Since the Middle Ages, humans have had a close relationship with honeybees as we’ve captured and reared them for their valuable and delicious honey.

Over time, however, captive honeybees started to outcompete wild honeybees, which were also losing habitat as their native forests were cut down. Then in the late 1940s, beekeepers in Africa started to see outbreaks of a virulent parasite – the Varroa mite – which quickly spread to hives in Europe and the Americas.

Now virtually every commercial colony in the world is infected with the Varroa mite, requiring treatment to prevent complete colony collapse. Because of the widespread distribution of the Varroa mite, people assumed that wild honeybee colonies must have also come under attack and been wiped out from their forest habitat in Europe.

So when Benjamin Rutschmann and Patrick Kohl – both PhD researchers at the University of Würzburg, Germany – headed out into the forest in search of wild honeybees, they didn’t know if they would actually find anything.

Read more about bees:

- Your garden is a lifeline for struggling urban bees

- Hotter temperatures could lead to a 'mass extinction' of bumblebees

They set up artificial feeders to attract honeybees in Hainich forest, northwest Germany, and then tracked the foraging bees back to their nest. Against all expectations, they found some wild colonies were still present in this ancient beech forest.

Suddenly, a fun weekend project between friends turned into a concerted scientific effort to map and monitor the bees that so many people thought had long since vanished.

Rutschmann and Kohl found the wild bees were often nesting in abandoned tree cavities created by black woodpeckers (Dryocopus martius), which are one of the few locations in these forests with enough space for the bees to house their food stores for the long winter months. Scientists studying black woodpeckers were able to provide precise coordinates of around 500 abandoned tree cavities in Hainich forest as well as the Swabian Alb Biosphere Reserve in southwest Germany.

“Every year we check all of these trees,” says Rutschmann. “We can find a couple of honeybee colonies a day, because [in the summer] about 10 per cent of all these woodpecker cavities are occupied by honeybees.”

Extrapolating from their data, they estimate that Germany’s forests may be home to several thousand wild honeybee colonies. However, these bees are not the stalwart survivors of an ancient dynasty of wild bees – they are more likely to be descendants of escaped swarms from commercial hives that have re-established in the woodland.

Rutschmann doubts they are forming long-term self-sustaining wild populations. “It looks very tough for these bees,” he says.

Where can you find wild honeybees?

Studying wild honeybee colonies in detail is no simple task. The cavities can be anywhere from 8 to 80 metres off the ground, meaning that researchers have to winch themselves into the tree canopy to get a glimpse.

To get a better view, photographer Ingo Arndt created a semi-natural nest by attracting a nearby colony to a fallen beech tree that he had moved to his back garden.

During the six-month project, he took more than 60,000 photographs, capturing behaviours that had only previously been observed within the constraints of commercial honeybee frames. For example, during the early stages of building the honeycomb, workers can be seen linking legs to form a long chain.

“These are often referred to as ‘festooning bees’. Lots of ideas have been advanced about why they do this, including acting as scaffolding for the developing comb and as a way of measuring space, but at the moment this is still something of a mystery,” explains Adam Hart, entomologist and professor of science communication at the University of Gloucestershire.

The chains are usually a single-bee wide, but Arndt’s semi-natural hive has revealed far more complex chain-forming behaviours.

“When the bees erect their combs freely in the three-dimensional space of a tree hollow, a sort of ‘bag’ of living bees, interlocked with one another, forms on the ceiling of the hollow,” explains Dr Jürgen Tautz, retired professor in honeybee biology at the University of Würzburg. “The net appears extremely flexible, its ‘meshes’ pulled tightly together at times and spread wide apart at others.”

This net of bees remains in place after the honeybees have constructed their comb, and Tautz speculates that it may protect against intruders and help control the climate inside the tree hollow.

What's it like to live in a beehive?

Zooming in even closer, Dr Bernd Grünewald, head of the Bee Research Institute at Goethe University in Frankfurt, has placed video cameras inside the honeycomb itself. By slicing a cross-section through the comb and covering the exposed cells with glass, the researchers were able to observe broods developing inside cells for weeks on end.

This technique has revealed unique insights into life inside the colony, from workers remodelling brood cells with recycled wax, nurse bees feeding larvae by mouth, and dedicated ‘heater bees’ using their own bodies to keep conditions inside the cells just right.

The heater bees’ job is to keep the brood cells at a constant 35°C. By climbing head-first into an unoccupied cell and radiating heat, they can warm up to 70 neighbouring brood cells.

“By activating their thoracic flight muscles – the most powerful they possess – bees can generate body temperatures up to 44°C,” says Tautz.

Read more about honey:

- Natural remedies: Can honey really help cure a cold?

- Post-surgical Manuka honey 'sandwiches' help fight superbug infections

Bees use this skill for all sorts of tasks, from warming up the hive to thickening honey. They even use it to defend the nest against attackers, such as hornets. Honeybees have a slightly higher maximum body temperature than hornets and they use this to their advantage by forming a defensive ball around any attackers, essentially cooking them to death.

“The bees vibrate their wing muscles, raising the temperature of the ball until the point where the heat kills the hornet. It’s brutal, but effective,” says Hart. “The crucial thing for the bees is to stop the hornet from getting back to her nest and leading more hornets to the bees.”

A hornet attack can decimate a honeybee colony in a matter of hours. As well as attacks from hornets and outbreaks of parasitic mites, honeybee colonies are dealing with the added stress of insecticide exposure from agriculture. Newly developed chemicals are tested for lethal effects on bees, but the effects of sub-lethal doses can only be detected with careful behavioural experiments.

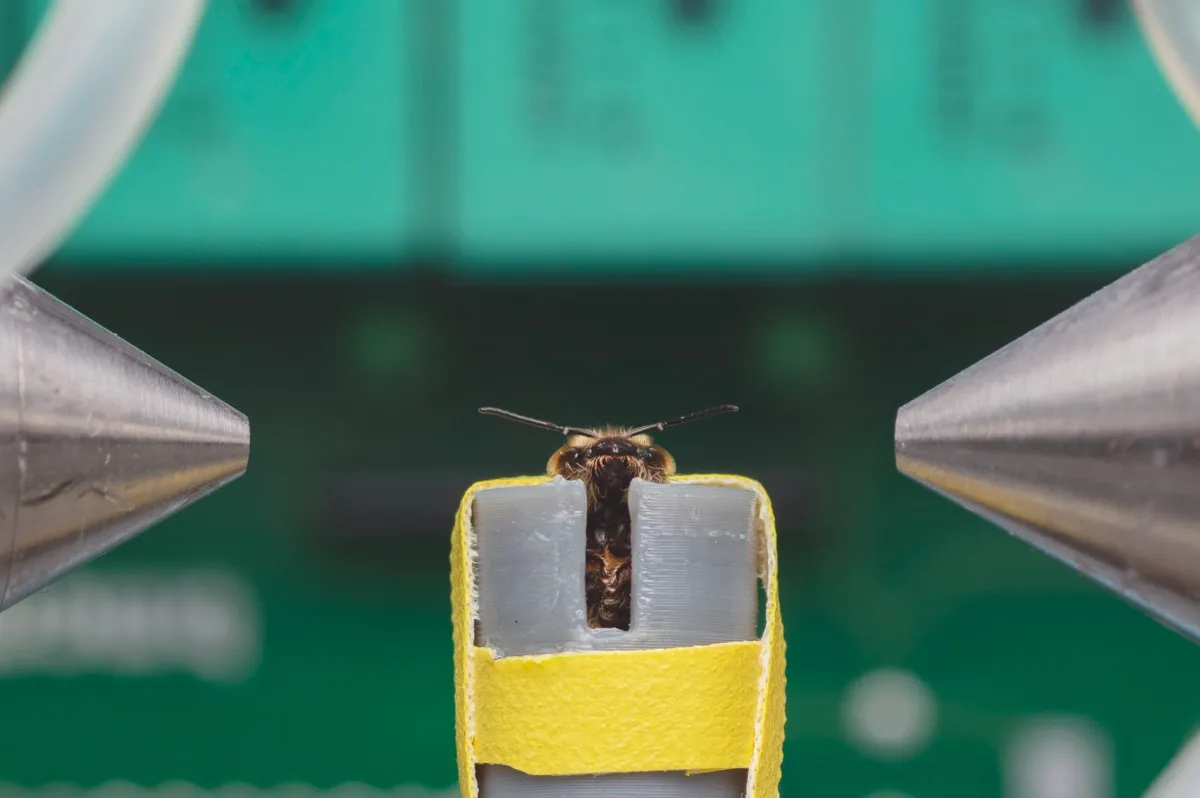

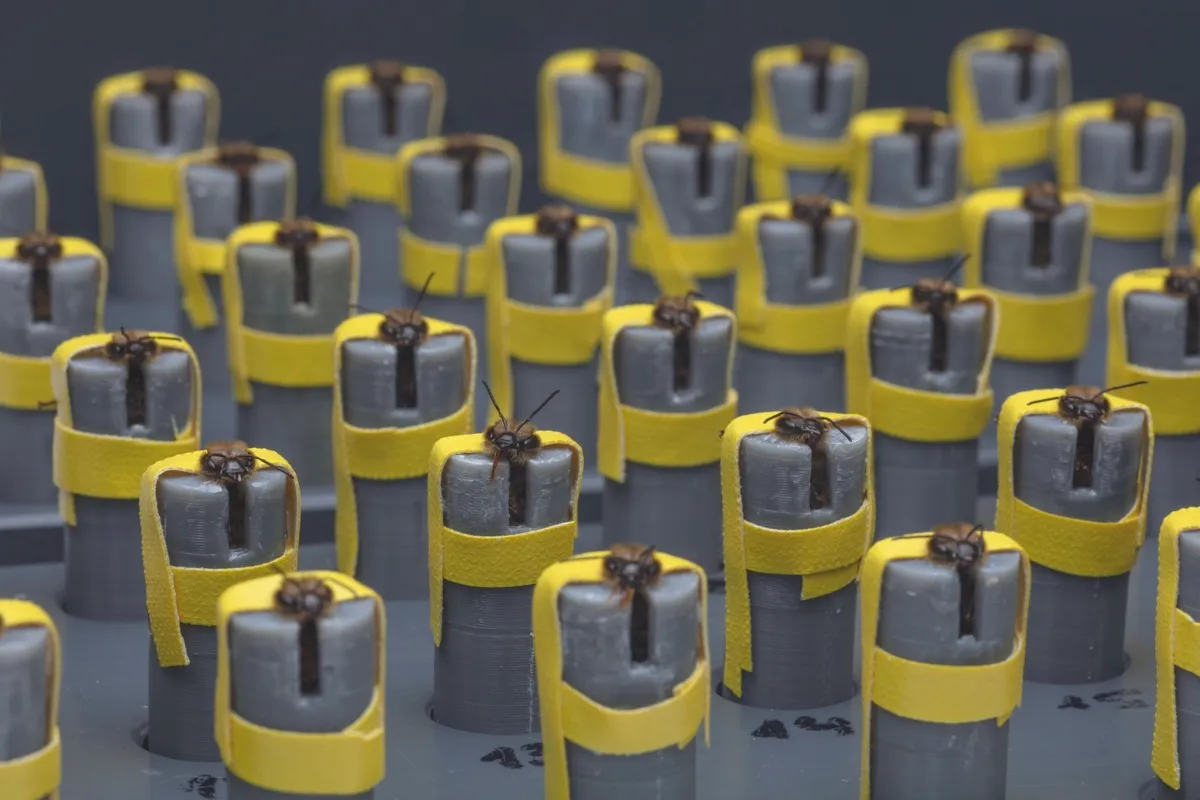

These experimental setups allow researchers to measure how individual bees respond to insecticide exposure by gently blowing low concentrations of the chemical over the bees.

How scientists study our striped friends

But captive laboratory hives are not just used to test the effects of pesticides. For decades, bees have been studied to help us further our understanding of their learning and memory, yielding data that may aid honeybee conservation. To study the bees’ learning abilities, researchers commonly use harmless restraints to hold them in place while they are exposed to, for example, a particular food or smell.

The bees are first chilled down to 4°C (about the temperature of your fridge), which causes them to fall asleep, but doesn’t harm them. While the bees are sleeping, researchers can strap them into tiny harnesses. Once in this setup, bees can be taught to extend their tongue-like proboscis in response to a particular stimulus, just like how the dogs in Pavlov’s well-known experiments learnt to salivate in response to the sound of a bell.

By providing the bees with a sugary treat alongside a particular smell, the researchers teach the bees to associate the smell with the food, and after many rounds, the bees will stick out their proboscis in response to the smell alone.

“It does look a little extreme but I have carried out this procedure with honeybees and they are all released safe and well afterwards – indeed, it is essential they are unharmed, because if they weren’t we couldn’t study their memory or how they learn,” explains Hart.

These ‘proboscis extension reflex experiments’ have provided scientists with a wealth of information about the learning and memory capabilities of bees, and the same techniques have even been used to train bees to detect illegal drugs and landmines!

With this arsenal of research methods, scientists are continuing to gain insights into bee behaviour, ecology and conservation, but many mysteries remain. Can wild honeybees survive in the forest long-term, and if not, why not? And what really is the purpose of those bizarre construction nets?

“More questions arose from the studies of the bees in the woods, than we got answers,” says Tautz.

Rutschmann says he plans to continue studying the feral bees in Germany to understand how they find food in the forest environment and what factors affect their long-term survival. Let’s hope they have a bright future ahead.

About our experts

Prof Adam Hart is an entomologist and the university’s Professor of Science Communication. He is also a broadcaster, appearing on BBC Radio 4 and the BBC World Service.

Prof Jürgen Tautz founded the honeybee biology research group, BEEgroup, at the University of Würzburg in 1994. His work has featured in the likes of Science and Nature journals.

Benjamin Rutschmann is a PhD student at the University of Würzburg, where he studies honeybee ecology. His work has been published in journals including the Journal of Experimental Biology.

- This article first appeared in issue 365 ofBBC Science Focus Magazine–find out how to subscribe here