The Orionid meteor shower has been steadily building throughout the month and could offer an early winter treat for stargazers. It’s one of two meteor showers associated with Halley’s comet: the other being the Eta Aquariids in May. The Orionids are easily identified by their fast speeds and are often considered as one of the most beautiful. They are by far the best shower since the Perseid meteor shower in August, especially since a full Moon somewhat scuppered viewing conditions this year.

So, what’s the best way to maximise your chances of spotting an Orionid? What causes the Orionid meteor shower? And, when exactly should you look up to see it?

If you’re keen to make the most of the longer evenings, make sure you check out our astronomy for beginners' guide and our full Moon calendar. For a full roundup of this year's meteor showers, we’ve got all the essentials listed in our meteor shower calendar.

When can you see the Orionid meteor shower 2022 in the UK?

The Orionid meteor shower began at the end of September and will be visible until around 7 November 2022. The number of meteors starts to rise sharply as we reach the peak on 21-22 October, and we should be offered relatively decent viewing conditions, thanks to a waning (shrinking) crescent Moon. The Moon itself will rise at 2:21am on 21 October and at 3:36am on 22 October.

The best time to view the Orionids in 2022, will be between midnight and sunrise (which occurs at approximately 7:34am) on the morning of Friday 21 October, and the same time on 22 October.

However, if you miss the Orionids at their peak, all is not lost. This meteor shower has a more sustained maximum than other showers, lasting for around a week centred on the peak, before tapering off as we head into November.

Where to look

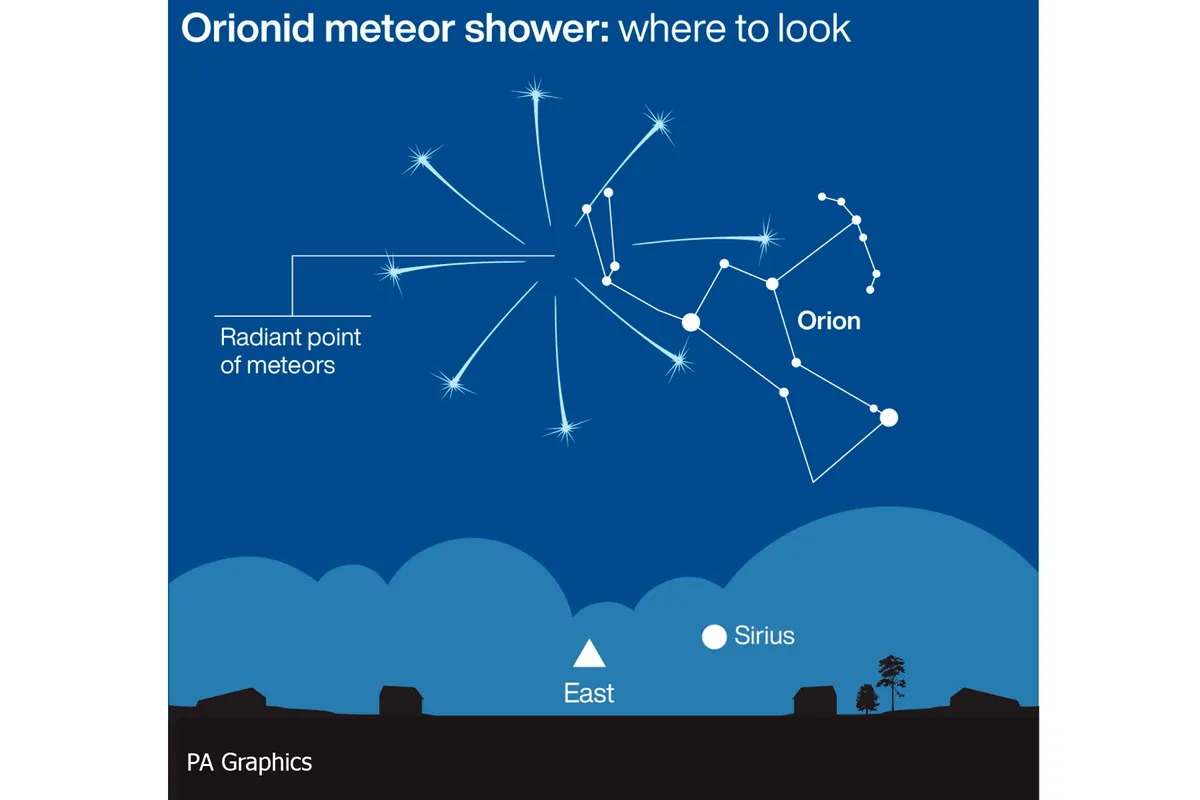

The Orionids are visible from both the northern and southern hemispheres. The radiant – the point in the sky from which the meteors appear to originate – as the name implies, is situated in the winter constellation, Orion.

However, you don’t need to restrict your viewing towards Orion; the meteors will be visible across the night sky. Looking away from the radiant will also give you the added advantage of potentially seeing ‘longer’ meteors, as opposed to the shorter meteors you might spot nearer the radiant.

This is due to something called ‘foreshortening’ – an optical illusion that causes a meteor’s train to look shorter, because it is angled towards us.

The radiant is easy to find, look towards the eastern horizon after midnight, and locate the three distinctive stars that make up Orion’s Belt: Alnilam, Mintaka and Alnitak. If you look slightly below Orion’s belt, keen eyes may even be able to spot a fuzzy patch; the Orion Nebula. The radiant itself, is at a point at the northwest corner of the constellation.

How many meteors will you be able to see?

The Orionids are known for their brightness and speed; these meteors are fast, which gives us certain benefits when viewing. Travelling at speeds of up to 66km per second (that’s 148,000 mph!), means that – weather permitting – we might be treated to glowing trails that persist for longer. Fast meteors also mean a slightly higher chance of seeing a fireball (an exceptionally bright meteor), although still rare.

At its peak on 21-22 October 2022, the Orionid meteor shower has a maximum zenithal hourly rate (ZHR) of around 20-25 meteors per hour. This figure, however, assumes perfect (or near-perfect) conditions: clear skies and no light pollution, as well as a radiant that is directly overhead. In 2007, a whopping 80 meteors per hour were reported.

Given that the Orionids have a relatively low-altitude radiant (i.e. the constellation Orion is still fairly low in the sky), it’s unlikely we’ll see this many. In reality, we can expect to see around 10-15 meteors per hour.

Where do the Orionids come from?

Like the Eta Aquariids in May, the Orionids are the result of debris from 1P/Halley, more commonly known as the famous Halley’s Comet.

Halley’s Comet itself is a crumbly, ‘dirty snowball’ comet, comprised of a mixture of volatile ices and dust. It’s been travelling around the Sun for at least 16,000 years, leaving a trail of debris in its wake. It has a highly elliptical orbit that stretches out around the Sun like an elongated oval, extending beyond the orbit of Neptune at its furthest point.

Every time Earth ploughs into this stream of dust from Halley’s comet, which it does twice a year, particles enter our atmosphere and disintegrate, leaving bright streaks in the sky that we see as meteor showers.

Viewing tips

If you can, find an area away from light pollution. Night temperatures on the 21-22 October are expected to be fairly mild, around 9 to 11°C with a light cloud and low chance of precipitation in London – but remember to check your local weather forecast. Even so, be sure to wrap up warm, as you’re probably not going to be moving around much.

Lie back in a reclining chair, hammock, or on a blanket, and let your eyes adjust to the darkness for around 10 to 20 minutes.

After a while, and with a little patience, you’ll find your eyes become more accustomed to seeing the meteor trails as they streak across the sky. Try not to look at other bright sources of light (such as your phone) during this time. If you do, use a red filter. This is because the rod cells in our eyes are not sensitive to red light, and therefore it doesn’t interrupt the accumulated night vision. Many astronomers use red light torches and filters for this reason.

Read more: