The Orionid meteor shower peaks over the UK between midnight and dawn tonight. If you're going to try to see it, first have a look at our guide to stargazing without a telescope to make the most of what you can see, extracted from Abigail Beall'sThe Art of Urban Astronomy.

Stargazing does not have to be complicated.

It really can be as simple as looking up and noting the things you can see. If you look regularly enough you will start to notice patterns in the stars, planets moving and the moon changing its shape. That’s stargazing.

But once you start to try and search for new stars, constellations and objects in the night sky, there are a few tricks and techniques that will become very valuable to you.

Stargazing with your eyes

Everyone knows that feeling in the middle of the night when you wake up and realise you need a wee. You lie there for a few minutes trying to decide between going back to sleep and putting it off until the morning (normally my preferred option) or just getting up and going.

Eventually, it becomes so desperate that you must leave the warmth of your lovely bed and go to the cold loo.You make it out of the bedroom just fine. You get to the bathroom and decide you need to see what you are doing.

If you have to put the light on in the hallway or in the bathroom, though, when you come back to the dark room, suddenly you can’t see anything at all. This is what it’s like trying to look at the stars when your eyes are not adjusted to the darkness.

The point of this story is, your eyes need time to adjust to the darkness so they can see the light from the stars. The first step in your eye adjusting to changes in light concerns the pupil.

If you get someone to close their eyes for a few seconds, then open them again, you should notice their pupils becoming much smaller in reaction to the increased brightness. The pupil is a hole in your eye that lets light in. When it’s darker, the pupils need to be bigger in order to let more of the light in.

This process happens in a matter of seconds, but it’s not the only step in your eyes adjusting to the darkness, a process called dark adaption. In fact, the whole process takes forty minutes.

Read more about watching meteor showers fromBBC Sky at Night:

Behind your iris inside your eye is your lens, which, if it works correctly, bends the light so it focuses exactly on your retina, the surface at the back of the eye connected to the optic nerve.

For many people, like me, the lens doesn’t work as it should. In my case, my lenses bend the light in my eye way too much, focusing the light in front of my retina, so I am short-sighted.

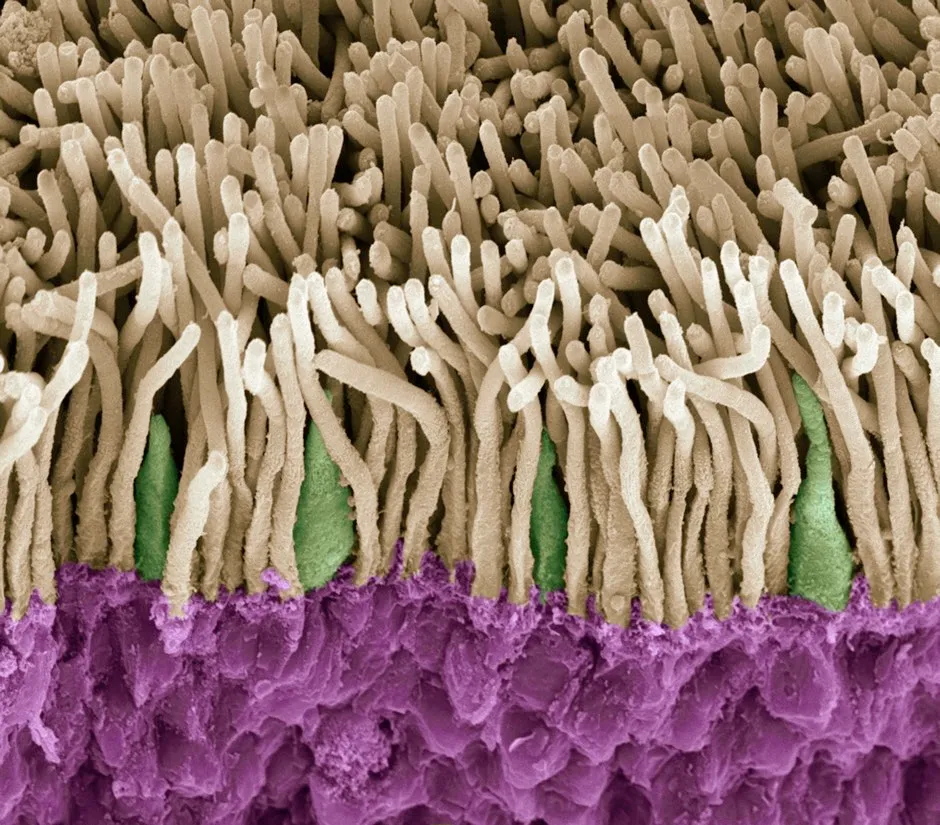

On the retina there are light-sensitive little detectors called rods and cones. Rods are much more sensitive than cones, and they kick in when the light is low. It is these little detectors that take a while to adjust to the low light.

In dimly lit situations, the rods start to produce a molecule called rhodopsin, which allows the retina to be stimulated when light hits it. This process can take an hour to happen fully but is ruined straight away if you look at a bright light.

If you are in your garden, on a balcony, roof or even just sticking your head out of your highest window, turn off all the lights in your house. If you are using a phone, install an app with a red-light filter and turn the brightness down as low as possible, so you can still look at the screen. Ideally, though, you want to put the phone away.

Then, be patient. Around ten to fifteen minutes later, you should start to see a lot more. Then, forty minutes later, your eyes will be fully adjusted.

Read more about astronomy:

- The Antikythera Mechanism: the ancient Greek computer that mapped the stars

- Cave paintings reveal ancient Europeans’ knowledge of the stars

There is another trick related to looking at faint objects. Looking straight at something makes the light hit a part of the retina called the macula. This is where most of the 6 million cones in your eye sit. But there are 120 million rods in your eye, and these sit around the macula.

If you can’t quite see a faint star, or can’t see it very well, look slightly away from the target you are trying to look for. You will see it appear in the corner of your eye, as if by magic. This is because it’s now being picked up by the rods around your macula, instead of the cones within it. This is called averted vision.

If you really need a torch to find your way around but don’t want to ruin your adapted eyes, use a red light. You can buy red lights online or use a red bicycle light if you have one.

The red part of the electromagnetic spectrum is what the rods in your eyes are least sensitive to, so it’s the best light to use if you do not want to ruin the dark adaption you spent an hour on. Having said that, try not to get a light that is too bright, as even red lights will ruin dark adaption if they are bright enough.

It really is best not to use any source of light at all.

The Art of Urban Astronomy by Abigail Beall is out now (£12.99, The Orion Publishing Group)