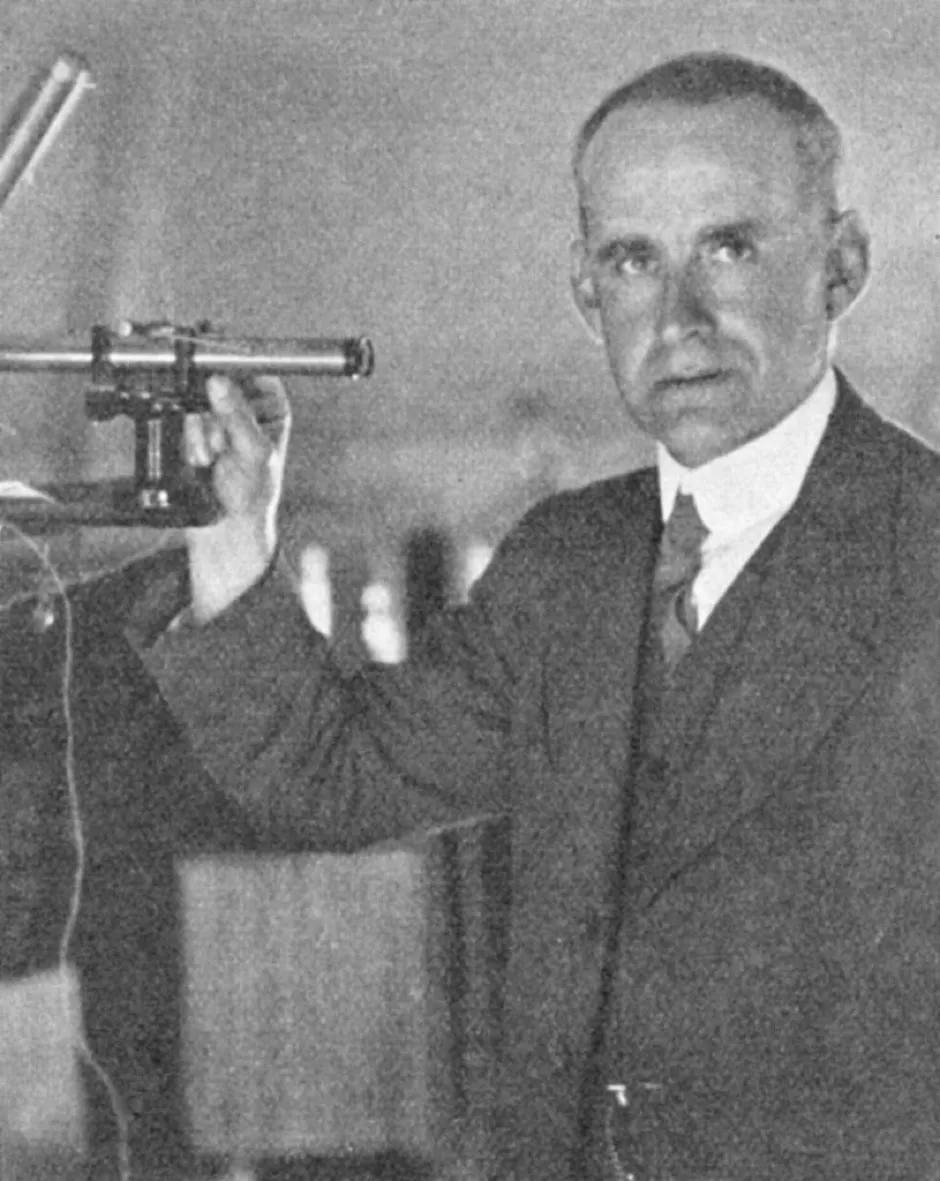

The theory of general relativity was Albert Einstein’s masterpiece. We like to imagine him, alone in his office in November 1915, writing down those equations and changing the Universe forever. But it wasn’t one moment – he had been struggling with theory for a decade – and he wasn’t alone. Einstein needed lots of allies to revolutionise science. Most important was one British astronomer: Arthur Stanley Eddington. His name is usually connected to Einstein because he carried out the expedition that provided the first evidence relativity was true (and made Einstein famous). His contributions to relativity, though, went far beyond that experiment.

When Einstein completed his theory in 1915 Berlin, almost no one knew about it. This was because, deep into the First World War, Germany was blockaded by hundreds of miles of trenches and the Royal Navy. It was nearly impossible for scientific papers to cross the battle lines. And even if they did, British and French scientists had resolved to never engage with “enemy” science again. The horrors of the war meant that German science had become abhorred – how could the scientists who created chemical weapons ever be trusted?

Read more about great scientists:

- James Clerk Maxwell: the most important physicist you probably haven't heard of

- Lise Meitner: the nuclear pioneer who escaped the Nazis

Einstein, a committed pacifist, hated German militarism as much as any of the Allies, though that made little difference. His few contacts outside Germany included friends in the neutral Netherlands, one of whom decided to try to spread relativity in England. By great fortune, that letter was read by Eddington. This was lucky not just because he could understand the complicated mathematics, but because as a Quaker, he was deeply committed to pacifism and internationalism in science.

Eddington decided to dedicate himself to promoting relativity and Einstein (both still largely unknown) as a way to simultaneously advance science and show the importance of it rising above the nationalism of the war. His first task was to learn relativity himself. At this time only a handful of people understood the theory, all of whom had been able to work personally with Einstein. Eddington, on the other side of the blockade, did not have that luxury. He struggled, and with the help of occasional letters from their mutual Dutch friend, mastered it by 1918. He then had to explain it to everyone else.

He gave popular lectures on relativity to excite the public, and wrote the first full treatment of the theory in English, The Report on the Relativity Theory of Gravitation. His efforts had much wider circulation than anything that Einstein had written. Most of the first people who learned about relativity probably did so through Eddington, not Einstein.

Convincing actively anti-German scientists and laypeople would take more than just education, though, and Eddington set his sights on a spectacular confirmation of relativity. Einstein had predicted that, as Eddington put it, light had weight. This could be detected only at a total solar eclipse with the most delicate of measurements.

Einstein had tried to have this test made for years, failing over and over. In wartime Berlin it was impossible. Eddington decided he could perform the test himself at the upcoming eclipse of 29 May 1919. He was friends with the Astronomer Royal Frank Watson Dyson, who secured funding and the support of the Royal Observatory Greenwich. They would send two teams to observe the eclipse, one to Brazil and one led by Eddington to Príncipe, a tiny island off the west coast of Africa.

Preparing the equipment and gathering team members was difficult because of the war, and it even seemed likely for a time that Eddington might be thrown in prison for his conscientious objection to conscription. In the end, the armistice came at just the right moment for the final preparations to be made and the expedition teams to embark on the U-boat ravaged Atlantic shipping routes.

Read more:

- First ever image of black hole revealed

- Dark energy is hiding in our Universe - here's how we'll find it

Before he left, Eddington made special efforts to prepare the press for maximum exposure for Einstein after he returned from the expedition with the results. He and Dyson arranged for a series of newspaper articles over the first half of 1919 explaining the significance of relativity, Einstein, and the eclipse, so as to whet the appetite of the reading public and the scientific community. Eddington, a master storyteller, framed the test as being one between Einstein and Newton – would this upstart German dethrone the greatest English thinker of all time?

The eclipse expeditions took months of travel, and had to persevere through bad weather, steamship strikes, and equipment malfunctions. After returning to England with a precious case of photographs, it still took months of measurement and calculation before Eddington and Dyson could announce the results: “there can be no doubt that they confirm Einstein’s prediction.” The response was tremendous – the President of the Royal Society declared it to be “one of the highest achievements in human thought.”

Eddington’s preparation with the media paid off handsomely. The Times headline blared “REVOLUTION IN SCIENCE.” Newspapers around the world followed suit with ever-more dramatic coverage. Einstein himself was hard to reach (Berlin was still in revolutionary chaos), and Eddington again was the gateway through which most people learned about relativity. His lectures in Cambridge had to turn away hundreds of people.

Having successfully catapulted Einstein to worldwide fame, Eddington’s next contributions to relativity were more prosaic but no less essential. He wrote some textbooks and taught some classes. For a new theory like relativity to become part of the scientific canon, young scientists needed to be taught how to use it.

Read more:

Eddington’s classes at Cambridge instructed a new generation of researchers (among them, future Nobel Prize winner Paul Dirac) in how to use relativity for their own investigations. His course notes became the foundation for two textbooks, Mathematical Theory of Relativity and Space, Time, and Gravitation, which allowed his formulation to spread throughout the English-speaking world. They remained the standards for teaching relativity for years to come.

He followed those texts with a series of best-selling popular science books, such as Nature of the Physical World and The Expanding Universe, that explained relativity for non-scientists. These became cultural touchstones not just for their clear and entertaining scientific exposition but for helping people understand the implications of the new physics for everyday human life, free will, and religious belief. His ability to champion science while also defending traditional values led him to be called “one of mankind’s most reassuring cosmic thinkers.” He would eventually be knighted for this work in 1930 and awarded the Order of Merit in 1938.

Eddington was not just a teacher and populariser of relativity, however – he was one of the first scientists to apply it to the problems of understanding the Universe as a whole. He a pioneer of the field we now call relativistic cosmology, which uses Einstein’s equations to determine the structure, history, and origin of the universe. Although he understood the possibility of an expanding Universe before most astronomers, he dismissed what we now call the “Big Bang” (a sudden, explosive beginning to the Universe) as “too unaesthetically abrupt.”

Like Einstein, Eddington spent the final years of his life trying to expand relativity into a unified field theory. Their goal was to reconcile relativity with quantum mechanics, a wholly incompatible but fantastically successful parallel branch of physics. And like Einstein, his attempt was an utter failure. Eddington’s particular approach tried to ground his new theory in an idiosyncratic philosophical position having to do with the human mind’s role in constructing reality. This was widely panned by his colleagues, and many scientists remember this failed project more than his contributions to the theory of relativity in general.

Without Eddington, relativity would have had a difficult time being established in the first place: his empirical confirmation of the theory, and his vigorous advocacy for it, were critical for its acceptance by physicists. But even beyond that, his teaching, writing, and technical application of relativity instituted it firmly as an essential part of scientific education and thought for the last century.

Einstein's War: How Relativity Conquered Nationalism and Shook the World (£16.99, Viking) by Matthew Stanley is out now.

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard