Every living thing has to eat somehow… whatever type of mouth it might have. And there are some truly bizarre mouths in the animal kingdom. Some of the most extraordinary examples are enough to leave you slack-jawed.

Unfussy eater

Striped macekrel

Most animals are relatively picky eaters, preferring only plants or only meat, and tend to rely on one strategy when foraging or hunting.

Mackerel are unusual because they use two different ways of feeding, filter-feeding and particulate feeding, and opportunistically switch between them whenever it makes sense. Particulate feeding involves catching each prey item individually, like a shark or penguin would.

Filter feeding is how bivalves and baleen whales eat and involves straining pieces of food out of the water. Mackerel use the underside their gills, which have overlapping bony hooks called gill rakers,

as makeshift sieves to capture prey suspended in the water.

All fish have gill rakers and variation in their appearance is sometimes used to identify different species. When prey is small and numerous, like a swarm of plankton, filter-feeding gets the most food for the least effort.

For large or sparse prey, particulate feeding is better. By not being too picky about how they get their meals, individual mackerel keep their bellies full, even when surrounded by thousands of other fish in a school.

Rapid inflation

Gulper eel

Food is scarce in the deep ocean, so animals living down there have to make every meal count. Few animals take this as seriously as the gulper eel, which is also known as the pelican eel as it shares a similar characteristic with the bird.

The gulper eel has a huge, loose-hinged mouth that’s about a quarter of the length of its body. The mouth is paper-thin, fragile and unwieldy, so the eel tucks it away when it’s not feeding. Gulper eels have long, whip-like tails, but aren’t fast enough to chase down their prey.

Instead, they float and wait, camouflaged by the darkness of the deep ocean. When a school of crustaceans or squid approaches, the eel lunges forward, rapidly unfolding its origami mouth to take a huge gulp of water.

After the attack, with its mouth fully inflated, the eel looks silly, like a lollypop or a balloon. It then slowly pushes the extra water out through its gills before swallowing the unlucky prey

trapped in this signature feature.

Bottom feeder

Sea urchin

A sea urchin’s mouth is on its underside, and that’s probably the least bizarre thing about how it eats.

