Back in March 2016, Hillary Clinton’s campaign chairman John Podesta accidentally clicked on a ‘phishing’ link, allowing Russian-affiliated hackers to access his emails. It was the latest in a series of successful attempts to infiltrate the National Democratic Committee’s systems and discredit Clinton’s campaign. By the end of the same year, these breaches had become the centre of an international outrage and Republican candidate Donald Trump had been elected as president.

It took two years to prove the hacks on the National Democratic Committee were the result of foreign actors’ attempts to influence the US election. But finally, in 2018, an indictment was issued against 12 members of GRU, the Russian intelligence agency, alleging they took part in a “sustained effort” to hack the Democratic Party’s systems during the 2016 presidential campaign.

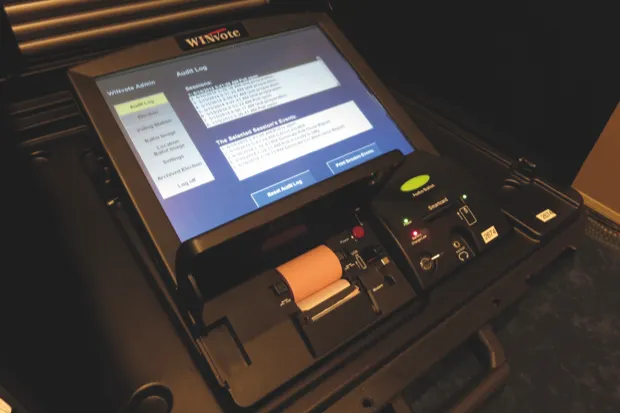

The US is determined to stop election hacking, but this will be a challenge, partly because nearly every model of its electronic voting machines is vulnerable to hacking. The issue lies in the fact that many of the machines lack robust security because they were not built to be connected to the internet – and those that do include security measures possess glaring holes.

The ease with which electronic voting systems can be manipulated was proven at the Def Con cyber security conference in 2017, when democracy-tech researcher Carsten Schürmann used a vulnerability to gain remote access to a WinVote machine within two minutes. During the same conference in August 2018, two 11-year-olds managed to hack into a replica of Florida’s election results website in under 15 minutes, changing names and tallies.

All this has proven that moving voting online is risky. But it hasn’t stopped countries offering people the chance to cast their votes electronically, rather than using traditional paper ballots. Estonia has offered online voting for more than a decade, with citizens proving their identity through state-of-the-art electronic ID cards. Yet even this method isn’t infallible: in 2017, scientists found a security flaw in the cards that would allow a potential attacker to steal someone’s identity.

Other attempts at online voting have been abandoned due to cyber-security fears. Norway tested online voting during parliamentary elections in 2011 and 2013, but this was discontinued after political disagreement and voter concerns.

In the UK, the election system is designed so it does not lend itself to electronic manipulation: voting and counting of ballots are “manual processes conducted under the watchful eye of observers”, says Dr Ian Levy, technical director of the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC).

Foreign actors

In contrast, the US uses electronic voting machines to allow citizens to vote. But these machines are often based on outdated operating systems such as Microsoft’s Windows XP, which are too old to receive security updates and, as a result, particularly vulnerable to hacking.

Weaknesses such as these are an easy target for the foreign and domestic actors interested in hacking elections. And although there is no solid evidence of successful attacks on online voting or counting systems yet, experts say it is only a matter of time.

“We can make a system that is end-to-end secure, but if it’s then layered on top of something insecure, a hacker will look for the lowest hanging fruit and it won’t make any difference,” says Professor Robert Young, of Lancaster University.

Adding to this, hackers are taking steps to understand the weaknesses in electronic voting machines. “Lots of machines find their way onto the second-hand market,” says Rodney Joffe, a former cyber-security adviser to the White House. “This gives a potential attacker the opportunity to experiment at will.”

Other election hacks are designed to influence voters or to undermine public confidence in the polling process. Attackers will combine breaches of physical systems with tactics such as fake news and disinformation, which were used by would-be hackers during the recent French and German elections.

Hackers will try to create doubt, even if they don’t modify anything. They could do this, for example, by manipulating the electoral roll.

The electronic poll books used in place of the paper rosters of registered voters are at risk of attack, says Joseph Lorenzo Hall, chief technologist at the Centre for Democracy and Technology in Washington. This could see hackers erase or change data, potentially stopping people from being able to vote.

More generally, he also expresses concern about cyber-attacks such as denial of service, where hackers flood election websites with traffic to make them unusable. “This affects people’s faith in systems.”

Securing elections

Several companies and organisations are already taking steps to secure elections. Matthew Prince is CEO of Cloudflare, which offers cloud services to government bodies at no cost to protect election infrastructure. The firm protects all parts of election security outside of voting booths, such as registration sites.

Another suggestion for securing elections gaining traction in the European parliament is blockchain – a list of records linked together using cryptography. The technology is widely known as the basis for cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, but it can be used in other ways too.

“People get excited about blockchain because it can create locked-down data that is difficult to change,” says Catherine Hammon, digital revolution knowledge lawyer at Osborne Clarke. “You can set things up, in theory, so no one can see who you are and how you voted.” This method is being tested to secure elections in several countries. In March 2018, when Sierra Leone’s presidential elections took place, votes in the Western Districts were registered on a blockchain ledger by Swiss-based firm Agora. Voters still marked paper ballots, which were then manually re-coded and uploaded onto a blockchain network. Meanwhile, an interesting trial is currently taking place in West Virginia in the US. First conducted during the 2018 Primary election in Monongalia and Harrison Counties, the pilot allows military personnel and their families stationed overseas to cast an official ballot using a smartphone app.

The app, developed by a start-up called Voatz, employs blockchain technology to ensure that once submitted, votes are verified and stored on multiple, geographically-diverse servers. The initial trial was a success and it’s currently being rolled out to all of the state’s 55 counties to be used in the mid-term elections.

Quantum mechanics can be used to prove identities

It offers potential for the future, but observers point out there are still problems with blockchain-based election security. “It won’t stop someone holding a gun to your head to force you to vote a certain way,” Hammon says.

It is also difficult for the technology to verify potentially hundreds of millions of voters in the time required. Hammon cites the example of the UK Brexit referendum, in which over 30 million people voted. “If blockchain verifies in seven seconds, the vote could take up to 55 days depending on the structure used.”

Other innovative security measures have also been suggested. Some think the answer to securing online voting lies in quantum systems, which could provide a way to produce truly random prime numbers – a key challenge in secure internet transactions.

Quantum key distribution – a method of secure communication using laser beams to transmit cryptographic keys – was used to send the results of Swiss elections securely from local centres to the State of Geneva’s central data repository. Prof Young, who has been working on applying quantum mechanics to cyber-security, says quantum key distribution can help by detecting people interfering with communications.

Proving identities

More generally, quantum mechanics can be used to provide identities. Known as atomic fingerprinting, quantum mechanics can be used to magnify the effect of imperfections in devices. “This allows us to ‘fingerprint’ them for identification and authentication,” says Prof Young.

Embedded within any electronic device such as a processor, these could be used in a simple way, to prove the authenticity of a voting machine when it communicates the votes cast back to the main server. “This could be used in tandem with quantum key distribution to also guarantee that the communications haven’t been altered or eavesdropped upon,” Prof Young adds.

At the same time, quantum mechanics can be used to generate numbers for creating cryptographic keys. Current systems tend to generate random numbers poorly, making cryptographic keys predictable so it’s possible to hack communications. “Most communication protocols use random numbers to create cryptographic keys and we can apply quantum mechanics to generate these more effectively,” says Prof Young.

But he admits there are major challenges when using quantum systems to secure elections, including the feats of complex engineering needed to ensure systems behave as they are supposed to. In addition, the quantum systems are very expensive, costing up to tens of thousands of pounds, so it’s not feasible to simply place them inside voting machines.

In reality, securing elections, at least in the short term, could come down to just a few simple processes. David Forscey, policy analyst at America’s National Governors Association thinks there are ways to improve security dramatically, without the need to implement “exotic solutions” that rely on quantum computing or blockchain. It can be as simple as updating old software or mandating that election officials use physical authentication keys such as USB tokens to log into their computers, he says.

Meanwhile, Marian Schneider, president at non-profit organisation Verified Voting, advocates a multi-layered approach to securing elections. “You need various tools to protect assets,” she says – including monitoring devices, firewalls and the ability to recover information when something happens.

Most experts agree the answer to securing electronic voting machines involves a back-up option, just in case things do go wrong. And right now, the safest solution is a voter-verified paper ballot – a paper audit trail of all votes cast electronically. Online voting is a good idea in theory, but it also opens up more doors to attack and manipulate elections. In the future, that isn’t going to change, which leaves the onus on security experts to ensure they stay one step ahead of the hackers.

- This article was first published in October 2018.

How a wall of lava lamps is helping to secure elections

Cloudflare is using lava lamps to create random numbers for the cryptography that underlies its election security offering. “When you visit a website and a lock appears on your browser, it’s there through a cryptographic process that exists by being able to generate a random number,” says Matthew Prince, the firm’s CEO and co-founder.

But computers are bad at the ‘randomness’ important in cryptography, he says. “If that number is predictable in some way, an attacker can undermine the cryptographic system itself.” To overcome this, Cloudflare uses physical solutions doubling as art installations to generate random numbers.

In the San Francisco office, the installation is a wall of 100 lava lamps (below). “The movement of lava in the lamps is impossible to predict – it’s a chaotic system,” says Prince. “We film the lava lamps and any pixel that changes can be used as a source of randomness. We then feed this into the system generating random keys for all of Cloudflare’s network.”

In the London office they use a double pendulum. “Anything unpredictable can be a good source of randomness,” says Prince.

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard