Since President Trump’s inauguration in January 2017, there has been a steady stream of media coverage highlighting Russia’s use of disinformation and scandal in influencing the US presidential elections and the Brexit referendum in the UK.

Yet, for well over a century, Washington used surprisingly similar clandestine tactics in its exercise of global power, from pacification of the Philippines in 1898 to recent cyber-surveillance of European allies.

Read more 2019 science breakthroughs:

The Philippines was just one of the sprawling empire of tropical islands that Washington took from Spain in 1898 – but it was the only one to challenge the US army, with guerrilla resistance and messianic revolts. Using America’s advanced information systems of telephone, telegraph and automated tabulating (using a kind of proto-super-

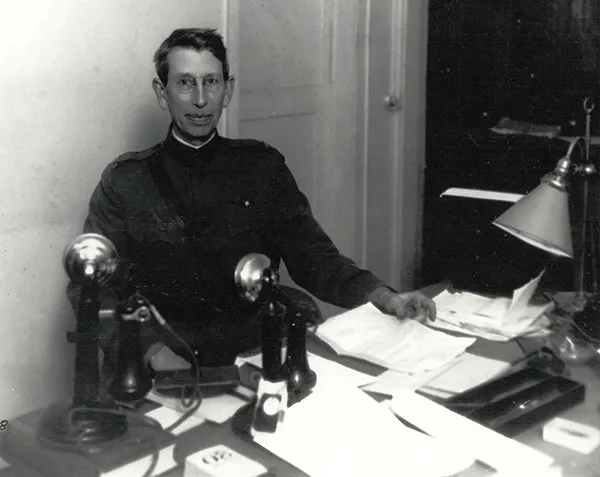

computer), the army formed the first field intelligence unit in its 100-year history. Under Captain Ralph Van Deman, dubbed the ‘father of US military intelligence’, the unit compiled detailed data on the appearance, finances and loyalties of every influential Filipino. Simultaneously, the American colonial regime created a constabulary that ruled through a total control over information, releasing scurrilous titbits to discredit dissidents and suppressing scandal to protect collaborators.

When the US entered the First World War in 1917 it had no intelligence service, so Van Deman was assigned to establish one. With a staff of 1,700 and 350,000 citizen operatives, his Military Intelligence Division launched intensive surveillance of domestic subversives – arguably the world’s most extensive programme of the kind up to that time.

After retiring in 1929, Van Deman made his San Diego bungalow the epicentre of an intelligence exchange among military, police and private security, compiling dossiers on 250,000 dissidents and channelling classified information to citizen groups for public blacklisting. During the 1950 race for the US senate, Richard Nixon reportedly used Van Deman’s files to smear his rival for the California seat, launching his path to the presidency.

During the early years of the Cold War in the 1950s, Washington carried out 170 clandestine operations in 48 nations. Over the next 50 years, the CIA would covertly manipulate 80 elections worldwide and, when such efforts failed, promote many of the military coups that roiled more than 30 nations between 1958 and 1975. Under a secret treaty signed in 1946, the National Security Agency (NSA) and its British counterpart GCHQ built a worldwide signals surveillance through the Five Eyes coalition of the US, the UK, Australia, New Zealand and Canada, with its Echelon surveillance programme, established in the 1960s.

War on terror

With the launch of the so-called ‘Global War on Terror’ in 2001, Washington merged new tech such as electronic surveillance, biometric ID and aerospace innovation into a digital information regime. By 2008, the US army had collected more than one million Iraqi fingerprints and iris scans that its combat patrols accessed by satellite link to the US. At the same time, the Joint Special Operations Command’s integrated database identified alleged Al-Qaeda operatives for elimination by drone strike. As Washington withdrew from Iraq, this tech migrated to Afghanistan, where US patrols regularly scanned Afghani eyes into an upgraded biometric automated toolset.

Iranian intelligence hacked into a CIA drone and forced it to land in public

By the time Obama took office in 2009, the NSA had assembled the requisite technological toolkit of supercomputers and data farms to sweep up billions of communications worldwide while targeting specific individuals. In 2013, the New York Times reported that there were “more than 1,000 targets of American and British surveillance in recent years”, including leaders of dozens of nations including France and Germany. Seeking diplomatic advantage over its allies, the US conducted “widespread surveillance” of world leaders during the G20 summit in Toronto in 2010. Three years later, NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden charged that “they even keep track of who is having an affair or looking at pornography, in case they need to damage their target’s reputation”.

In the marketplace of military ideas, even a crushing technological advantage is quickly lost. Washington was fast to weaponise the internet, forming its Cyber Command in 2009 and deploying computer viruses against Iran’s nuclear facilities. Russia was not far behind, using cyberstrikes to cripple Georgia’s computers in 2008 and later to disable Ukraine’s electrical grid, leading NATO’s 2016 summit to make the web a new domain for military operations.

Not only did a St Petersburg “troll factory” try to influence the 2016 US elections, but Russian hackers also stole some of the NSA’s top-secret cyber tools. Showing the accessibility of cyberwar even to secondary powers, in 2011 Iranian intelligence hacked into the navigation of a super-secret CIA drone and forced it to land for public display in northern Iran.

The digital surveillance and cyberwarfare that seemed, just a few years ago, to provide wonder weapons for extending US global dominion have quickly become just another dangerous arena for military conflict, accessible to powers large and small. It’s inevitable that in 2019, and years to come, cyber-surveillance will continue to be commonplace.

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard