If you're going to be the best at winter sports you're going to need speed, skill, and a bit of science. Find out what givesthe world's top winter athletes the edge on the slopes.

Speed skating

Consisting of the 400m long-track and 111m short-track events, speed skating is sprinting on ice. Most athletes wear specially designed clap-skates with a hinge fitted at the front that allows the blade to stay in contact with the ice for longer. This means more power can be transferred from the leg into forward motion. Despite the awkward appearance, the aerodynamic skinsuits and low ice friction allow skaters to reach speeds of up to 70km/h, making them much faster than track runners.

How to win

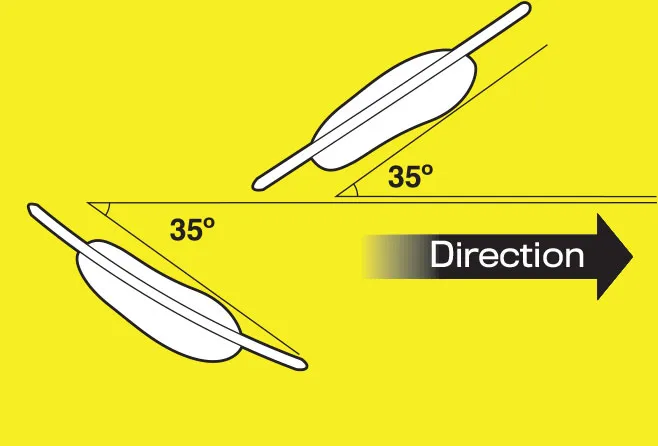

Skating is not running, and requires your feet to strike the ground differently. Skaters move fastest on the straight if they angle their blades about 35° from forward, and push out in sweeping strides. On a bend they should use short steps, like climbing stairs sideways.

Bobsled

In bobsledding, crews of either two or four careen down high-tech tracks in even higher-tech sleds. Acted on by gravity, ice friction, aerodynamic drag and high-g centrifugal forces, they can reach speeds of up to 140km/h (86mph). Margins are tight; just a few hundredths of a second can make the difference between glory and going home empty-handed.

How to win

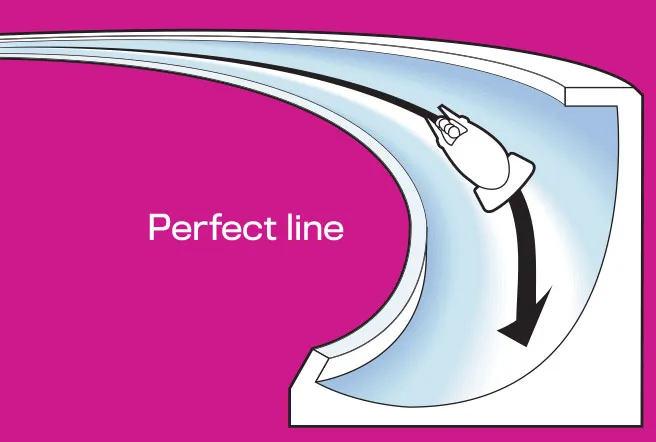

Successful crews feature heavy athletes, because added weight cuts the effect of drag force relative to gravitational force and muscle power is vital for a fast initial push-off. As it corners, the sled is thrown up the bank by centrifugal force. Here the driver must keep the sled close to the perfect racing line: too high and the distance travelled is increased, too low and the sled loses speed.

Curling

Players push 18kg granite ‘stones’ some 30m towards a target across ice. The ice has been pebbled by spraying it with water, which forms raised bumps upon freezing. The stone has a handle on its top that can be tweaked to make the stone spin as it slides down the ice. Its path curves to the right for a clockwise spin, and to the left for anticlockwise.

How to win

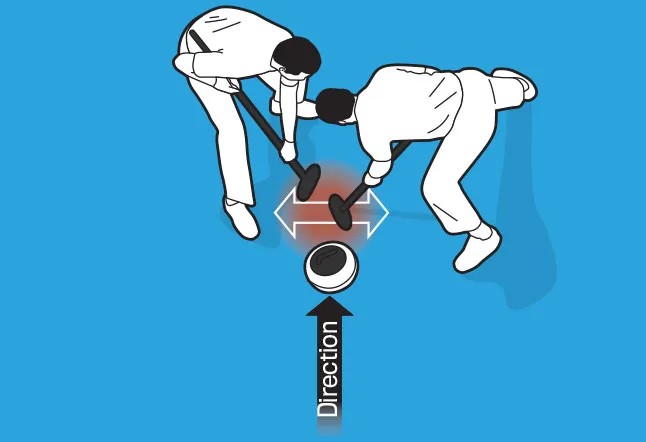

While the stones’ curling motion must be down to an asymmetry, physicists are uncertain how it occurs. The bottom of the stone – an annulus like on the bottom of a teacup – and the pebbling appear to be crucial. It may look odd but sweeping ahead of the stone is essential. The action reduces the friction by increasing the temperature and softening the ice, allowing the stone to travel longer.

Ski jumping

Ski jumpers soar through the air some 100m when launching off from a so-called normal hill, and 140m from a large hill (there’s also a more extreme version known as ski-flying, in which competitors can jump distances in excess of 200m!). The slope of the hill is carefully chosen so the skier is neververy high above the ground, and so can land softly.

How to win

Tucking into a crouched position during the initial run reduces drag. In flight, you maximise lift by leaning forward and forming a V with the skis. To win, you need to be light and lean to maximise lift-to-weight ratio. It’s also key to transition smoothly from the crouched, ‘egg’ position to a stable V-style flight profile.

Snowboard Cross

Four snowboarders negotiate a downhill course packed with ramps, twists and cambered turns. Their top speeds aren’t quite as fast as their ski-borne counterparts but with more close manoeuvring, jumping and airborne turning, snowboarding is all about controlling weight distribution.

How to win

Medal-winning snowboarders choose to jump more than they have to. This technique reduces drag, because travelling through air slows them down less than having to carve through the snow. The narrow course makes it difficult to overtake unless the leader falls. In the women’s snowboard cross event at Whistler 2010, Canada’s Maëlle Ricker won gold by not crashing all the way to the finish line after first taking the lead with a good start.

Giant Slalom

In this alpine event, skiers manoeuvre between poles as quickly as possible. The skiers are propelled downwards by gravity, but much of this energy is dissipated overcoming friction and drag. All manner of fancy ski waxes and slippery suits are used to minimise this effect.

How to win

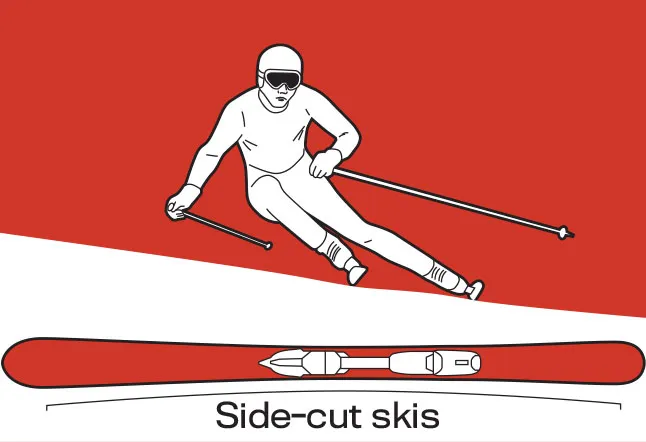

Ski design is very high-tech to minimise friction and make it easy to turn. Modern carving turns are facilitated by side-cut skis, which naturally turn when pressure is applied in the right place. This technique is much faster than the parallel turns used until the 1980s, when older straight-edged skis were used.

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard