Most people dislike jellyfish. They fear their venomous sting, hate their jelly-like consistency and see little merit in their continued existence. Like wasps, many people believe we would be better off without them.

But is this a balanced view of an animal that has existed for far longer on the planet than man, and which belongs to an ancient lineage that weathered the extinction of animals as diverse as dinosaurs and trilobites?

Jellyfish have a reputation for being dangerous, despite the fact the majority of species inflict a weak sting, barely noticed by swimmers. Admittedly, the variety known as ‘box jellyfish’ are potentially lethal, but they exist far from our shores and the majority of those species that regularly invade our shoreline, like the moon jellyfish and the compass jellyfish, leave little impression other than a mild skin irritation.

True, the well-known Lion's mane jellyfish, can inflict a painful sting, though it would be most unusual for this to prove fatal as it was in the story of the same name by Arthur Conan Doyle. The Portuguese Man-of-war, in fact a colonial hydroid rather than a true jellyfish, can certainly inflict harm, but it is a relatively uncommon invader of our shores.

Read more about jellyfish:

When we examine our attitude to different animals, this is inevitably influenced by what they’re able to offer us. So, bees pollinate our flowers and give us honey. They are seen as ‘good’, despite the fact their sting is painful and can even result in anaphylactic shock.

Tigers are a protected species and effort goes into conserving them despite the fact they are aggressive predators and, on occasions, pose a threat to us.

On the other hand, slugs and snails are seen as unwanted creatures, the gardeners’ chief enemy, and appear to offer us little, other than perhaps a food, if so inclined. We forget that all animals, large or small, have mixed qualities, some that are desirable and others that are a nuisance or even harmful to us. Jellyfish are no exception.

Let me list some positive attributes of jellyfish.

First, they are a source of food. Leatherback turtles, penguins and several varieties of fish eat jellyfish. Some jellyfish devour other jellyfish. They are also eaten by humans, notably in South East Asia, where they are regarded as a delicacy.

In China, Japan and Vietnam they are farmed, stripped of their sting and sold on to restaurants. Valued particularly for their texture, they are consumed in large numbers, and have been for centuries. Now, even in Western Europe, they are used in the manufacture of foods as diverse as crisps and ice cream.

But it is the contribution they make to scientific endeavour that really tips the balance in favour of jellyfish.

The discovery of anaphylaxis owes its origin to experiments with Physalia, the Portuguese Man-of war. It resulted in a Nobel Prize for Charles Richet who led the research. Another Nobel Prize was shared between Osamu Shimomura, Martin Chalfie and Roger Tsien who extracted from the crystal jellyfish a fluorescent substance called green fluorescent protein which has proved revolutionary in biomedical research.

It was known that this jellyfish emitted pinpricks of green light from the margin of its bell. The light, initially blue, came from a molecule known as aequorin and was absorbed by a green fluorescent protein which, in turn, re-emitted this energy as green light. Once the gene responsible was sequenced, it proved possible to introduce green fluorescent protein into animal cells.

As a ‘tagging tool’ it proved possible, because of its light-emitting properties, to follow viruses, bacteria and embryonic cells as they divided and spread through animal tissues. This protein also carries with it the potential for studying tumour spread and for better understanding the way nervous systems develop. The pictorial result alone, from fluorescent mice to green zebrafish nerve cells, is spectacular as the picture shows.

Another unusual property of jellyfish is their ability to regenerate, to the extent that, in at least one species, Turritopsis dohrnii, the animal is able to ‘age in reverse’. As a result of being damaged, the so-called ‘immortal jellyfish’ curls into a ball, absorbs its own tentacles and puts out ‘stolons’ which lengthen to produce polyps. These in turn become ‘new’ jellyfish.

Could this small creature contain the secret of immortality? Or will it, or its cousins, provide us with a better understanding of how we could repair our own diseased tissues?

It may surprise people to know that jellyfish have also made a contribution to our understanding of the effects of microgravity on the human body. Several hundred immature moon jellyfish were sent into space to see if weightlessness affected their gravity sensors. These contain calcium, similar to that found in the human inner ear.

The calcium crystals in the orbiting jellyfish failed to develop normally. This is likewise a potential problem for astronauts who spend months at a time weightless onboard a space station. As an experimental animal, jellyfish could provide the solution.

Of course, there will always be exaggerated claims for the benefits of jellyfish extracts, from improving memory to ameliorating arthritis. Sadly, most of these claims do not stand up to scrutiny. One that looks promising however is the use of collagen extracts from jellyfish.

Dressings made from collagen extracted from the barrel jellyfish appear to speed up the rate of healing in ulcers, a condition that causes a lot of debility in humans.

The venom jellyfish produce, while harmful, may also paradoxically be a source of pain-relieving drugs similar to the cono-peptides derived from the venom of certain species of sea snail. This is research in progress.

Finally, we know that jellyfish thrive when conditions in the oceans deteriorate and when fish stocks decline. Indeed, they often flourish in the pollution that humans create. Jellyfish blooms are regarded by some as the most visible part of a distressed ocean ecosystem.

Read more about sea life:

While they act as pointers to the need to address climate change, they have also been shown to act as a sink for greenhouse gases through their ability to sequester carbon as their carcasses accumulate on the sea floor.

I hope I may have already convinced you that all is not bad in the world of jellyfish. I hesitate to point out that they have also been an inspiration to artists, sculptors, designers and architects... but that is a topic in itself!

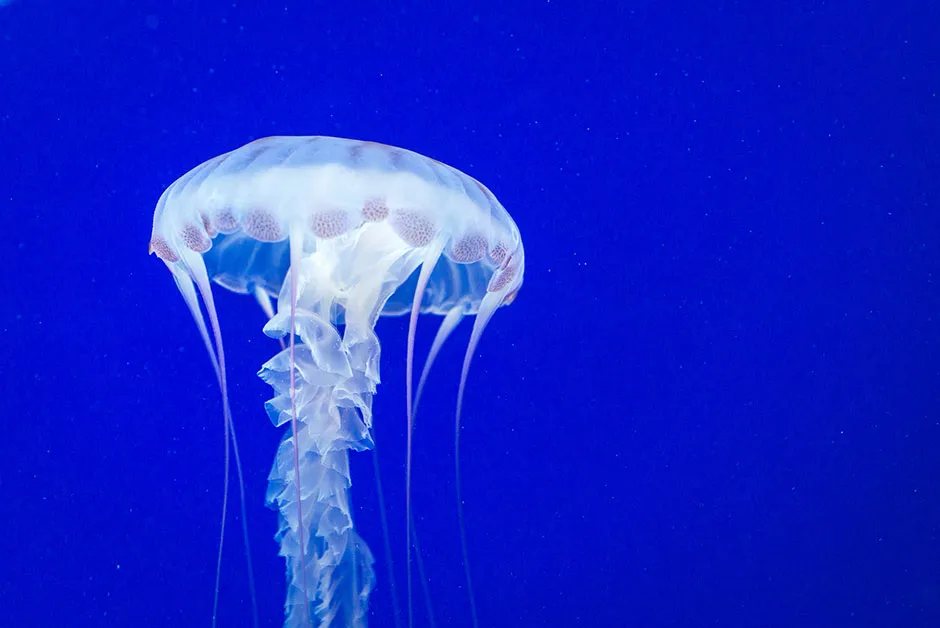

When next you visit one of the many aquaria that house jellyfish, spend a moment admiring their ethereal beauty, the charm of their pulsating movement and the variety of colour, shape and design they exhibit.

Ancient creatures without heads or complex nervous systems, they can nevertheless inspire wonder and contribute to our understanding of the planet and indeed ourselves.

Jellyfish by Peter Williams is out now (£12.95, Reaktion Books).

- Buy now from Amazon UK, Waterstones or WHSmith