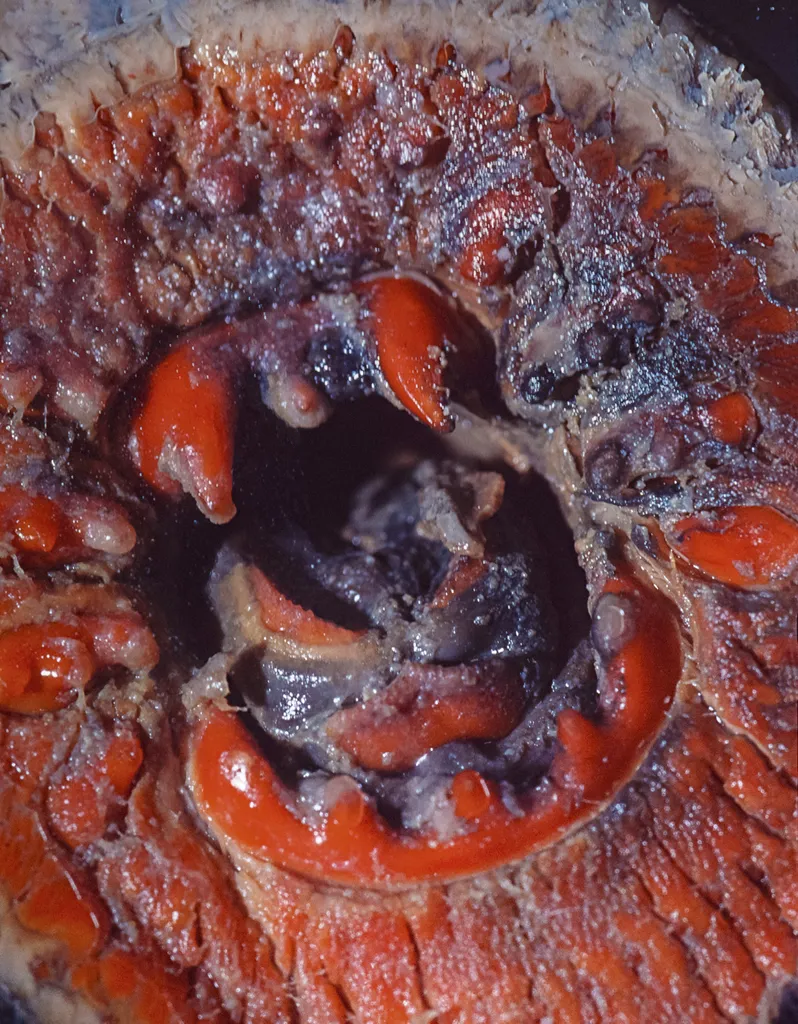

Inside the sea urchin is a complex, pyramid-shaped structure made of calcium carbonate, a hard chalky

material also found in coral.

The pyramid is made of several triangle-shaped plates, each with a hook-shaped tooth at the tip. Like a claw machine you might find at an old arcade, the pyramid can move up and down, and tilt. It can also move each plate to scrape, grasp, burrow and even grind rocks.

The individual plates are sharpened as they slide against each other, so they’re always ready to cut. The whole apparatus is precisely controlled by a network of wiry muscles. Aided by their powerful jaws, sea urchins feed voraciously – a single colony of these spiky relatives of sea stars can destroy an entire kelp forest by chewing up rocks and uprooting seaweed.

The urchin’s biological claw machine, properly called Aristotle’s lantern, is so unique that it’s inspiring engineers to design new machines to scoop up soil samples on Mars.

The ultimate underbite

Cookiecutter shark

Back in the 1970s, several submarines belonging to the US Navy returned from missions with damaged sonar equipment. Initial fears of a new enemy weapon dissipated once the culprit was identified: the cookiecutter shark.

Cookiecutter sharks, as their name suggests, leave perfectly round cut-outs in large fish and marine mammals (and the rubber covers on subs’ sonar domes). These parasites make their living through stealth and subterfuge, hovering in the water until something big and tasty approaches.

They sneak up and latch on with their fat, fleshy sucker lips. The sharks anchor themselves into place by

digging in with their narrow upper teeth while the razorsharp teeth in their lower jaws slice into the flesh. They twist and spin, moving their lower jaws back and forth like a bandsaw, carving out a perfectly round disc of meat before slinking back into the gloom of the deep sea.

Cookiecutter sharks are harmless to humans and little more than a pest to their huge prey, but still pose an occasional nuisance to ocean operations by damaging unprotected equipment and telecommunications cables.

Monster mouth

Lamprey

Several Hollywood creatures, including the sandworms from Dune, the kraken in Pirates of the Caribbean and the sarlacc from Return of the Jedi, have a stylised version of a lamprey’s mouth. There’s something extremely unsettling about concentric rings of sharp teeth leading into the black depths of a monster’s throat.

Real-life lampreys are evolutionarily ancient animals that split off from the rest of the vertebrates over 500 million years ago – before the evolution of jaws and bone. Using a combination of suction and hooks made of keratin (the protein your fingernails are made from), a lamprey can latch onto large fish, whales or even sharks.

Over the course of a few days, the lamprey burrows into its victim’s flesh with a sharp, rasping tongue that works like a piston, engorging itself on blood and fluids. The frightening appearance and unsavoury lifestyle of lampreys gives them a bad reputation.

In reality, they’re important members of the ecosystem: lamprey larvae filter water and sediment in rivers, like bivalves, and are an important food source for bottom-feeding predators, such as sturgeon.

Platefuls of food

Humpback whale

Humpbacks only eat from spring to autumn during their holidays in the prey-rich waters of the Arctic and Antarctic. With such big bellies to fill and a limited time to do it, they rely on an ingenious strategy known as ‘bubble-net hunting’ to get the job done.

Often working in a group, humpbacks dive below their prey, then slowly ascend towards the surface in a spiral, blowing bubbles as they swim up. The bubbles scare and confuse their prey of small fish and shrimp-like crustaceans called krill.

The whales make tighter and tighter turns, aided by their long flippers, concentrating their future meal into a dense cluster near the surface. Eventually, they take turns lunging up, mouths open, through the compacted prey, gulping tens of thousands of litres in a single mouthful.

The whales push the water out of their mouths, filtering it through the sieve-like baleen plates on the roofs of their mouths. The fish or krill are trapped in the strong but flexible bristles, ready to be swallowed whole by the hunters.

Read more:

- Meet the fearless scientists saving Antarctic whales… With crossbows and tiny inflatable boats

- How humpback whales communicate through a hidden global network of song

Saw throat

Leatherback turtle

Leatherback turtles spend most of their lives in the open ocean, tracking their prey into the depths during the day and into the shallows at night. They’re always looking for jellyfish, their favourite food, though they’ll occasionally snack on other soft treats, such as squids or small crustaceans.

Leatherback turtles eat so much jellyfish – hundreds of kilograms per turtle per day – that they act like natural pest control, keeping jellyfish populations in check and protecting larval fish and beaches from nuisance swarms.

Jellyfish are squishy and not the easiest thing to pin down, especially if you don’t have any teeth or claws. Leatherback turtles snip jellyfish into digestible pieces with delicate, scissor-like jaws. What’s more, the throat of a leatherback turtle is lined with backwards-pointing spines, which stop its slippery prey from escaping once caught (jellyfish can survive being cut in half, after all).

The spikes probably also provide some protection from the stinging cells of their prey, as leatherback turtles can even eat poisonous creatures such as the jellyfish.

Nutcracker

Pacu fish

Say cheese! Pacu fish have a mouth full of flat, square teeth that gives them a human-like smile. Sometimes referred to as ‘vegetarian piranhas’, due to their body shape and colouration, pacu fish prefer to snack on freshwater ‘trail mix’ instead of fresh meat.

Their molar-shaped teeth do an excellent job of crushing the hard shells of the nuts and seeds that frustrate other animals, providing them with a reliable source of fat and protein despite their plant-based diet. Pacu fishes are the gardeners of the Amazon and play an ecologically important role in spreading seeds throughout the river’s tributaries and floodplains.

The most famous of the pacu fishes, the tambaqui, can get as big as a golden retriever. At one metre in length (3ft) and weighing 30kg (66lbs), it’s the second largest fish in the Amazon (after the arapaima).

Tambaqui are a popular meal in South America, where it’s often sold with cuts on the bone like pork ribs. They also show up in the exotic pet market, though they need an experienced keeper and a truly enormous tank to thrive.

Cat got your tongue?

Penguin

Penguins are agile predators underwater, zipping around like torpedoes as they chase down fish

and squid. But how do they keep their prey from squirming out of their grasp? The answer lies in what

the birds already have in their mouths.

A penguin’s mouth and tongue are covered in hard, backward-pointing spines called papillae. It’s the same feature that makes a cat’s tongue feel like sandpaper. But you wouldn’t want a penguin to lick you – the spines aren’t just large, they’re also sharp (a lick from one of these would easily make you bleed).

The spines dig into slippery prey and help move it down the bird’s throat. A penguin’s tongue is also very muscular, so is probably used to push and manipulate the food in their mouths, like humans. Unlike us, however, penguins can’t taste the fish they eat, as they don’t have the genes to register sweet, bitter or savoury (umani) flavours.

Scientists think that penguins lost their sense of taste because they don’t use it: not only do they swallow their food whole, but the proteins needed to send taste signals to the brain malfunction at cold temperatures.

Read more: