For 40 years, the twin Voyager spacecraft have sailed through our Solar System, pushing humanity’s knowledge of the cosmos ever outward. Launched in 1977, the probes took advantage of a rare alignment of the outer planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune), flying past Jupiter in 1979, before travelling onto Saturn in the early 1980s.

Voyager 1 took a detour for a closer look at the rings, but this swung its orbit northwards out of the plane of the planets. Voyager 2 carried on alone, flying past Uranus in 1986 and Neptune in 1989, marking the end of Voyager’s planetary mission.

Read more about the Voyager mission:

But it also marked the start of Voyager’s next phase, the interstellar mission to investigate the outer regions of the Sun’s heliosphere. “The heliosphere is the bubble created by the solar wind,” says Ed Stone, Voyager’s project scientist since 1972. “The solar wind is travelling from the Sun at supersonic speeds, around 400km/s, and we knew at some point had to run into the interstellar wind.”

Voyager 1 was the first to reach the edge of the heliosphere, known as the heliopause, in August 2012. When it was 150 million kilometres from the Sun (about 120 times the Earth-Sun distance), the spacecraft detected an uptick in the number of particles originating from other stars. Voyager 2 followed suit in November 2018 when it was roughly the same distance out.

The Voyagers are now taking humanity’s first in-situ look at the cosmos beyond our local solar neighbourhood, but at more than 40 years old, the spacecraft are feeling their age. By modern standards, their instruments are simple and only capable of basic measurements of particle energies and magnetic field strength and direction.

Quick facts about Voyager

Launch dates:

- Voyager 1: 5 Sept 1977

- Voyager 2: 20 Aug 1977

Distance travelled as of January 2020:

- Voyager 1: 22,246,465,086km

- Voyager 2: 18,483,483,599km

Distance from the Sun as of January 2020:

- Voyager 1: 22,144,959,920km

- Voyager2: 18,365,602,503km

Final mission purpose:

The Voyager Interstellar Mission (VIM) aimsto extend the NASA exploration of theSolar System to the outer limits ofthe Sun’s sphere of influence,and beyond.

To make matters worse, the Voyager’s nuclear generators are running out of power, forcing the team to shut down instruments to conserve energy. Even so, they only expect the mission to last another five to 10 years.

“From an engineering point of view, it’s a new phase of the mission. We have to operate the spacecraft in conditions it was never designed for. We are doing all we can to extend our knowledge as far out into interstellar space as possible but leave it for some future mission to go further,” says Stone.

So far, only New Horizons, which flew past Pluto on 14 July 2015, has picked up that baton. It too is heading towards the heliopause, but its own power source might also give out soon. Though there are ideas for an interstellar probe that will venture out 10 times farther than either Voyager, it has yet to be selected for construction and may never come to light.

Read more about the Voyager mission's Golden Record:

Rather than lamenting their mission’s slow demise, however, the Voyager team chose to celebrate how far they’ve come.

“I think it’s a very exciting thing,” says Stone. “These are the first spacecraft to leave their stellar bubble and so now we’re learning what we can in the time we have left before they become our silent ambassadors orbiting the Milky Way for billions of years.”

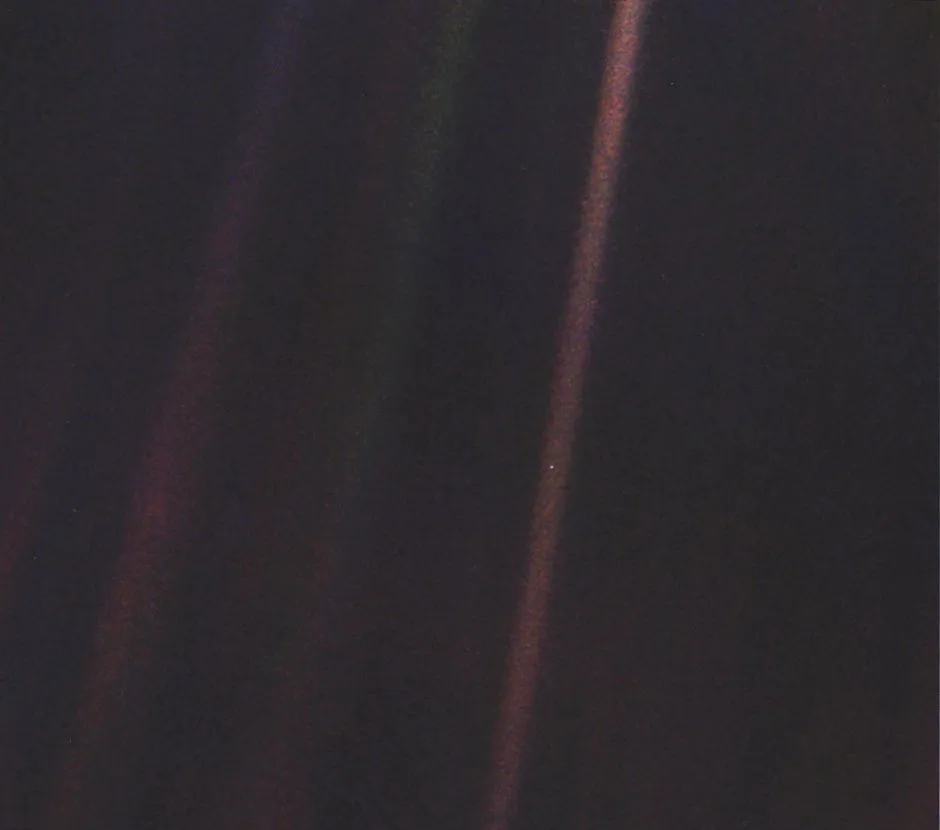

Pale Blue Dot

The iconic image snapped by Voyager

In 1990, Voyager 1 was 6.4 billion kilometres from home. Earth was already less than a pixel in size on Voyager 1’s camera. Soon it wouldn’t be visible at all. Planetary science crusader Carl Sagan suggested the spacecraft take one last snap of home.

The image, taken on 14 February, shows our planet as a single dot in the centre of an orange beam created by light scattering inside the camera. While the image has little scientific interest, its true value is best summed up by Sagan himself in his 1994 book Pale Blue Dot.

“Look again at that dot. That’s home. That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was lived out their lives… On a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam… To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known.”