- An aggressive type of brain tumour in infants and children, called high-grade glioma, could be successfully treated with targeted drugs instead of chemotherapy.

- The drug treatment, lorlatinib, significantly shrunk tumours in seven out of eight mice, while tumours in mice given chemotherapy kept growing, though at a slower rate.

- Clinical trials are planned "as soon as possible" says professor of paediatric brain tumour biology.

High-grade glioma brain cancer is almost always fatal in older children – with only 20 per cent surviving for more than five years.

But babies and very young children, diagnosed when they are younger than 12-months-old, tend to have a better outcome – with around two-thirds surviving five years or more.

The cancer in infants is biologically distinct from other childhood brain tumours, a new study suggests.

Scientists say their study, believed to be the largest of infant gliomas to date, found that these tumours are molecularly different from those in older children, helping explain why they tend to be less aggressive.

Read more on new cancer treatments:

- Flashing blue lights switch on cancer-fighting cells

- Statins could reduce ovarian cancer risk by 40 per cent

- Seek and destroy: beneficial bacteria programmed to fight cancer

According to researchers, the results could help pick out babies with tumours who could be spared chemotherapy.

Instead, the molecular weaknesses in the tumours could be treated with existing targeted drugs. Clinical trials to assess these are now open.

Scientists at The Institute of Cancer Research, London (ICR), carried out a large-scale study of 241 infants from around the world diagnosed with glioma brain tumours.

They worked with researchers at the Hopp Children’s Cancer Centre Heidelberg in Germany, the UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, and St Jude Children’s Research Hospital in the US.

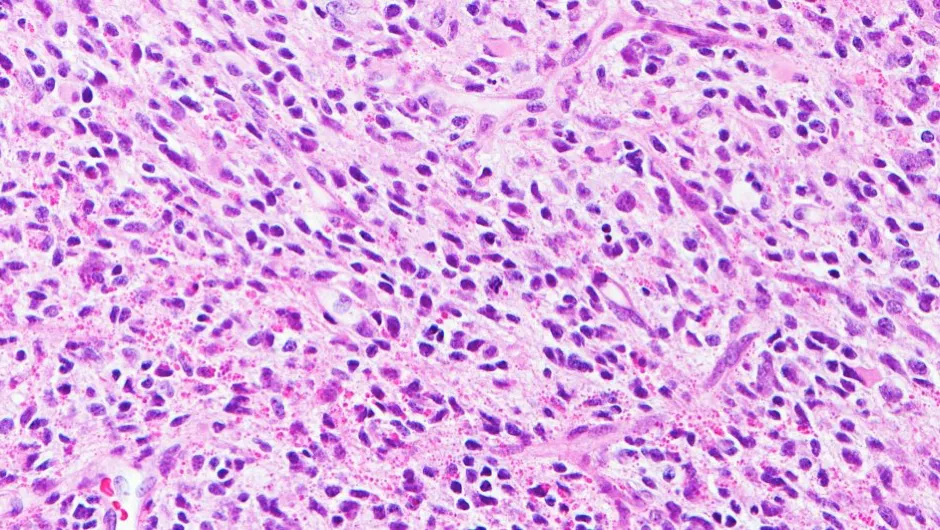

The researchers found that 130 of the 241 tumour samples had an entirely different genetic make-up from other forms of childhood brain tumours, despite looking highly similar under the microscope.

Researchers also looked at mice with brain tumours caused by the same weaknesses to compare the effect of a targeted drug, lorlatinib.

They found that lorlatinib significantly shrunk tumours in seven out of eight mice, while tumours in mice given chemotherapy kept growing, though at a slower rate.

A small number of children whose tumours were analysed in the study were successfully treated with the targeting drugs.

Chris Jones, professor of paediatric brain tumour biology at the ICR said: “Our study offers the biological evidence to pick out those infants who are likely to have a better outcome from their disease, so these very small children and their families can be spared the harmful effects of chemotherapy.

“We showed that brain tumours in infants have particular genetic weaknesses that could be targeted with existing drugs – and clinical trials are planned to test the benefit of these precision medicines as a first-line treatment as soon as possible.”

The study, published in Cancer Discovery, was funded by charities including the CRIS Cancer Foundation, The Brain Tumour Charity, Children with Cancer UK, Great Ormond Street Hospital Children’s Charity, and Cancer Research UK.

The results are also set to change the World Health Organisation’s diagnostic guidelines, with brain tumours in infants to be classed separately from other childhood brain tumours, say the ICR.

Reader Q&A: How does radiation kill cancer if it causes cancer?

Asked by: Odysseus Ray Lopez, US

It’s rather like the way guns can be used to commit crime, or stop it. Radiation causes cancer because its high-energy photons can cause breaks in the DNA strands in your cells. Cells can repair this damage up to a point, but sometimes the repair isn’t perfect and leaves some genes defective. If the break affects one of the many tumour-suppressing genes in your DNA, that cell can become cancerous. But cancer cells are also more vulnerable to radiation than ordinary cells. Part of what makes them cancer cells is their ability to divide rapidly and this normally means that some of the DNA ‘spellcheck’ mechanisms are turned off.

So when a cancer cell suffers a break in a DNA strand, it’s less likely to repair it correctly. Depending where the break occurs, it might either kill the cell outright, or make it reproduce more slowly. Radiation therapy uses a focused beam that is aimed at just the part of the body with the tumour, and the dose is carefully calculated to cause the minimum collateral damage to healthy cells. Even so, radiation therapy does very slightly increase your chances of developing a second cancer.

Read more: