Back in 1995, McArthur Wheeler robbed a Pittsburgh bank in broad daylight, armed with a gun. Bolstered by the success of his first attempt, Wheeler robbed another. Despite both banks being wired with security cameras, it seemed that Wheeler had made no effort to disguise himself, so police played the surveillance tapes on the 11 o’clock news.

Perhaps unsurprisingly to everyone but Wheeler, an informant recognised him and he was arrested later that night. When police showed him the footage, he was stunned. “But I wore the juice,” he mumbled.

Lemon juice can be used as an invisible ink that reveals a message when heated (the sugars in the juice turn brown). Wheeler had learned this and arrived at the conclusion that a squeeze of lemon on his face would render it invisible to the bank’s cameras, just as long as he didn’t get too close to any heat sources.

As surprising as Wheeler’s error of judgment was, his overconfidence might sound familiar if you’ve been following politics lately. High-ranking figures seem to consistently underestimate the difficulty of the task in front of them, such as the UK’s former Brexit Secretary, Dominic Raab, who stated he “hadn’t quite understood” how reliant UK trade is on the English Channel’s Dover-Calais crossing (2.5 million heavy goods vehicles cross every year).

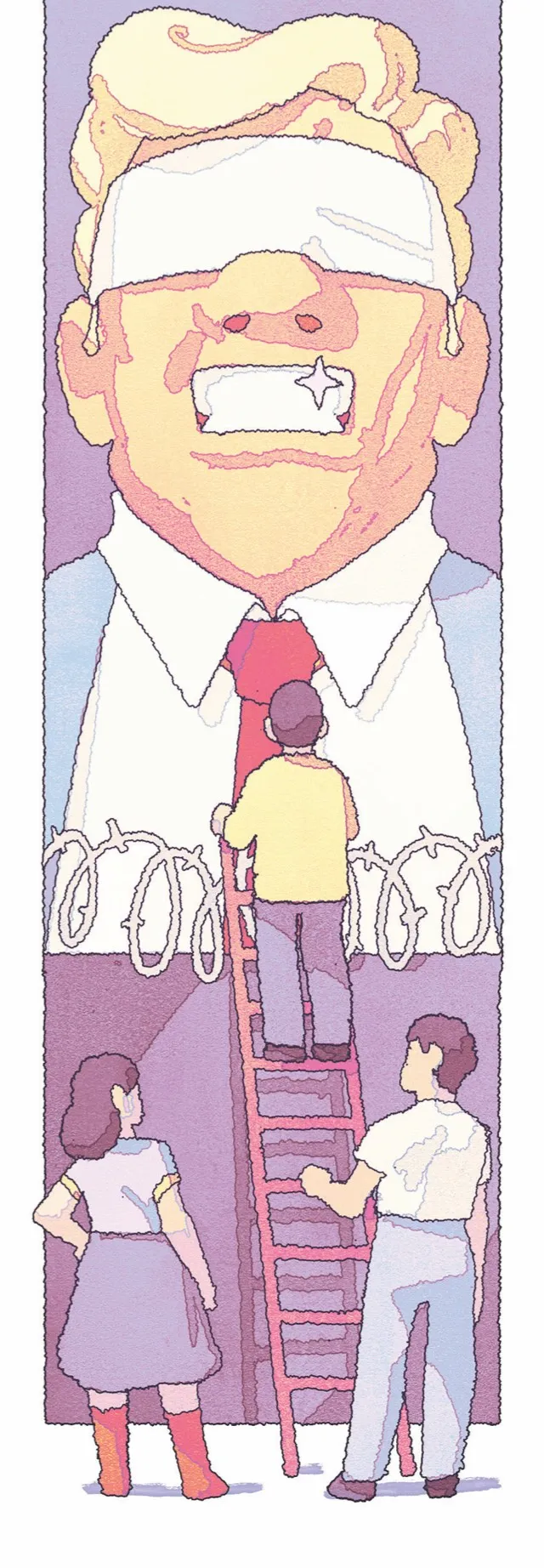

In the US, Donald Trump’s travel ban, initiated in 2017, caught border officials by surprise, leading to mass confusion about who to let in. It was a big move, spearheaded by a president underestimating the complexity of his aspirations.

On both sides of the Atlantic, and of the political spectrum, it’s become all too common to see the ascent of supremely confident leaders, who brush off mistakes with a charismatic smile. Whether they’re from the world of politics or business, these figures appear bulletproof, bouncing from one influential role to the next.

So what can the study of leadership psychology tell us about what’s happening, and why is it happening now?

The Dunning-Kruger effect: the incompetence double-burden

Inspired by Wheeler’s optimistic armed robberies, social psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger designed an experiment. They tested university students’ logical thinking skills, knowledge of English grammar and sense of humour, and then asked the students how well, or badly, they think they did.

All three tests supported their hunch: the students who performed among the worst had no idea how bad they truly were. “On average they were only outperforming 10 to 15 per cent of the people in our sample, but they thought they were outperforming 60 per cent. They were almost as confident as the people at the top,” says Dunning.

This phenomenon is now known as the Dunning-Kruger effect. It describes how the incompetent suffer a dual burden; not only are they bad at the task at hand, they’re so bad that they’re blind to their own ineptitude. As a result they enjoy an inflated sense of their own abilities and tackle tasks in a blissful state of overconfidence.

Two decades on, the Dunning-Kruger effect is being noted in worrying new areas.

A 2018 study across several American universities reported that extreme opponents of genetically modified foods know the least about science and genetics, while believing they know the most.

Another study published in 2018 surveyed 1,310 US adults about the causes of autism and whether or not it is linked to vaccinations. “A third of Americans say they know as much as doctors and experts,” says Dunning, who wasn’t involved in the study. “But that third is actually the most misinformed.”

