Total solar eclipses in and of themselves are pretty weird. By a twist of fate, the Sun, which is 400 times larger than the Moon, happens to be 400 times further away, meaning that the entirety of the Sun can be engulfed by the passing Moon.

That’s what’s going to happen come 8 April across North America if you’re lucky enough to live in, or be able to travel to, the so-called ‘path of totality’ – where the Sun and Moon will align perfectly.

To accompany the weirdness of the total eclipse itself, a bunch of strange phenomena are expected to ensue. Keep your eyes and ears out for these 10 bizarre happenings on 8 April.

1. Radio signals get messed up, and we don’t quite know why

While many of you are gazing up (with appropriate protective eyewear) to marvel at the eclipse, hundreds of scientists and amateurs will be busy bursting out radio waves and measuring how they’re affected.

We know this much: during an eclipse, a reduction in radiation from the Sun and a cooling of the atmosphere causes fluctuation in the upper layer of the atmosphere known as the ‘ionosphere’.

Radio waves, particularly those travelling long distances, often bounce off this layer on their way to the receiver. So, an eclipse can have a significant impact on how they travel.

All the data the radio enthusiasts collect will be poured over by researchers to understand how the ionosphere was affected, which could have important applications in military and disaster scenarios.

undefined

2. You’ll see the best ‘sunset’ of your life

No matter how many times you’ve seen a sunset, they’re always a joy to witness. But this one might just eclipse (pun intended) them all.

During totality, it gets dark, but not completely. In every direction – all 360 degrees – you should be able to see those classic sunset hues sticking to the horizon.

Of course, this is technically not a sunset at all, as the Sun is still high in the sky. The orange, pink and reddish colours are caused by sunlight from areas outside the path of totality, giving the illusion of a sun that has just dipped below the horizon.

3. Animals get seriously confused

Understandably, animals don’t have a clue what’s going on during a total solar eclipse. After all, the entire Sun just disappears, right in the middle of their day.

But animals all react differently to eclipses and research into this is few and far between by nature of the rarity of the event.

Dr Adam Hartstone-Rose led a study into animal behaviour at a South Carolina zoo during the 2017 eclipse. He tells BBC Science Focus that most animals begin behaving as if it's night time, while others become visibly anxious.

Some species, however, exhibit some seriously strange behaviour.

“It turns out that Galapagos tortoises had a remarkable reaction,” Hartstone-Rose says. “Right at the moment of totality, they started mating behaviour. As in, they literally started breeding in front of everybody, before our eyes.”

4. Stars and planets become visible during the day

Suddenly, and without warning, some of the brightest stars and planets will become visible as totality begins. It won’t be quite as dark as during the night, but you should be able to catch a glimpse of the following:

- Jupiter – the largest planet in our Solar System – will appear about 30 degrees to the upper left of the Sun.

- Venus – our closest planetary neighbour – will likely be the brightest object in the sky. It will be visible about 15 degrees to the lower right of the Sun.

- The stars Rigel and Betelgeuse will appear in the south-eastern sky.

Read more:

- How a solar eclipse revealed the warping of spacetime and opened a new window into the Universe

- How far apart are the Sun, Moon and Earth during eclipses?

- Why are solar eclipses rarer than lunar eclipses?

5. If you’re lucky, you’ll see a corona rainbow

Most people will be on the hunt for clear skies on the day of the eclipse, but a little bit of cloud cover might inject an extra bit of magic into the event.

The corona is the outermost part of the Sun’s atmosphere, usually hidden by the bright light of the Sun’s surface, that becomes visible during a total solar eclipse. It’s actually much hotter than the Sun itself, at one to three million – yes, million – °C. The Sun’s surface, meanwhile, is a lowly 5,500 °C.

Usual rainbows form when sunlight passes through water vapour in the air and is scattered into its constituent colours.

The same process can occur with light from the corona, meaning you get to see a dazzling array of colours, rather than boring old white.

So, pray for some light drizzle and a break in the clouds just at the right moment and you might catch a glimpse of this rare sight.

6. Mysterious ‘shadow bands’ will appear

In the last-gasp moments before totality, strange bands of shadow will trickle across plain-coloured surfaces. They’re kind of thin and wavy ripples of light and dark, much like the shadows you see on the bottom of a swimming pool.

Not everyone will see the bands, and scientists aren’t exactly sure what causes them, although it’s thought the turbulence of the Earth’s atmosphere plays a part.

If you’re desperate to observe this eerie phenomenon, lie a white sheet out on the floor and keep an eye on it in the minutes leading up to totality.

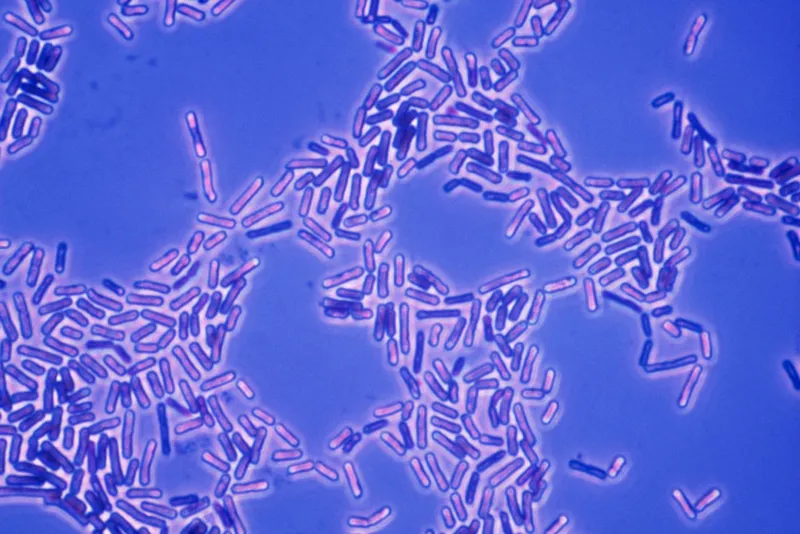

7. Microbes get muddled

It’s one thing for animals to start acting up during an eclipse, but who would have guessed life on the smallest scales can be affected too?

A 2011 study in India assessed how bacterial and fungal colonies responded to the environmental changes that occurred during an eclipse. The researchers found that the species changed shape and got smaller during the peak of the eclipse.

The immediate drop in sunlight also appeared to favour species that could acclimatise faster to the rapidly changing environment.

8. The wind will change direction

Something strange goes on with the wind during an eclipse, a phenomenon that has been observed for centuries and yet was only really explained in the last decade.

Unimaginatively named ‘eclipse wind’, the wind is known to drop in speed and shift direction significantly as the Moon blocks out the Sun’s light. This happens during partial eclipses too.

During the partial eclipse witnessed in the UK in 2015, researchers decided to figure out what was going on.

“As the sun disappears behind the moon the ground suddenly cools, just like at sunset,” says Prof Giles Harrison, who co-authored the study into eclipse wind.

“This means warm air stops rising from the ground, causing a drop in wind speed and a shift in its direction, as the slowing of the air by the Earth’s surface changes.”

9. It will suddenly get chilly

Bring a jacket with you if you’re planning to observe the eclipse – things can get a little cold fast.

Typically, you can expect the temperature to drop by around 5 °C when you enter into the Moon’s shadow, but there have been more extreme drops recorded in the past.

According to the Gettysburg Republican Banner, the temperature fell by as much as 15 °C during a total solar eclipse on 9 December 1834. Meanwhile, on 20 March 2015, when an eclipse swept across the Norwegian Island of Svalbard, temperatures plunged to a more-than-a-bit-chilly -21 °C. Brrr.

The temperature change is similar to that which occurs when night time rolls around, only weirder because it happens instantaneously.

10. Baily’s beads

Named after the English astronomer Francis Baily, the beads are an arc of bright spots, almost like twinkling diamonds, that appear around the edge of the Moon as it slides in front of the Sun.

The beads are formed as light from the Sun pierces through gaps between mountains and valleys on the Moon’s surface. The illusionary effect is a string of beads lining the Moon’s edge.

About our experts

Giles Harrison is a professor of atmospheric physics in the Department of Meteorology at the University of Reading. He is also a visiting professor at the Universities of Bath and Oxford. In 2016, Harrison was awarded the Institute of Physics Appleton medal and prize for his contributions in the field of atmospheric electricity, including the discovery of new global-scale atmospheric interactions, and his public outreach on the meteorological effects of the solar eclipse of 2015.

Adam Hartstone-Rose is a professor of biological sciences at North Carolina State University. His research typically focuses on anatomical adaptation in live animals (e.g., feeding experiments), examination of muscles (e.g., the muscles of mastication), and analysis of bones and teeth. In 2017, he led a study into animal behaviour during a total solar eclipse at Riverbanks Zoo and Garden in Columbia, South Carolina.

Read more: