Women in science is a hot topic. Plenty of women do science degrees, but progress to the upper echelons of science is not what it should be. In the UK, in the biological sciences – less so in the physical sciences – around half of undergraduate degrees are awarded to women. That starts to drop once you look at higher degrees and by the time you get to professor level, no more than 20 per cent are women.

The world of science should be accessible to everyone. Science underlies our daily lives and drives innovation and technological and medical advancements. In our book, Ten Women who changed Science, and the World (£13.99, Robinson), we’ve unravelled the life of 10 women in science, from a wide range of scientific disciplines. We’ve looked at how their background and environments inspired and influenced their approach to science, delved into what they discovered and shown how these discoveries have changed science, and the world.

Read more about inspiring women in science:

These were ordinary women who did extraordinary things, often in challenging circumstances, and sometimes, in the case of Marie Curie, killing her. Although her death from radiation sickness was an extreme example, working conditions were frequently tough.

Prejudice against women in science was a common feature and financial constraints, political and wartime circumstances are a constant theme too. Working in hiding in war torn Italy, Rita Levi Montalcini was forced to set up a laboratory in her bedroom. She undertook painstaking experiments that revealed the existence of a molecule, called nerve growth factor, which drives the development of the nervous system and is implicated in the development of diseases like Alzheimer’s.

With the help of her brother, ‘Rita found ingenious ways of assembling the necessary equipment. The chicken eggs were incubated in a homemade incubator – a box with a thermostat. Ordinary sewing needles, sharpened on a fine grindstone, became surgical tools for operating on the tiny embryos. The local watchmaker was a source of miniature forceps and an ophthalmologist provided micro scissors commonly used in eye surgery. Hidden away from the chaos of wartime and guarded by her mother, who dissuaded all intruders by declaring “she is operating and cannot be disturbed” Rita began to make full use of her microsurgery and histology skills.’

Rita never gave up in her pursuit of science and, like many of these women, drew on all her inner resources, including a strong streak of intuition. Dorothy Hodgkin who discovered the structure of important biological molecules like insulin was renowned for her sixth sense. Her work involved interpretation of complex X ray images. It often led her, and her alone, to recognise what the blurred patterns were trying to reveal.

Part of Dorothy’s success came from the sheer number of hours she put into her work but she was not totally welded to the bench. Dorothy understood the importance of fostering relations, both in her lab and in a much wider sense. At the height of the Cold War, she kept the lines of communication open between western and communist bloc scientists.

Closer to home, one of her visiting Indian colleagues remarked on his experience of working in Dorothy’s laboratory, saying, ‘The family visits to her home were another thing that contributed to our success. Not that we were talking about crystallography – but somehow you would come back and feel that you could do even better.’

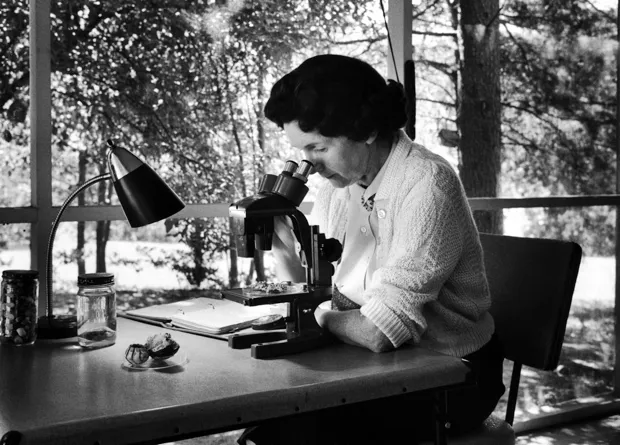

Family was important. And the environment in which they were brought up was a constant source of inspiration. Rachel Carson’s childhood rural idyll, threatened by smoke billowing from local industries, permeated her later environmental research and writing. Her passionate concern for the environment, and the damage man was doing to it, culminated in her most famous book Silent Spring, published in 1962. Her beautifully written books are credited with sowing the seeds for today’s focus on, industrial pollution, climate change and the state of our oceans.

Another featured scientist had her sights set on more distant worlds. Henrietta Leavitt discovered a way of measuring the distances between stars so that far more information could be obtained about the scale of our Universe. Her working methods and conditions were vastly different to those of Gertrude Elion in her chemistry labs, discovering new treatments for cancer, or Virginia Apgar, determining the five life-saving signs of a newborn baby’s health and wellbeing. But all these women shared a passion, focus and tenacious approach to their science.

The threads of their scientific lives – successes and failures - are woven into the history of scientific endeavour and the rich tapestry they created serves as a vivid reminder that the world of science is open to all, men and women.

Ten Women who changed Science, and the World by Rhodri Evans and Catherine Whitlock is available now (£13.99, Robinson)