In spite of the many stories that attest to bloodlust – a violent response to the sight, smell or taste of blood – there is no evidence for this phenomenon.

Where do these tales come from? In my research, I have found three explanations

- The magical belief that blood is a medium that brings us into contact with a supernatural world and which demons can use to drive us to insanity.

- The “evolutionary” idea that bloodlust is a prehistoric remnant of our struggle for survival in a violent past.

- The aesthetic view that pleasure can be derived from what is actually repugnant and fearful.

These cultural beliefs continue to inspire the myth of bloodlust up to the present, but why do they persist?

Can humans identify the smell of blood and does this smell make us aggressive?

In a series of experiments, we asked subjects to discriminate blood from red control liquids in different settings. While we are excellent detectors of pig’s blood, our ability to detect human blood is much less developed.

Incidentally, differences in sense of smell and one’s personal experience with blood had no effect on blood detection.

As we turned out to be poor blood detectors, we might expect that smelling human blood does not incite our combativeness in an aggressive context.

In a later experiment, we confirmed that sniffing real blood, fake blood, or just water while playing a violent computer game did not affect the players’ heart rate, skin conductance, or respiration rate in a significant way.

Interestingly, when we told the gamers that some “pheromones” were dissolved in the blood, skin conductance level and game scores dropped, irrespective of whether they smelled real human blood, film blood or water.

This finding suggests that blood contact, or more precisely, our mental imagery about blood, inhibits rather than boosts feelings of excitement, aggression, or anger.

Recent research showed that a mammalian blood odour component, E2D, which we identify as the typical “metallic” blood odour quality, functions in humans as an alarm cue that warns of impending danger.

Once subjects inhaled two long puffs of this chemical cue, they tended to lean backwards on an approach/avoidance test. In contrast to predators like wolves or tigers, humans do not seem to be attracted by E2D-odours.

Although participants did not associate the inhaled substances with blood, E2D activates a flight rather than fight response.

The weak concentration of E2D in human blood probably explains the unsuccessful detection of human blood in our first experiment.

That’s why humans do not make good vampires!

Are menses toxic, and do “menotoxins” really exist?

Top of the list of blood-related myths is undoubtedly the belief that menstrual blood is poisonous.

Most people scoff at this nonsense, but less known is how this dubious idea preoccupied so many serious scientists during the last century.

Dozens of researchers hoped to find the mysterious “menotoxins” that could explain why ham failed to cure, dough to rise and flowers and plants to grow, even photographs to develop.

As late as 1975 one researcher remained extremely optimistic, saying, “the possibility that menstruating women can, in certain cases, have a harmful effect on living organisms cannot be excluded”.

Menstrual blood could not be normal blood – an ordinary chemical substance that obeyed the laws of nature – but instead, it contained a certain magic, no matter how harmful it could be.

Read more about blood:

- Could I live as a vampire by just drinking blood?

- Can we make artificial blood?

- Who really discovered how blood circulates?

- Does microgravity affect menstruation?

The discussion was not settled one way or another, but simply died out due to lack of renewed interest and stimulating hypotheses and, of course, inconclusive results.

An old-fashioned urge for magic thus faded away.

What is haemothymia and is it real?

Bloodlust was an unquestionable phenomenon to 19th-Century physicians. Evolution theory – or a simplified version of it – predicted that humans would behave like wild predators once blood flowed.

Contact with blood changed an angry mob into a sadistic crowd and uninhibited hesitant soldiers into brutal fighters.

However, in some individuals an obsession for blood was sexually motivated. Psychiatrists coined this disorder haemothymia, though others called it mania sanguinis or folie sanguinaire.

In 1909 the English physician Thomas Claye Shaw lectured to the Medico-Legal Society in London about the neglected role that haemothymia played in murder.

Read more about psychology:

- Hallucinations: the many ways we experience things that are not there

- Consciousness: how can we solve the greatest mystery in science?

Blood did not have the same effect on everyone, Clay Shaw admitted, but in some people it had a sexually arousing effect.

Although his colleagues expressed doubts that bloodlust was a prominent motive for murder, they all agreed that the smell and sight of blood applies a certain effect.

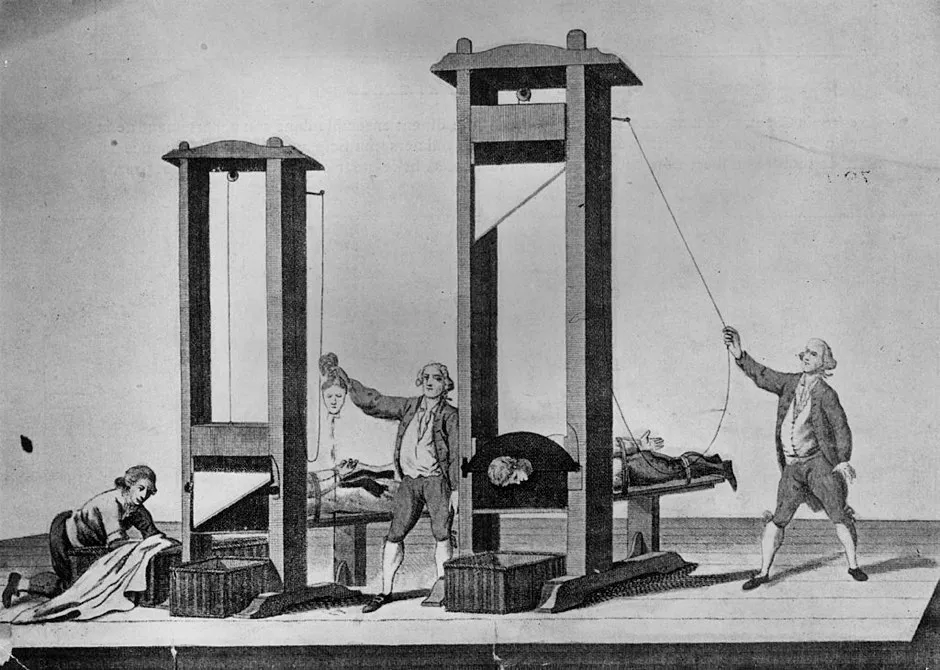

The bloody scenes of the guillotine inflamed the passions of the crowd during the French Revolution. No recent cases of haemothymia are known and although there are tales about child soldiers who become addicted to blood, a sexual motive is missing.

Blood Rush:The Dark History of a Vital Fluid by Jan Verplaetse is out now (£15, Reaktion).