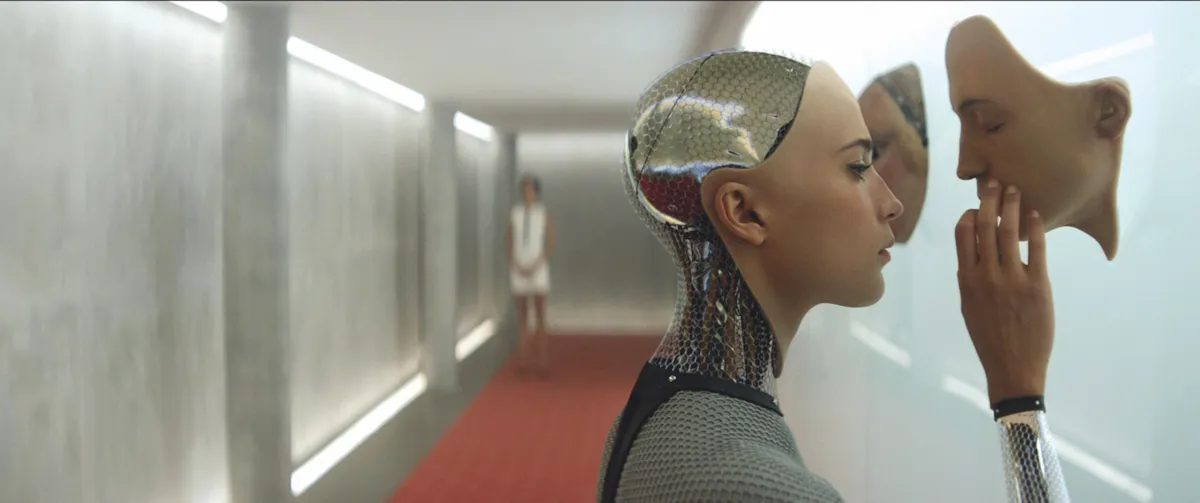

Alex Garland’s debut film about artificial intelligence, Ex Machina, blew our minds. His next film,Annihilation, is out now on Netflix so we caught up with its science consultant Adam Rutherford to find out how it’s stranger, scarier and smarter than its predecessor…

How involved were you in the creation ofEx MachinaandAnnihilation?

ForEx Machina, Alex Garland [the director] described it as a sanity check. I was there to look at how scientifically plausible the dialogue was. We wanted to make sure that there weren’t any of what we would call ‘2012moments’. In the film2012, the Earth is being destroyed by some sort of cosmic event and there’s this key moment in it when your cookie cutter scientist looks at the screen and says something like “the neutrinos are mutating”. Of course, this is a hilariously meaningless phrase.

Scientific verisimilitude is important to Alex, even more so than to me. In fact, there were lots of times during both films where I said, “I’m not sure this matters,” but he wanted both films to reflect the way we talk about science and the kinds of breakthroughs that are being made.

How did you land such a great gig?

I’d worked on a couple of films already. I’d worked onWorld War Z,The Kingsmanand with Björk on her movie ofBiophilia.

I got a call from a friend who said they knew someone who was writing a screenplay that needed a scientific hand. I said I’d help. Then five minutes later I got an email from Alex and I spat my coffee out. We’ve worked together ever since.

What sci-fi do you love?

I’ve got pretty catholic tastes, to be honest. The sci-fi that I love inmovie form is pretty predictable. I find that there isn’t much that’s super high quality, so I like films likeBlade RunnerandAliensbut also2001. I adoreSolaris, both versions. I enjoy films driven by ideas, but they need to have good plots, great performances and good special effects, so I wouldn’t want to restrict myself. One of the reasonsEx Machinaworked so well is that really it’s a horror film, and you don’t realise it’s a horror until about three-quarters of the way through.Annihilationhas a similar effect.

I’ve worked on other alien movies before and the joke in Hollywood is that the studio always says “give mesomething I’ve never seen before”. That’s a hard thing to do, but I guarantee you’ve never seen anything like what’s inAnnihilation.

Jeff VanderMeer’s novel that inspired this film is an eerie, dream-like experience. How did you balance recreating this with the film’s science?

It’s all in the writing, really, and in the power of the visual effects. Both the book and the film look atthe nature of mutation and self-destruction. But when it came to putting these ideas on screen we had to think specifically about how these mutations might manifest themselves.

The trailer reveals these bizarre cross-species mutations the scientists come across, like a crocodile with shark’s teeth, and plants in humanoid structures. The story just requires these things to be creepy. But such is Alex’s interest in the science that he was quizzing me about how it could happen. On the one hand the answer is no, that’s not really how biology works, but on the other, if it did happen then we looked at all the means by which [these mutations] could occur. We specifically talk about Hox genes, for example, which are the body plan genes. Alex has this desire to not have things that are scientifically ridiculous, to have the dialogue talk about the nature of cell biology or genetics in such a way that it creates a strong foundation for the film.

What about Natalie Portman’s character of the biologist, whose background is closest to your own. How involved were you in her direction?

I worked with all of the cast. They all wanted to know how a scientist would react – what they would think, how they would feel, and all of that isburied in their amazing performances.

Whenever I’ve worked with actors, I’ve been asked loads of questions that no one in real life is ever interested in. All of a sudden you’re opposite Natalie Portman who’s asking me “why are you like this?”. It’s a weird position to be in for sure. In a sense,I don’t necessarily think that scientists have a different mindset to anyone else. Of course, you might lean in certain directions, but it’s nice to see a bunch of scientists on screen represented as people with a bunch of personality problems. I can’t praise their performances enough.

In the book, the biologist recalls a starfish – the destroyer of worlds – that fascinated her so totally, that it, in part, drew her into a career in biology. Did you ever have an engram like that?

I was clearing out some old photos the other day, and we came across a photograph of me in my bedroom and on the wall there are two visible pictures. One is a picture of Han Solo kneeling above the tauntaun inThe Empire Strikes Backand the other is a cut-out picture of a nautilus from David Attenborough’s book from the television seriesLife On Earth. I was never pushed in a particular direction but it was clear from that photo, 40 or so years after it was taken, that my interests are almost exactly as they were as a young boy. I suppose in both pictures there’s an interest in the unreality of science and science fiction. The nautilus, which is this totally weird creature, is completely alien and bizarre. Maybe that is my equivalent of the biologist’s destroyer of worlds.

Science often is as strangeas science fiction…

The more we understand about ethology [the study of animal behaviour] the more we realise how little we really know. We’re so anthropocentric in the way we understand biology. In actuality, animal behaviour is so baffling and so alien to our sensibilities.

I have just written a whole section in my new book on sex in nature. The diversity of non-reproductive sex behaviour is astonishing. We humans spend a lot of time having sexual relations that are not really capable of producing babies. I ran some of the numbers on it for the book and estimated that the proportion of sex that could result in a baby is actually something like 1 in 1,000. You would presume that cannot be the same in nature. The number should lean more towards the act of reproduction. But the answer is no, not in the slightest. Homosexual behaviour is almost universal in animals. Necrophilia is extraordinarily common. I could go on and on.

You know, some estimates suggest that 9 out of 10 sexual encounters in giraffes are male to male. That says something about how evolution uses the tools in front of it. Sex is clearly important, or else it wouldn’t be almost universal in animals, but what evolution has done in the one or two billion years since sex evolved is turn it into a tool for a bunch of stuff of which we have almost no understanding. Yet we transpose our own behaviour and assume there’s a shared evolution route or a shared purpose on convergent behaviours. The truth is, I think we just have no idea. We don’t know what male giraffes are doing when they have sex. It’s homosexual, yes, but is it the same as homosexuality in humans? Who knows?

So are some things just unknowable?

I’m an empiricist, so I think all things are knowable. We’ll get there. We’re just incredibly good at applying anthropocentric views to this type of behaviour. The scientist, George Murray Levick, on Robert Scott’s fatal trip to the Antarctic – 1910 to 1912 was the expedition – was the first person we know of to document necrophilia and aggressive sexual coercion in penguins. He described it as deviant and appalling behaviour, and as such it’s expunged from the record. He took a very Edwardian view of all this interesting behaviour. In reality, it has nothing to do with necrophilia as a psychological abnormal pathology – we have no idea why they’re doing this.

What I am saying is that I think the whole point of science is to remove ourselves from our understanding of nature – that’s why we invented the scientific method. We have a minuscule view of the Universe as it actually is compared to how we perceive it. The whole reason we invented the scientific methodology is to cancel that out. I think we’re better at it and have a better understanding than we’ve ever had. But I just think we get blasé because we see David Attenborough documentaries and we have an industrial version of biology these days.

We think that we are at the point of just filling in the details because we have figured out evolution. But the truth is that almost all nature is unobserved and has been unobserved through history.

There’s been a wealth of thought-provoking science fiction recently. Do you think that reflects how fast our world is changing?

I’d love to say it might be a reflection of some sort of societal ideas emerging. But honestly, I think it’s a reflection of Hollywood, which is a business. I thinkEx Machinawas a part of this, because it clearly showed that 18-rated, intellectually robust science-fiction films make a load of money.

And what happens after films likeEx Machinais that you see a wave of them being released. This could change becauseBlade Runner 2049bombed, and as a result I expect we could see fewer highbrow films in the coming years, but we’ll see. It’s show business. The next project that I’ve been working on is going to be on TV, it’s almost like companion piece toEx Machina, it’s sort of set in the same world – but you’ll have to wait for details.

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook,InstagramandFlipboard