When Voyager I and II left our planet in the later Summer of 1977, they carried with them a pair of golden records.

The record was conceived as a message, a kind of multi-media CliffsNotes to life on Earth, full to the brim with music, sounds, greetings and even pictures, created on the off-chance that the probes are ever found by aliens.

It was compiled in the Spring of 1977 by a freelance team headed by Cornell professor and science communicator Carl Sagan, SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) legend Frank Drake, aided by writers Ann Druyan (creative director) and Timothy Ferris (producer); and artists Jon Lomberg (designer) and Linda Salzman Sagan (greetings compiler).

As a space-obsessed kid in the 1980s, I remember hearing about the Voyager Golden Record and thinking: "Yes, yes that’s all very interesting. Now show me more pictures of Uranus please."

Voyager II was in the thick of its Grand Tour of the outer planets at the time, and frankly a new moon or some previously unknown planetary rings were far more interesting than a record.

By the 1990s I was a full-bore indie kid, obsessed with music, and, more specifically, obsessed with forcing my taste on people via the medium of mixtapes.

Every now and then, the Golden Record would pop into my head, and I’d ask myself – did that really happen? Did NASA really make a mixtape for aliens? It seemed so out of character.

Read more about the Voyager spacecraft:

- The Voyager mission and our Pale Blue Dot: How the most famous picture in science came to be

- Voyager 2 sends back first signal from interstellar space

- Mission timeline: Voyager’s landmark moments

I first had a chance to write about the records in 2006. The 30th anniversary of the Voyager launch was approaching, and I interviewed Ann Druyan for Record Collector magazine.

It was a great pleasure to work on, but a single page in a magazine felt so unsatisfying.

These were, these are, genuinely, the strangest records ever made. They are the fastest records ever made: approximately 38,000mph. They are the furthest records ever made: Voyager 1 is currently over 22,500,000,000 kilometres from the Sun. They will be the oldest records: they’re likely to outlast our planet. And the more I discovered, the more fascinating they became. There were stories within stories, rabbit holes down rabbit holes. They were packed full of ingenuity, art, science and love.

So, I wrote a book about them.

Ultimately, my conclusions are that the reason the Golden Record was so successful, the reason it still inspires and delights us today, is that the LP’s creators stayed true to their audiences.

Everyone working on the project knew they were working for a potential alien audience, and a guaranteed human audience. Carl Sagan wrote in 1978 how the Golden Records were as much a time capsule for us, as a message in a bottle for them. And the fact that the record does function as both time capsule and interstellar message is what makes it so weird, in the best sense of that word.

First, the music.

Music is what we think of first when we see a record. This one has 90 minutes of the stuff, a generous helping of classical, a smattering of 20th-Century popular – including most famously Johnny B. Goode by Chuck Berry – and then a host of tracks from across the globe, including bursts of evocative field recordings of rite and ritual.

Producer Timothy Ferris will be first to admit that he was most concerned with the human audience. He wanted to make a ‘great record’ – an LP full of great music, that sounded great, but chosen from a wide cultural pool so it didn’t feel like a solely American project.

But even he talks eloquently about how they chose music not only because of emotional power or agreed quality of composition, but because of structures and patterns within – they hoped that this music could present interesting mathematic patterns for an alien to discern.

Tracks were chosen for unusual rhythms, for instruments employed, for types of vocal harmonies. They were grouped together to tell stories, so aliens might spot linking characteristics – a distinctive instrument heard in passing on one track, might be represented more fully in the next.

All kinds of factors shaped Earth’s mixtape, including of course, the personal tastes of those involved.

Mozart is one example. Mozart wasn’t really in the running as Carl Sagan felt this was too ‘lightweight’ for the space-going LP. Artist and friend Jon Lomberg, a huge Mozart fan, was absolutely horrified. So he made Carl a tape with three examples of Mozart, all quite short – as he knew anything too long would be less likely to make the cut.

In the end, Sagan green lit an aria from The Magic Flute, as in just three minutes of run-time it satisfied three categories – Mozart, opera, and, as it includes the highest note sung in traditional opera, the range of human vocal cords.

The music and the 12-minute Sounds of Earthsound essay came together in New York.

Read more about extraterrestrial life:

- Possible signs of alien life detected in Venus’s atmosphere

- SETI begins search for 'technosignatures' in the hunt for alien life

- Dr Helen Sharman: Aliens exist, there’s no two ways about it

Frank Drake and Jon Lomberg, meanwhile, were working out of the astronomy department at Cornell University, compiling a picture sequence of images drawn from coffee table books, image libraries and National Geographics. And they, without doubt, were totally focussed on the alien audience.

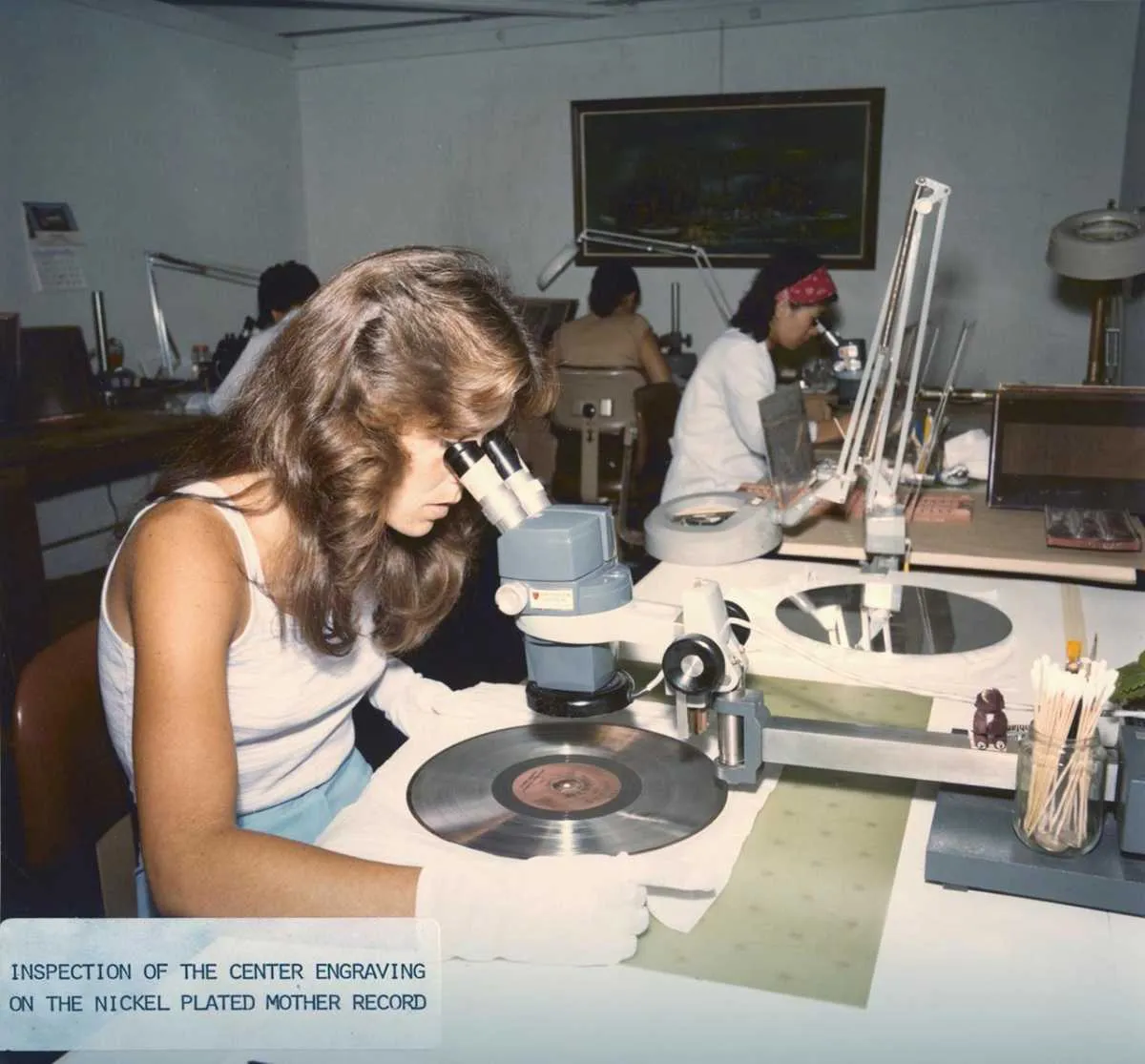

There are 120 images in total. And no, they weren’t printed in some booklet, record cover or metal liner notes sent with the records. These photographs were encoded into the grooves as sound.

Sorry, what?

Yup. The still photographs were converted into analogue video, and that video signal was converted into sound. This weird process took place in Boulder, Colorado.

Want to know what pictures sound like? Have a listen:

Now this brings us to the most mysterious part of the Voyager Golden Record – those cover hieroglyphs.

These markings were the brainchild of Frank Drake. In many ways they are design at its most pure – an attempt at communication without any common language or common cultural touchstones to rely on. And they’re really important as while NASA did send a stylus with the records, they didn’t send a turntable, so the aliens will have to build their own.

The cover assumes aliens can see, which of course they might not, or at least, their sight may function in completely different way to ours if their eyesight evolved under a different class of star.

But let’s assume, for now, that they can see.

The keys to the city are two little circles, shown here top left:

Those two circles represent the hyperfine transition of the hydrogen atom. To the alien that understands that the circles represent the hyperfine transition of the hydrogen atom, it hands them a unit of distance and of time. And using binary notation the cover hieroglyphs then ramp up that unit of time to tell ET how fast the record is supposed to revolve (16 rpm), and, once they have it revolving and have dropped the needle in the groove, how they should go about reconstructing the sound back into images.

Just to be clear, before I make my final observation, I love the Golden Record, and wouldn’t change an atom. However, I do worry that some of this may be lost in translation.

I worry about an alien, wearing headphones, seated in some distant lab, many millions of years in the future.

The Golden Record sits on a turntable, it’s revolving at the correct speed, and they’ve been listening to some music and voices when all of a sudden, the ancient alien artefact begins to emit several minutes of rasping white noise, punctuated by high-pitched beeps.

My worry is, they won't think: "Hmm, this sounds like a picture."

They might think: "Well this is a little too Avant Guard for me. Put Chuck Berry back on!"

Jonathan Scott’s book, The Vinyl Fronter: The Story of NASA's Interstellar Mixtape, is out now (£10.99, Bloomsbury Sigma).

- Buy now from Amazon UK, Foyles and Waterstones