“What ice cream flavours have you got for dessert?”

“Hazelnut. Or strawberry and… erm, I’ve forgotten! Let me just go and check.”

Joy heads off to the kitchen, returning a minute later.

“Strawberry and white chocolate.”

So far, so normal. What waitress or waiter doesn’t forget the odd detail on the menu? In fact, our whole meal has been completely hitch-free. Nothing amiss, no spillages… not bad going for a place that calls itself The Restaurant That Makes Mistakes.

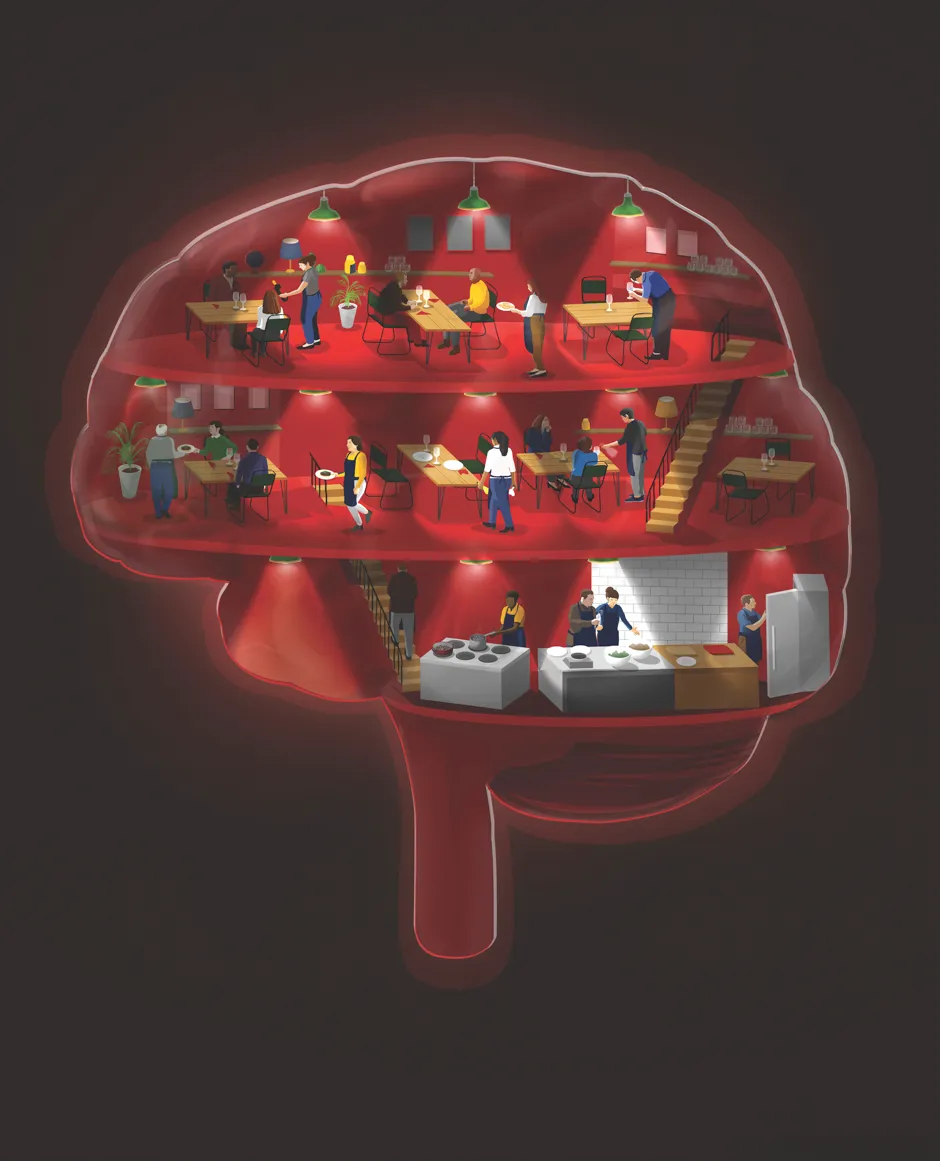

This is no ordinary restaurant. It’s run by Michelin-starred chef Josh Eggleton, and all 14 of his chefs and waiting staff are volunteers living with dementia. The pop-up restaurant is the brainchild of CPL Productions, which is filming a Channel 4 series looking at how people with dementia might benefit from staying in work. Celebrities such as Downton Abbey’s Hugh Bonneville have already stopped by for a slap-up meal.

