Ice sheets in Antarctica retreated at a much faster rate in the past compared to the most rapid pace observed today, according to scientists, which could help us better understand the consequences of climate change.

A team of researchers, which included experts from the universities of Cambridge and Loughborough, analysed the ancient wave-like ridges on the Antarctic seafloor thought to have formed during the last Ice Age around 12,000 years ago.

They found that Antarctic ice surrounding the coastline retreated as much as 40 to 50 metres per day during this period, equivalent to more than 10 kilometres per year.

In comparison, the researchers said, the fastest-retreating grounding lines – places where ice sheets no longer rest directly on the sea floor and begin to float – in Antarctica are currently about 1.6 kilometres per year.

Lead author Professor Julian Dowdeswell, director of the Scott Polar Research Institute at the University of Cambridge, said: “By examining the past footprint of the ice sheet and looking at sets of ridges on the seafloor, we were able to obtain new evidence on maximum past ice retreat rates, which are very much faster than those observed in even the most sensitive parts of Antarctica today.”

Read more about Antarctica:

- Penguins help researchers identify the most vulnerable areas of the Antarctic

- Antarctica rainforest once basked in 19°C summer temperatures

- Antarctica: the remarkable life that survives the coldest continent

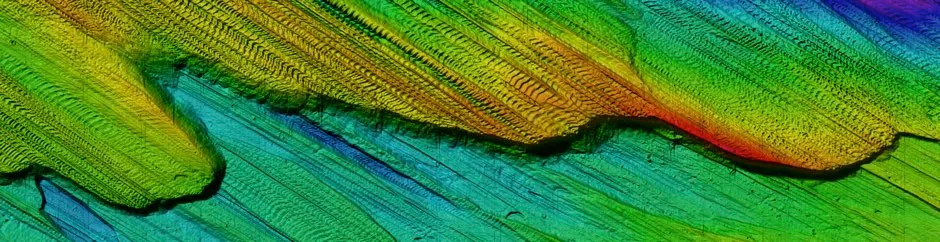

An autonomous underwater vehicle was used map the seafloor and measure the delicate ridges in the soft seafloor sediment on the Larsen continental shelf, off the east coast of the Antarctic Peninsula.

These wave-like structures, each about one metre high and spaced 20 to 25 metres apart, were thought to have been left behind by retreating ice nearly 12,000 years ago.

The scientists believe these small ridges were caused by the movement of the ice with the tides, “squeezing the sediment into well-preserved geological patterns”, resembling “the rungs of a ladder”.

Prof Dowdeswell said: “By examining landforms on the seafloor, we were able to make determinations about how the ice behaved in the past.

“We knew these features were there, but we’ve never been able to examine them in such great detail before.”

The scientists say their findings provide an indication of how quickly massive ice sheets can retreat, which if repeated, which would have implications for modern-day sea-level rise.

Prof Dowdeswell said: “We now know that the ice is capable of retreating at speeds far higher than what we see today.

“Should climate change continue to weaken the ice shelves in the coming decades, we could see similar rates of retreat, with profound implications for global sea level rise.”

The results are reported in the journal Science.

Reader Q&A: Will there be another Ice Age?

Asked by: Randall Barfield, USA

Oddly enough, an Ice Age has gripped the Earth for most of the last 2.6 million years, and we’re currently experiencing an unusually warm break from this so-called Quaternary glaciation, which temporarily lifted around 12,000 years ago. How long the ongoing ‘interglacial’ period will last depends partly on changes in the orbital size, shape and axial tilt of the Earth, and thus the intensity of sunlight, and also global warming – both natural and man-made.

A team at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, Germany, published research suggesting a complex link between sunlight and atmospheric CO2, leading to natural global warming. By itself, this will delay the next Ice Age by at least 50,000 years. Add in the effect of man-made global warming, and the delay is increased to 100,000 years.

Read more: