Back in 1848, Michael Faraday first gave his famous lecture series ‘The Chemical History Of A Candle’ at the Royal Institution Christmas Lectures. In doing so, he taught young boys in the audience about the physics and chemistry behind one of the most essential items in their homes.

The principle has stayed the same over the decades, with each year’s lecturer tackling contemporary topics in front of an audience of spellbound schoolkids. Now, 170 years on from discussing the science of candles, speakers have taken on topics like hacking your home, how to survive in space, and whether or not you could live forever.

While scientific knowledge has continued to improve, the presenters of the Christmas Lectures have consistently used over-the-top props and often nerve-racking experiments to get their young audience excited about the world of science. These 10 items mark some of the most significant moments in the history of the Christmas Lectures.

1

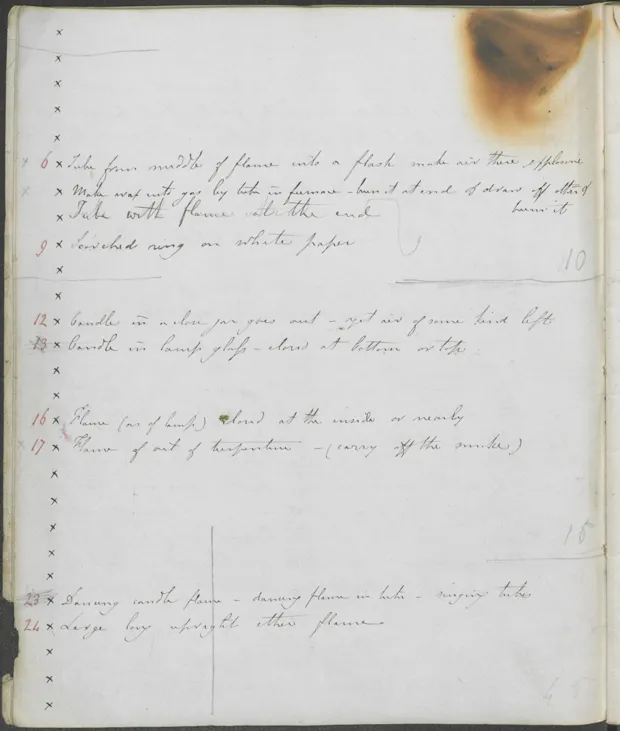

Michael Faraday’s burn marks

Michael Faraday launched the Christmas Lectures in 1825, and although he wasn’t the first presenter (John Millington hosted the debut lecture), he went on to give a record 19 lectures. His most well-known series, the Chemical History Of A Candle, was written up and is one of the best-selling science books of all time.

The Royal Institution still houses his meticulous notes from the lecture series, complete with a large burn mark across a few of the pages. Although no one knows exactly how it got there, Faraday’s lectures included experiments where he set fire to saucers filled with brandy, so perhaps it’s no surprise that some of his notes were scorched in the process!

2

Alexander Oliver Rankine’s homemade snow

Alexander Oliver Rankine, a British physicist, enthralled his audience by creating snow in the Royal Institution lecture theatre in 1932. He plunged a red-hot poker into a solid fuel called ‘meta fuel’, evaporating it, and it then re-condensing it into fluffy white particles in the air. In reality, this ‘snow’ had more in common with ash, but the effect worked.

Rankine also demonstrated to his audience that there was enough water vapour in the theatre for someone to ‘wash comfortably’; he used similar methods to develop a technology called FIDO, which was used to clear runways of fog during WWII.

3

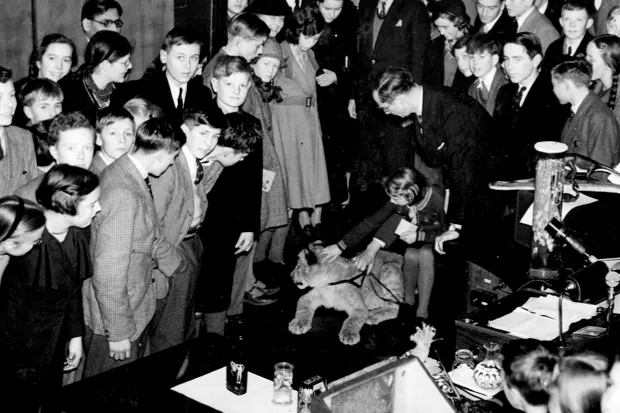

Max the lion cub

Julian Huxley, secretary of the London Zoological Society, gave his 1937 lecture on rare animals and the disappearance of wildlife. An active campaigner for endangered species, he showed his young audience a film of baby seals being clubbed in the Arctic, and brought in live animals from London Zoo, including snakes, crocodiles and a red kite.

But the audience’s favourite animal was Max, a lion cub. Huxley brought him in to show the audience that lion cubs have spots on their fur that fade as they reach adulthood.

4

Philip Morrison’s giant pencil

In 1968, inspired by Gulliver’s fictional travels, physicist Philip Morrison lectured on size and perception. He used a 12ft (3.6m) ruler and a giant pencil to measure a huge penny, to recreate how one of the inhabitants of Lilliput would’ve viewed Gulliver’s English pennies.

The enormous pencil and ruler recently got another airing when they were dug out of the archives by Mark Miodownik, a materials science who gave the Christmas Lectures in 2010.

5

Tammy the ring-tailed lemur

In 1973, David Attenborough brought out Tammy, an uncooperative ring-tailed lemur, to illustrate a point in his lecture on the language of animals. Ring-tailed lemurs have glands on the insides of their arms, from which they secrete a scent. When threatened, a ring-tailed lemur will rub their tail on the glands, then wave it around to create a curtain of smell. It’s a behaviour that help lemurs intimidate others, avoiding dangerous and tiring physical fights.

Unfortunately, Tammy wasn’t keen on showing his glands to the audience, but the kids were still charmed by the little lemur as he clung to Attenborough’s chest and gobbled up grapes.

What makes me ‘me’? – Aoife McLysaght

Evolutionary geneticist Aoife McLysaght joins Alice Roberts as a guest at this year's Royal Institution Christmas Lectures. Together, they're exploring where we come from, what makes us human, and what makes each of us unique. Listen to our interview with her in the latest episode of the Science Focus Podcast.

6

Richard Dawkins’ cannonball

In 1991, Richard Dawkins wanted to teach his audience to have faith in scientific predictions, so he held a heavy cannonball on a wire up to his face and let it go, so it swung across the room like a pendulum. Dawkins knew it wasn’t going to gain energy, so although his instincts told him to duck, he held his nerve, and the swinging cannonball stopped just millimetres from his face.

Dawkins was invited back in 2016 to repeat the experiment, but this time the cannonball had spikes. Dawkins again kept still as the cannonball stopped just shy of his chin.

7

Kevin Fong’s towel

In his 2015 lecture, Kevin Fong discussed how to survive in space, cutting back and forth between the Royal Institution and the International Space Station (ISS), where British astronaut Tim Peake had just taken up residence.

Fong discussed how astronauts stop their bones and muscles from wasting away when they’re living in zero gravity, and also explained how to cope with a medical emergency in space. Fong was able to send a practical present up to the ISS – this nifty hand towel, to remind Peake of the golden rule when facing a medical emergency: don’t panic.

8

H5W: the keyboard-playing robot

Danielle George created an entire robot orchestra for her 2014 Christmas Lecture, and one of its most impressive members was H5W, a piano-playing robot created by Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona. The robot was able to play specific notes when asked, and tapped out the start of Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star. The robot claimed that the task was quite simple.

During the orchestra’s performance, H5W played the theremin, an instrument that consists of two metal antennas.

The antennas sense the position of a musician’s hands, and the musician then plays the theremin by moving their hands around. Playing a theremin involves constantly listening to the sounds you’re producing and adjusting on the fly. H5W mastered the task with ease, making it one of the stars of an orchestra that also included an old dot-matrix printer, a drone, and pipes made from shelving.

9

The world’s largest lemon battery

In his 2016 lecture, materials chemist Saiful Islam demonstrated that you can create voltage with just a lemon, a copper nail, a magnesium strip and a few wires. He then took 1,013 lemons, cut them all in half, connected them together, and created the world’s largest lemon battery. It was so large that it had to be filmed in the antechamber outside the lecture theatre.

With adjudicators looking on, Islam set a Guinness World Record for the highest voltage produced by a fruit battery, clocking in at 1275.4V.

10

Sophie Scott’s smell cannon

To illustrate how powerful scent messages can be as a means of communication, in 2017 neuroscientist Sophie Scott loaded up a cannon with some pungent smells and puffed huge, aromatic smoke rings at the crowd. Luckily for them, the first smelt a little like candy floss.

She then loaded the cannon with a synthesised version of the molecules in poo, and shot those smoke rings at some unsuspecting audience members, who took it quite well. Her point was that smells contain important information, and that while a candy floss aroma tells us something might be edible, a poo smell lets us know that an object might be contaminated, and it’d be best not to consume it.

Scott also gave us a glimpse into direct, silent communication via brain waves, suggesting that’s how we could exchange ideas in the future.

This is an extract from issue 330 of BBC Focus magazine.

Subscribe and get the full article delivered to your door, or download the BBC Focus app to read it on your smartphone or tablet. Find out more

The search for the missing Christmas Lectures

Although you can watch most of the previous Christmas Lectures on the Royal Institution website, there are still 31 episodes that have been lost to the sands of time (read: officially 'believed wiped'). That is, unless you have a copy of them buried in the attic.

The Royal Institution is currently on the hunt for five complete sets of lectures from between 1966 and 1971, as well asa single episode of Sir David Attenborough’s much loved 1973 series on ‘The language of animals’. Do you think they could be lurking somewhere in your home or stored somewhere safe?

You can find out more at www.rigb.org/christmas-lectures/missing-lectures,but anyone with clues as to their whereabouts should Charlotte New, Curator of Collections at the Royal Institution on 020 76702923 or email her at cnew@ri.ac.uk. You can also join in the conversation using#missingxmaslectures on social media.

The missing episodes are:

1966 – Engineer in wonderland – Eric Laithwaite

1967 – The intelligent eye – Richard Gregory

1969 – Time machines – George Porter

1970 – Monkeys without tails: a giraffe’s eye view of man – John Napier

1971 – Sounds of music: The science of tones and tunes – Charles Taylor

1973 – The language of animals (1 episode) – Sir David Attenborough

Happy hunting!

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard