Four bones belonging to a new species of dinosaur found on the Isle of Wight come from the same family as Tyrannosaurus rex, scientists say.

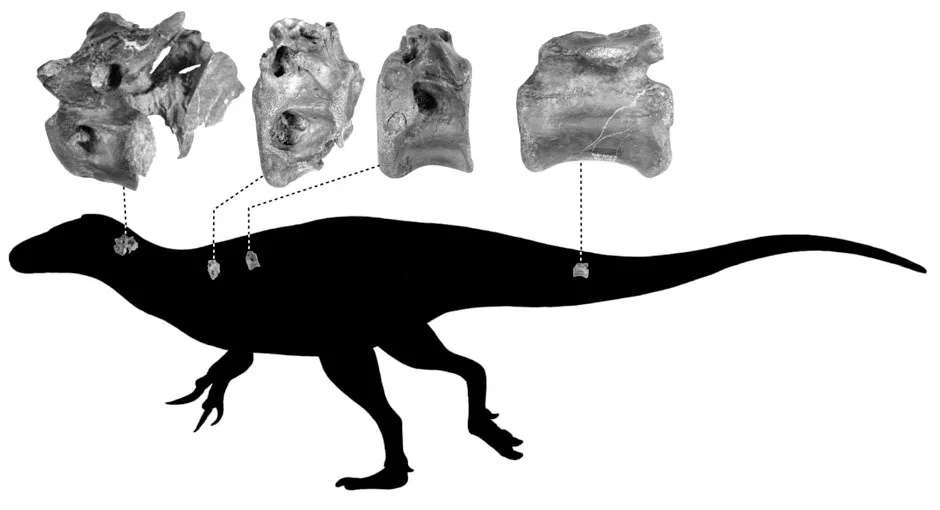

Palaeontologists from the University of Southampton say the creature lived in the Cretaceous period 115 million years ago and is estimated to have been up to four metres long.

The Isle of Wight dinosaur – which is a new species of theropod dinosaur, the group that includes Tyrannosaurus rex and modern-day birds – has been named Vectaerovenator inopinatus.

Read the latest dinosaur news:

- Meet the ‘tiny bug slayer’, a coffee-cup-sized relative of the dinosaurs

- Mystery solved: 240-million-year-old reptile with 'extraordinarily long neck' lived in the ocean

- Dromaeosaurid dinosaurs 'not only lived in the Arctic but thrived there'

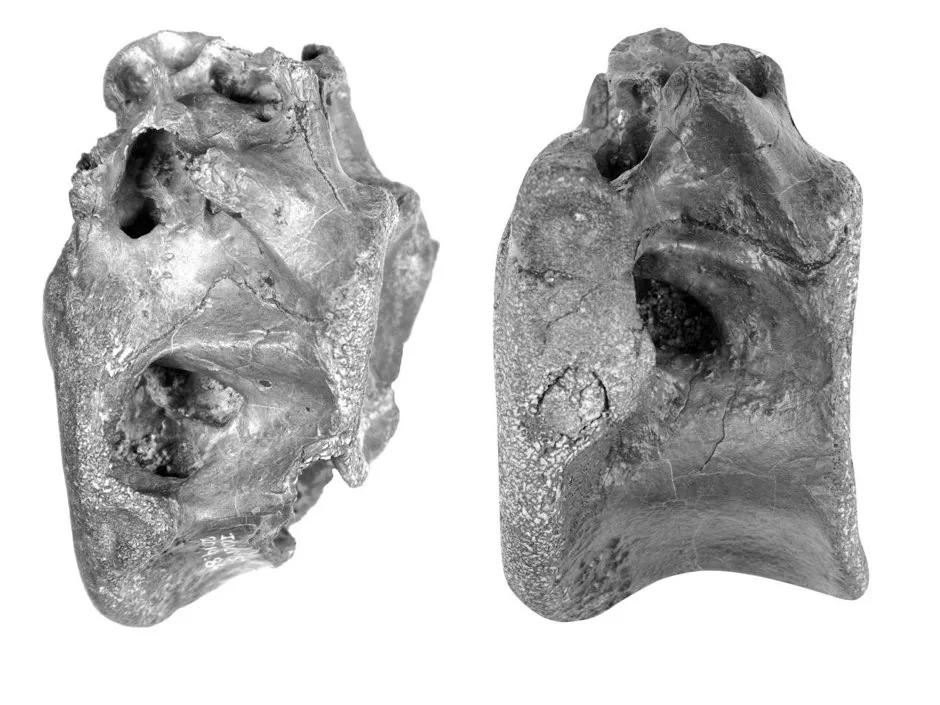

The name refers to the large air spaces in some of the bones, one of the traits that helped the scientists identify its theropod origins.

These air sacs, also seen in modern birds, were extensions of the lungs.

It is likely they helped fuel an efficient breathing system while also making the skeleton lighter.

The bones from this new dinosaur discovery are from the neck, back and tail, and were found on the foreshore at Shanklin last year.

The fossils were found over a period of weeks in 2019 in three separate discoveries – two by individuals and one by a family group, who all handed in their finds to the nearby Dinosaur Isle Museum at Sandown.

Scientific study has confirmed the fossils are very likely to be from the same individual dinosaur, with the exact location and timing of the finds adding to this belief.

Robin Ward, a regular fossil hunter from Stratford-upon-Avon, was with his family visiting the Isle of Wight when they made their discovery.

He said: “The joy of finding the bones we discovered was absolutely fantastic. I thought they were special and so took them along when we visited Dinosaur Isle Museum.

“They immediately knew these were something rare and asked if we could donate them to the museum to be fully researched.”

Read more about fossils:

- 200 million-year-old fossil shows dinosaur 'walked like a guineafowl'

- Mammal evolution: How ancient fossils are revealing the secrets of our earliest ancestors

- Dinosaur sex differences 'hard to spot' from fossils alone

James Lockyer, from Spalding, Lincolnshire was also visiting the island when he found another of the bones.

He said: “It looked different from marine reptile vertebrae I have come across in the past.

“I was searching a spot at Shanklin and had been told and read that I wouldn’t find much there.

“However, I always make sure I search the areas others do not, and on this occasion, it paid off.”

After studying the four vertebrae, palaeontologists from the University of Southampton confirmed that the bones are likely to belong to a genus of dinosaur previously unknown to science.

Their findings will be published in the journal Papers In Palaeontology.

Chris Barker, a PhD student at the university who led the study, said: “We were struck by just how hollow this animal was – it’s riddled with air spaces.

“Parts of its skeleton must have been rather delicate.

“The record of theropod dinosaurs from the ‘mid’ Cretaceous period in Europe isn’t that great, so it’s been really exciting to be able to increase our understanding of the diversity of dinosaur species from this time.

“You don’t usually find dinosaurs in the deposits at Shanklin as they were laid down in a marine habitat.

“You’re much more likely to find fossil oysters or driftwood, so this is a rare find indeed.”

Scientists say that it is likely the Vectaerovenator lived in an area just north of where its remains were found, with the carcass having washed out into the shallow sea nearby.

Reader Q&A: How do dinosaur footprints get fossilised?

Asked by: Rob French, Sheffield

In December 2018, over 80 dinosaur footprints were revealed at a site in East Sussex. They had survived for over 100 million years – and bear witness to the huge amount of luck involved in creating such fossils.

First, the creatures must step through sediment that is pliable enough to record their footprints, but not so pliable it gets washed away before being protected by fresh sediment. Each footprint then has three chances to become a fossil: as the original impression (the ‘true track’), as its fainter impression in the underlying layers (the ‘undertrack’), or by new sediment filling in the original impression (the ‘natural cast’) and hardening. Either way, as the layers of sediment build up, the pressure turns them to rock which – given yet more luck – will preserve the print intact for aeons.

Read more: