Can you listen with your eyes? Can good people turn bad? Do you never forget a face? These are some of the questions that have puzzled psychologists at some point in history, and in his new book,Pavlov’s Dog, Adam Hart-Davis unearths some of the most fascinating, incredible and, quite frankly, weird things scientists have done in the pursuit of better understanding the brain.

Can you live life upside down?

How our brains interpret what we see

When you look at something, its image is projected on to your retina upside down (as it does on the sensor or film in a camera). In the late nineteenth century, the prevailing scientific theories suggested that this must be necessary if we are to ‘see’ things the right way up. However, George Stratton, a professor at Berkeley in California, questioned the current thinking, and wondered whether it is possible to live one’s life with the whole visual field upside-down. He set about constructing a pair of mini-binoculars that turned everything he saw upside down, so that the image would appear on his retina the right way up, or ‘upright’, as he put it.

Turning the world over

He placed two convex lenses of equal refractive power in a tube at a distance equal to the sum of their focal lengths. Looking through the tube turned everything upside down. He fitted together two tubes, one for each eye, and strapped the whole contraption to his head. He was careful to exclude all other light, using black cloth and pads round the edges of his device. He wore it continuously for ten hours, then shut his eyes while he removed it, and put on a blindfold so that he could see nothing. He spent the night in complete darkness.The next day he repeated the process, wearing his device all day and taking care not to see anything without it. The instrument gave him a clear field of vision and was reasonably comfortable to wear. At first he hoped to use both eyes together, but coping with two separate images was difficult; so he covered the end of the left tube with black paper, and used his right eye alone.

To begin with everything seemed to be upside down. The room was upside down; his hands, when raised into sight from below, appeared from above. Yet although these images were clear, they did not at first seem real, like the things we see in normal vision, but felt as if they were ‘misplaced, false, or illusory images’. Stratton observed that his memories of normal vision still continued to be the ‘standard and criterion of reality’ that his brain used to understand what was put before his eyes.

Memory or reality

When attempting to move around while wearing the contraption, Stratton at first blundered and stumbled. It was only when his actions were aided by touch or memory – ‘as when one moves in the dark’ – that he was able to walk or perform hand movements with any degree of success.

Stratton concluded that his problems seemed to consist entirely of the resistance offered by experience, and reasoned that someone whose vision had been upside down from the very beginning (or who had at least spent considerable time observing the world in this way) would not feel that this was unusual. Therefore he carried on this experiment for several days, and, by the seventh day, he reported feeling more at home in the upside-down scene than ever before, recording that there was by now a ‘perfect reality in my visual surroundings’.

Getting used to the view

Despite the ‘perfect reality’ of the upside-down world that he now inhabited, Stratton was still struck by just how difficult it was to operate in such an environment. Having mastered moving in the ‘wrong’ direction he still found that his perception of depth and distance was flawed: ‘my hands frequently moved too far or not far enough. . . .’ In trying to shake a friend’s hand he raised his own too high, or while brushing a speck from his paper he found he didn’t move far enough. And he still observed that his hand movements were much less accurate when he looked at them than when he closed his eyes and depended upon touch and memory to guide him.

Nonetheless, he was, however, gradually getting used to living upside down, and during his walk that evening he was able to enjoy the beauty of the evening scene for the first time since the beginning of the experiment.

Stratton’s conclusion was that it does not matter how images appear on your retina; your brain can learn to cope by using what has come to be described as ‘perceptual adaptation’ to match your vision to your sense of touch and spatial awareness.

How do you manage a democracy?

Explorations in leadership styles and good governance

1939

THE STUDY

Researchers:K Lewin, R Lippitt, and R K White

Subject Area:Social psychology

Conclusion:Effective democracy needs proactive group management rather than unlimited individual freedom.

After the pioneering psychologist Kurt Lewin escaped Nazi Germany in 1933 and fled to America, he wrote about:

. . . the peculiar mixture of desperate hope, curiosity, and scepticism with which the newly arrived refugee from Fascist Europe looks at the United States. People are fighting for it, people are dying for it. It is the most precious possession we have. Or is it but a word to fool the people? Democracy?

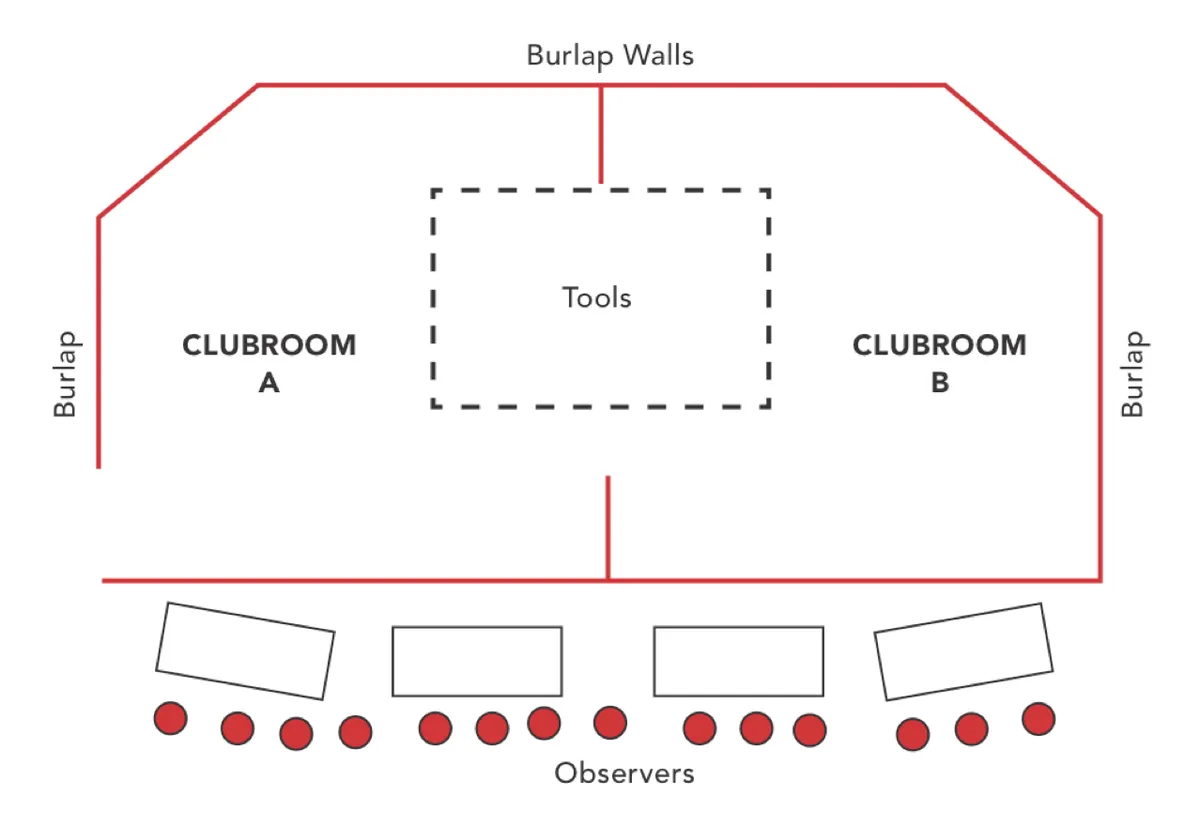

How could he learn what a real democracy was like, and how to organize it? First, he set up a ‘lab’ that was really more like a kids’ den – a space in an attic, with wooden boxes to sit on, surrounded by all sorts of junk – mainly construction equipment – and enclosed by crude sacking walls. It was crowded, undisciplined, unstructured and fun – just the opposite of a clean white classroom.

He recruited groups of 10- and 11-year-old children, and divided them into four clubs, each of which would meet once a week. The children were asked, with the help of an adult leader (who was one of the researchers) to make theatrical masks, make furniture and paint signs for the room, carve soap and wood, and

build model aircraft. In other words their club room was also their workshop.

Lewin deliberately aimed to set up different types of social climate by using different styles of leadership – groups of children would experience first one type of leader and then another, over several weeks. A dozen researchers sat in a dark corner and took notes of how the children were reacting to one another, and to the leader, while Lewin himself secretly filmed the proceedings. Interestingly, this was one of the first experiments in social psychology in which the experimenters played central parts, as leaders; before this they had merely been the observers or helpers.

Three styles of leadership

The first leader was strict; he told the children exactly what to do, step by step, so that they rarely knew what the final plan was. He told them which child should do which tasks, and exactly where they should work – mostly in the centre of the floor. In his praise or criticism he was direct and personal. He always stood in one place, wore a suit and tie and remained outside the group.

The second leader set up a ‘democratic atmosphere’ in which the entire club discussed the project in advance, and took decisions about what to do. They chose their own working groups. When they asked for advice, the leader suggested two or three options for them to choose from. He was entirely objective in his praise and criticism of their performance. He was one of the group: took off his jacket, rolled up his sleeves and moved around the space with the children, although he did little actual construction.

The third leader just sat still, let the children get on with it, and scarcely interfered at all. This ‘laissez-faire’ attitude happened originally by mistake, when a new leader, Ralph White, forgot to steer the children towards democracy, and anarchy set in. As he said later: ‘the group started to fall apart. There were a couple of kids who were realhell-raisers, and they found a great opportunity to raise hell, which wasn’t productive.’

Results

In the first regime there was endless trouble. The strict leadership led to a great deal of tension; arguments and fights broke out between the children. They were clearly unhappy, and tended to blame one another for mistakes. After one session they smashed up the masks they had been making. As Lippitt noted, ‘They couldn’t fight the leader, but they could [fight] the masks.’

In the democratic atmosphere the children were much happier, less aggressive and more objective about the work. They were also much more productive and imaginative, doing their work all over the club room.

In the laissez-faire groups, the children rarely concentrated on their tasks, but just wandered around the room. The researchers decided that this style of leadership was also interesting; so they persisted, and the leaders had to work hard at being passive and uninvolved.

When children were moved from one group to another they rapidly shifted to the new regime, and learned how to fit in with the group and the leader.

Lewin concluded that democracy would never come from unlimited individual freedom; it would need strong, proactive group management. The experiment showed that democratic behaviour can be generated in a small group, which ushered in the concept of focus groups and group therapy. More important, it showed that leadership should be a teachable skill, and need not merely be associated with charisma or military prowess.

Can you pick the logical answer?

Wason’s Selection Task: ABSTRACT REASONING IN CONCRETE TERMS

1971

THE STUDY

Researchers:Peter Wason and Diana Shapiro

Subject Area:Cognition, decision-making

Conclusion:We struggle with abstract problems, but the same problem becomes easy when expressed in concrete terms.

Try this logic problem:

Every card is coloured on one side and has a number on the other. All blue cards should have an even number on the back. Which of these cards would you have to turn over to find out whether that is true?

Beware; at least 70 per cent of people get this wrong. Which cards would you turn over?

Peter Wason was interested in how people tackle logical problems, and first introduced some like this in 1966. He explained how to approach it in terms of pure logic, which you may or may not find helpful.

In this example,pis the blueness of the card, andqis the evenness of the number; sopis true for the first card and false for the second, andqis true for the fourth card, but false for the third. Therefore you have to turn over the blue card, to see whether it has an even number on the back. You also have to turn over the 3 card, because that is an example ofqbeing false; 3 is not an even number. Turning over the 8 card does not help, for if it is blue that is fine, but if it is pink (or any other colour) that is still fine; it does not contravene the rule.

So the correct cards to turn over are blue and 3.

Wason and Shapiro gave students a total of 24 tests like this one. There were only seven correct answers (29 per cent). The students were too concerned with verifying the rule, and ignored the possibility of falsification. In other words, they ignored the chance to falsify the rule by turning over theqfalse card.

The researchers wondered whether the problem might be easier if it was related to the real world, and devised what they called ‘thematic’ problems. They divided 32 undergraduate students into two groups. Those in the abstract group were given a task like the one above: four cards had a letter on one side and a number of the other. They were showing D, K, 3 and 7. The rule was ‘Every card with a D on one side has a 3 on the other.’ Which cards do you have to turn over to decide whether it was true or false?

Can you solve it? The answer is at the end of this entry.

Those in the thematic group were told that the experimenter had made four journeys on particular days. She claimed that every time she went to Manchester she travelled by car. Four cards represented her journeys; each had a town on one side and a mode of transport on the other: which cards would they have to turn over to verify her claim?

Results

The abstract group averaged only two correct (12.5 per cent). The thematic group did much better, with ten correct (62.5 per cent). The researchers concluded that the thematic problem is easier because it deals with concrete material rather than abstract letters and numbers, and also has a relationship between the words; they are all about travel, and situations that could happen in real life.

But the easiest of all is a situation that happens all the time when you go out drinking. Suppose you are in a bar, where no one under the age of 21 is allowed to drink beer. Each card represents one drinker:

Which cards do you have to turn over to find out whether these four are obeying the law? You should find this one easy.

The conclusion seems to be that we can solve such problems easily when they involve social compliance. This might be because we are more familiar with social situations, or because our brains have evolved to solve social problems, rather than abstract ones.

Answers

The correct answers are D and 7,

Manchester and train, and Beer and 17.

For more psychology reads, check out 7 must-read psychology books to help you better understand yourself and your potential.

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook,InstagramandFlipboard