Dunning himself sees the effect often among people in positions of authority, recalling the case of the Crystal River power plant in Florida. The company running the plant tried to cut costs by managing a complicated repair job themselves, which ended up creating more damage to the concrete shell of the building that kept the radiation from escaping.

One source put the estimated cost of the mistake at $3bn (£2.3bn approx). “You can see it in a lot of places in life,” Dunning says. “Unfortunately, you often see it after the fact.”

Confidence implies competence

In politics, it’s well documented that we gravitate towards confident, charismatic leaders. “People take confidence as a prime indicator of competence,” says Dunning. “You see that in the courtroom with which witnesses to follow. You see it in the office, in terms of which bosses to follow.”

Psychologists studying influence often talk about competence cues. These are signs that the person in front of us knows what they’re talking about, such as speaking opinions loudly and without hesitation.

We read body language and use it to assume competence, too, such as using emphatic gestures when making points and appearing at ease with tasks. Former prime ministers David Cameron and Tony Blair were both famous for their confident hand gestures. And numerous politicians, from both ends of the political spectrum, have been photographed in the “power stance”: upright with their legs spread exaggeratedly far apart. Body language experts have speculated that they’ve been advised to take up as much space as possible, another competence cue.

What makes confidence so appealing? Dr Sander van der Linden, a social psychologist at the University of Cambridge, describes the typical charismatic leader as someone who articulates an ideological vision, and tends to talk about distant goals more than near-term goals because they don’t have anything concrete to offer.

“They have very clear and simple ideas about how they’re going to overcome massive social problems with this grandiose vision,” he says. This fits across the Atlantic, too – Trump’s ‘Make America Great Again’ is a fine example of a grandiose but vague proposition.

In van der Linden’s lab, he studies how groups of people behave when faced with tricky tasks that require cooperation. “If I put some students together in a room and ask them to sort themselves out, what tends to happen is that students drift towards the person who’s confident, slightly aggressive and has a vision of what they’re supposed to be doing and how to implement it,” he says.

“Because that resolves a lot of cognitive complexity for people. Imagine you don’t really know what the task is, and somebody shows confidence and ability and they communicate in a simple way, and they seem to have everything figured out. It’s much easier to follow that person.”

The allure of confidence is understandable, and familiar, particularly when it comes to complex, messy problems. You can imagine being tempted to hand control over to the UK’s international trade secretary Liam Fox, given his confidence that “The free trade agreement that we will have to come to with the European Union should be one of the easiest in human history.”

Misattribution of mistakes

Unfortunately it seems that once a person has created a confident image of themselves, it’s a hard perception to shift. In reality, according to van der Linden, when you’re a confident leader you’re less likely to cop the blame when something goes wrong.

In 2004, researchers tested participants’ perceptions of President George W Bush, and discovered that those who found Bush charismatic were less likely to blame him for failures in the Iraq war. The researchers then created a “crisis condition” in which participants were alerted to a warning from the CIA that al-Qaeda was planning a terrorist attack in the US.

When encouraged to worry about terrorism, participants found Bush more charismatic and were even less likely to attribute blame to him. It’s a potent combination; a charismatic leader that makes us feel like we’re in safe hands, operating in a time of crisis.

Social and political crises can make us feel distressed, anxious and hopeless, so it’s understandable that in those situations we are drawn to leaders who promise to deliver better times.

Academics have recognised that Brexit is causing some UK citizens anxiety, creating what van der Linden calls a “charisma-conducive environment” in which we’re much more susceptible to charismatic leaders offering simple solutions.

In one slightly morbid experiment, published in Psychological Science in 2004, researchers asked participants to write down what they felt when they imagined their own death, and what they think will happen to them physically as they die.

With thoughts of their own mortality front and centre, 33 per cent of participants favoured a charismatic candidate in a hypothetical election, compared with just 4 per cent in a group who had not been primed to consider their own death.

In another experiment, participants were reminded of recent terrorist attacks and read an argument that similar attacks could take place locally. Those people were more likely to favour a charismatic leader, even when that leader was presenting political messages that conflicted with the participants’ own values.

van der Linden points to Germany in the 1930s as a clear example of citizens being susceptible to a charismatic leader in troubled times. “Leading up to WWII, where people were suffering, Hitler emerges as a grand leader with a new vision. Charismatic leadership, especially when it comes to advancing ideas that people otherwise wouldn’t readily accept, is more likely to occur when there’s fear, uncertainty and social unrest, which confirms what we see in experiments.”

Avoiding the pitfalls

It’s clear that making good collective decisions around who to elect isn’t getting any easier. The issues that matter, like climate change, healthcare provision, economic policy and unemployment have no simple solutions. That may have left people craving apparently strong leaders; ones that seem to have all the answers. So how can we instead ensure we pick capable leaders?

According to van der Linden, we shouldn’t ignore charisma altogether – just look for leaders with the right motivations. “Personally-driven, charismatic leaders [seek positions of power] because it offers control and influence. But we also have charismatic leaders that are collectively-oriented and egalitarian, who care about their followers and have the best for them in mind.”

Dunning says an antidote to the effect that he and his colleagues first described is to seek out the opinions of neutral experts: with expertise comes the ability to accurately judge the capabilities of those around you, even when expertise and intellectualism is attacked.

Dunning also notes that confidence has its place. “There are situations in which even unrealistic confidence is good, and situations in which unrealistic confidence is very, very bad,” he says. “In the preparation stage of things, you really want to be underconfident or obsessive. But on the day of battle you can’t really show doubt. It’s time to lead. You need to know where confidence works, and where it works against you.”

- This article was first published onBBC Science Focusin March 2019 - subscribe here.

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard