When planets in our Solar System go into retrograde, you’ll often hear them being blamed as the source of a person’s woes, restlessness, burnout or, more optimistically, representing a time for reflection. In reality, however, there is very little scientific evidence that any of the planets going into retrograde will have a tangible effect on our lives.

Whether or not you believe this, planets going into retrograde is a common and regular occurrence, and on 4 September 2023, there will be six planets in retrograde at the same time… seven if you include Pluto.

But what exactly does retrograde mean? What planets are in retrograde right now? And what causes the apparent retrograde motion of the planets? Answers to these questions, and more, are below.

If you’re looking forward to making the most of clear nights this year, we’ve put together this full Moon UK calendar and astronomy for beginners guide to help you plan ahead. There are also regular meteor showers every year and we’ve rounded them all up in this handy meteor shower calendar.

What is retrograde?

The planets move from west to east across the night sky.

All the planets travel in the same direction around the Sun, and if you imagine a spot above the Earth’s north pole, they would be seen to travel anticlockwise. Anticlockwise motion is the ‘normal’ (more common) motion and is known as ‘prograde’.

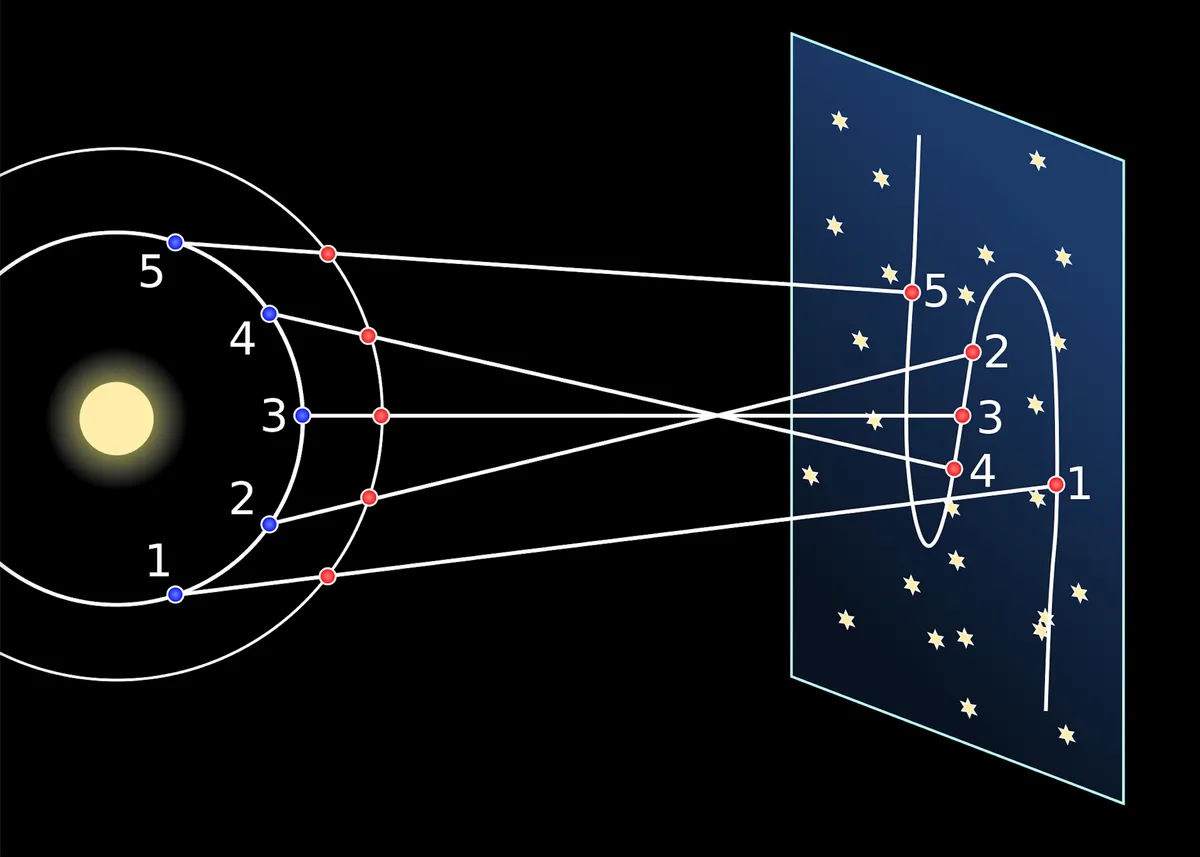

When a planet is going through a period of apparent retrograde motion, it appears as though it’s moving in the opposite direction, from east to west across the sky, often looping or zig-zagging as it goes. To the observer, this looks as though the planet is moving backwards. The word ‘retrograde’ itself, means to move backwards.

If a planet suddenly started moving backwards, it’s perhaps not surprising that our ancestors might have taken this as a sign of impending doom.

What causes apparent retrograde motion?

This backwards movement, retrograde, is actually an illusion created by our viewpoint here on Earth. It’s created by the different speeds at which the planets orbit the Sun.

When the Earth’s orbit overtakes a planet with a slower orbit, we see that planet from a different perspective. As Earth overtakes another planet, let’s say Jupiter, it overtakes on the inside and from our viewpoint on Earth, this results in Jupiter appearing to zigzag across the sky.

Think of when you overtake a vehicle on the motorway; you catch up with the other car, then you’re level with each other, and then the other car appears to move backwards as you pull ahead.

This is why you’ll often hear retrograde referred to as ‘apparent retrograde motion’ – as it only appears as though the planet is moving backwards, it’s not really.

The superior planets – any of the planets whose orbit is further away from the Sun than the Earth’s – go into retrograde around the same time as they are in opposition.

In astronomy, opposition is when a planet appears to be in the opposite direction to the Sun, as viewed from Earth. Oppositions occur approximately once a year for each planet (except Mars, which is around every 26 months), and occur as the Earth passes between that planet and the Sun. It’s also when the planet in question is closest to the Earth, making it appear bigger and brighter, so it’s an excellent time to observe these distant worlds.

Because Mercury and Venus have orbits that are closer to the Sun than the Earth’s, they can never go into opposition. However, planets closer to the Sun can go into retrograde.

When is the next retrograde in 2023?

- Mercury

- 29 December 2022 - 18 January 2023

- 21 April 2023 - 15 May 2023

- 23 August 2023 - 15 September 2023

- 13 December 2023 - 2 January 2024

- Venus

- 23 July 2023 - 4 September 2023

- Mars

- 30 October - 12 January 2023

- Jupiter

- 4 September 2023 - 31 December 202

- Saturn

- 17 June 2023 - 4 November 2023

- Uranus

- 24 August 2022 - 22 January 2023

- 29 August 2023 - 27 January 2024

- Neptune

- 30 June 2023 - 6 December 2023

- Pluto

- 1 May 2023 - 11 October 2023

Mercury in retrograde

Travelling the fastest out of all the planets, it only takes approximately 88 days for Mercury to orbit the Sun (and earning it the nickname the Swift Planet). This means it overtakes us three or four times every year, and therefore goes into retrograde three or four times a year, lasting around three weeks at a time. Of all the planets, Mercury in retrograde lasts the shortest amount of time, and in popular media, it's frequently associated with a time of disruption, but there is little (if any) scientific evidence for this.

Mercury in retrograde is relatively common, but sometimes, it will overlap with a rather exciting astronomical event: a transit. A transit occurs when the Sun, Mercury and the Earth line up, so that from our point of view, Mercury appears to move across the Sun as a tiny black disk.

Venus in retrograde

It takes 225 days for Venus to orbit the Sun and goes into retrograde every 18 months, lasting around six weeks at a time. the next time Venus is in retrograde will be in July 2023.

Mars in retrograde

Mars goes into retrograde approximately every 26 months, beginning around five weeks before opposition. Mars in retrograde lasts for a few weeks before the planet appears to move forward again. Its distinctive yellowy-orange colour makes the Mars retrograde one of the easiest to follow with the naked eye.

"Mars in retrograde is particularly obvious. The planet makes little retrograde loops in the night sky where it appears to backtrack, then carry on," explains astronomerDr Stu Clark.

"The gorgeous red colour seems to draw your attention."

The outer planets

The outer planets, also called the Jovian planets, go into retrograde less often, but appear to be moving backwards for longer – getting progressively longer the further away from Earth:

- Jupiter, the granddaddy of the Solar System, goes into retrograde every nine months or so, lasting for around four months at a time.

- Saturn goes into retrograde a little over every 12 months, lasting for around four and a half months at a time, slightly longer than Jupiter in retrograde.

- With a similar retrograde cycle to Saturn, Uranus goes into retrograde just over every 12 months, lasting for around five months.

- Like Saturn and Uranus, Neptune goes into retrograde every 12 months or so, and lasts for just over 5 months.

Pluto in retrograde

We all know Pluto should be reinstated as our ninth planet, and for those of a superstitious nature, look away: Pluto goes into retrograde for around half the year, every year. It’s the largest-known object in the Kuiper Belt (a doughnut-shaped region of icy bodies beyond Neptune) and last went into retrograde on 29 April 2022, lasting until 28 October 2022. In 2023, Pluto will go into retrograde on 1 May, remaining until 11 October.

Retrograde and the Ptolemaic model

In 150 AD, the Greek astronomer Ptolemy theorised that the Earth was at the centre of the Universe, with the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn on ‘spheres’ around the Earth, in that order. Uranus and Neptune were unknown at that time, having been discovered in 1781 and 1846 respectively.

So, with the Earth at the centre, how did the Ptolemaic model explain the apparent retrograde motion of the planets?

Put simply, Ptolemy explained this by proposing that the planets moved in small circles (called epicycles), which in turn circled the Earth on their respective spheres (cycles). The motion of the smaller epicycles neatly explained the apparent backwards movement exhibited by the bright planets.

It wasn’t until 1610 that Galileo Galilei disproved the Ptolemaic model by discovering that, like the Moon, Venus went through phases; something incompatible with Ptolemy’s take on the Solar System. If Venus was positioned, at all times, between the Earth and the Sun, then the planet would always appear as a crescent or all dark – but Galileo observed distinct phases.

Below is an animation explaining Ptolemy's model of the Universe, with Earth in the centre:

Read more: