"Well, a Tornado is your old push-button phone with the antenna coming out, whereas the F-35 is your iPhone.”

Jim Beck is the station commander of RAF Marham in Norfolk, UK. Clearly identifying my scrambled brain, he’s breaking down into the baldest terms just what a revolution the Royal Air Force’s new F-35 Lightning II jets – which live at his base – represent.

“This jet fuses all the data it receives together and only presents about 1 per cent of it to the pilot, when a human decision is required. The actual flying of it is the easiest bit. You don’t even think about it any more.”

For those of us with wild fighter pilot daydreams fuelled by Top Gun clichés, these advances could be rather disheartening. Just as our smartphones are seldom used for actual voice calls, the F-35 will rarely find itself in a Bruckheimer-esque dogfight.

Not your traditional fighter jet

This fifth-generation fighter jet is designed to be so much more multi-faceted than all that’s gone before it, and less likely to get itself into a confrontation in the first place.

It’s more about acquiring targets than attacking them, using its super-stealthy coating to sneak undetected into enemy territory before painting a vastly detailed picture of the battlefield for a team of people who’ll fire its weapons remotely. Or a gaggle of nimble fourth-gen fighters behind it that’ll swoop in and do the dirty work.

“The human still decides whether to fire a missile or drop a bomb,” Beck assures us. “There is a morality around warfare and some ethical decisions. At the moment no machine will ever make those. That’s why we’re still in the cockpit.

“That is fundamental to the way the RAF and Royal Navy do business. But we’ve got there by getting smarter and smarter. I’m in a great position now where my uncertainty of what’s going on is negligible. With certainty, I know ‘that’s the enemy, I know he’s doing a bad thing and I’ve got to make the decision to drop the bomb’.

“People think the move into fifth-generation jets is about stealth. It isn’t. It’s about information. Whoever has the most – which is of decision quality – will win the fight,” Beck says.

Read more about war:

How the F-35 uses data

With information the F-35’s biggest weapon, it’s something that needs sternly protecting. So Marham’s 150-strong cyber team is on the clock 24/7. All of the jet’s systems can be taken offline at any second, allowing it to function even if the cloud it usually connects to has been compromised.

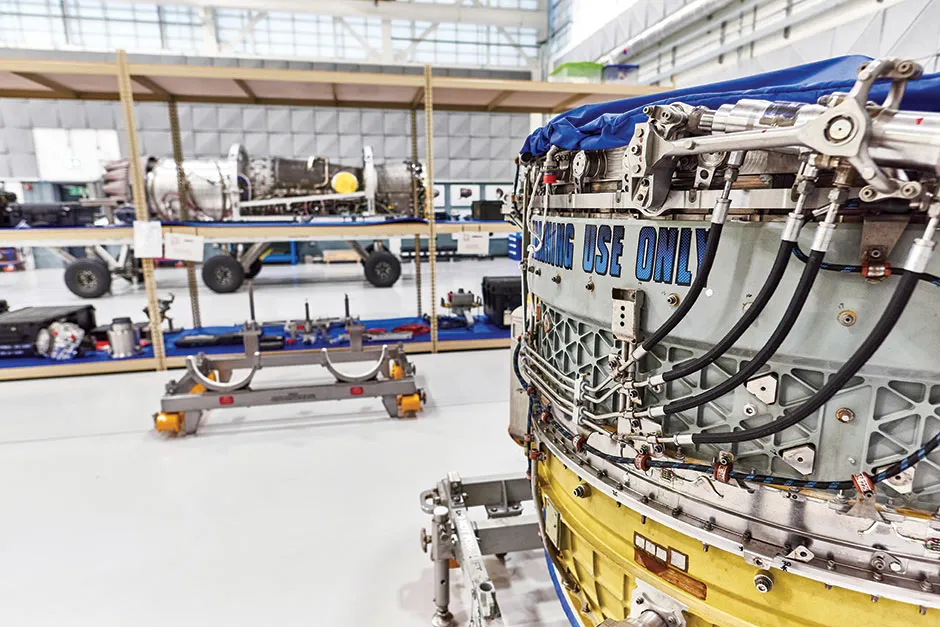

The Lightning II’s intelligence stretches to predicting its own needs, so after each flight its maintenance crew will plug it into the network, where the jet will advise what – if anything – failed during the flight or needs some attention in the near future.

I’m taken on a tour of Marham and spend an hour in the classroom. This is where the maintenance crew learn their trade, on something unemotionally named the Air System Maintenance Training (ASMT) system.

In short, it’s a virtual fighter jet that you move an avatar around, with a bank of tools to drag in to help you learn every possible servicing or repair job before you’re let loose on a real-life jet. It operates a lot like virtual reality, but without the discombobulating headset.

As well as reserving any rookie errors for a mock environment, the virtual system also saves the hours it can take to laboriously remove panels to get under a real F-35’s skin. The fighter jet is so hard to get inside because the panels are often masked over so that no gaps or rivets break its sleekness.

The craft needs to be as smooth as possible so that it can evade radar and maintain its exceptionally high stealth levels. Not only is the removal of panels tricky, the resealing process once you’ve popped them back on is drawn out, too.

Next door to the ASMT room is the laboratory where students learn how to fix this ‘low observation’ surface of the craft. While this lab also has computerised processes, with its focus on fine craftsmanship it feels like more of a blast from the past.

There’s even a paper sheet on the wall to help both trainers and trainees convert from the F-35’s imperial measurements – betraying the aircraft’s US manufacturer – into the metric they most likely know.

One big question looms large, though. Is the F-35 just too clinically adept to make its pilot a hero?

“Not when you’re doing ‘doggers’, as we call them,” Beck says. “We fly a thing called angle of attack [AOA]. While a Tornado could go 19AOA, we’re going to 50AOA. We just keep going up, and the last person to stop going up will win that fight. And that’s absolutely exhilarating.

"If I tried that in a Tornado I’d be in a parachute. There is a bit of romance about flying older planes, but we’re a professional force and it’s more about what the jet can do. The dogfight takes place on the information spectrum now.

“All the controls only move for human comfort, the jet doesn’t need them to operate. They’re about making it easier for pilots to comprehend. It’s making me feel good by moving left. You ask the jet ‘can I do something’ and the jet will do it if it’s safe to do so. It won’t let you fly into the ground or into another jet, it’ll just say ‘no!’ It’s just breathtaking, it really is.”

So there’s little chance you’ll end up in the disastrous flat spin that leads to Goose’s galling demise in the original Top Gun, then.

“I like talking about the jet, it’s my second favourite subject,” concludes Beck, with a wry grin. “What’s the first? I’m a pilot…”

Maybe there’s a little bit of Maverick in him after all.

- This article first appeared in issue 352 ofBBC Science Focus–find out how to subscribe here