salivary glands by highly skilled technicians. To develop the vaccine, the parasites are then ‘attenuated’, so they produce an immune response without causing illness. However, several doses of these vaccines are needed, with each dose potentially requiring hundreds of thousands of sporozoites.

This new method is much faster and doesn’t require any fiddly dissection.

"Creating whole-parasites vaccines in large enough volumes and in a timely and cost-effective way has been a major roadblock for advancing malaria vaccinology, unless you can employ an army of skilled mosquito dissectors,” said lead researcher Prof Jake Baum. “Our new method presents a way to radically cheapen, speed up and improve vaccine production.”

But speed and cost are not the only benefits. The scientists also found that the sporozoites extracted using the new method were purer, with fewer contaminants than the traditional method. The sporozoites were also more infectious, which may allow vaccines to use lower sporozoite doses.

"With this new approach we not only improve the scalability of vaccine production, but our isolated sporozoites may actually prove to be more potent as a vaccine, giving us additional bang per mosquito buck," said first author of the study Dr Joshua Blight.

The new vaccine showed good results in rodent trials, providing 100 per cent protection from malaria when injected into the bloodstream. The researchers are now scaling up the process so they can start human trials.

Reader Q&A: Why do mosquito bites itch so much?

Asked by: Duncan Borg Conti, Malta

When a mosquito bites, she injects saliva containing anticoagulant enzymes into the wound. The first time you are bitten, nothing happens, but your immune system then begins making antibodies that bind to these foreign proteins.

For a while, this immune reaction will cause itchy, swollen bumps. Over many years this response will fade away, but if you go a long time without being bitten, it can start again the next time you are exposed.