Read more:

I tucked into mushrooms with lovage, followed by ox cheeks with gratin, then finished off with the aforementioned ice cream. If I didn’t know in advance – and turned a blind eye to the TV camera lurking behind a curtain – I’m not sure I would have noticed anything different about this restaurant.

The volunteers have certainly risen to the challenge. But it hasn’t all been plain sailing. “It’s been stressful, because I’ve had good days and bad days,” Joy tells me. “On a bad day, I can’t think straight, my head is foggy, and everything I do takes 10 times longer. To actually plan anything some days is impossible. Other days, I can get through and enjoy every moment. Today is a positive day.”

What is dementia?

Some 850,000 people are estimated to be living with dementia in the UK, and that’s expected to rise to two million by 2050. Most of us probably know, or have known, someone with dementia. But we may not understand the difference between dementia and, say, Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia describes the symptoms that someone experiences as a result of a brain disease. Such symptoms can include memory loss, mood and behavioural changes, and difficulties with thinking, problem-solving and language. More than 100 diseases can cause dementia, each with slightly different symptoms.

The most common cause of dementia is Alzheimer’s, which is what Joy has been diagnosed with. After diagnosis, she had to give up her job working in care. “Having looked after people with dementia, I knew exactly what I could be facing,” she says.

Joy is not alone in losing her job in the wake of her diagnosis. Of the 40,000 people with dementia in the UK who are under the age of 65, only 18 per cent carried on working after they were diagnosed. By 2020, one-third of the UK workforce will be 50 or over, and many will go on to develop some kind of dementia. Rather than having to leave their job, could these people be better integrated into their workplace? One of the goals of the Channel 4 series is to encourage employers to take on staff with dementia, or keep current employees after a diagnosis.

“Many of the volunteers admitted to feeling isolated and unsupported by the welfare system, feeling like they’d been thrown on the scrapheap,” says Louise Bartmann, producer of the series. “After a diagnosis, many of them lost their job, their ability to drive, their independence, their identity and, in some cases, their friends and family. The restaurant has given the volunteers a sense of purpose.”

To cater for the volunteers, the restaurant made some small adjustments, such as labelling objects like the coffee machine and the cutlery tray. To help locate their belongings in the staff room, each volunteer has a photo of themselves on their locker. They’re also each given a notebook, so they can write things down, such as recipes and what items need to be laid on the table, as well as ‘memory books’ to help them remember things like the names of their colleagues.

“The volunteers say they feel more confident,” says Bartmann. “For some, this is demonstrated through their verbal fluency, whereas for others it is being visibly happier.”

Read more:

- In Pursuit of Memory: The Fight Against Alzheimer's

- Mice study suggests green tea and carrots may help to reduce Alzheimer’s-like symptoms

“I think it’s important that everyone realises that we can’t do stuff on certain days,” says Joy. She is quick to sing the praises of the support offered by the television team. “There’s always someone on hand for us. One day, I fell apart and there was someone there within seconds. We’ve got a chaperone at the hotel overnight [to ensure the volunteers are looked after away from home]. The team’s vision has been second to none.”

The Alzheimer’s Society has drawn up a guide for employers to help them integrate workers with dementia. Suggestions include changes such as making signs clearer and improving acoustics, as well as less tangible things such as carrying out surveys to find out how many of the staff are actually affected. And, crucially, being careful with language – avoiding phrases such as ‘dementia sufferer’, ‘demented’ or ‘burden’.

As The Restaurant That Makes Mistakes has shown, having a job and feeling useful can be hugely beneficial to people with dementia. But research has found that it can also help to do something creative – whether that’s through music or art.

Creative thinking

Dementia can cruelly rob people of their ability to communicate properly. However, people with dementia whose language skills have failed can still use art as a tool to communicate with loved ones, according to a 2013 study at St Michael’s Hospital in Toronto. In the case of Alzheimer’s disease, some researchers believe that art therapy may enable people with dementia to communicate using regions of the brain that have remained relatively healthy.

In 2016, a group of scientists, artists and musicians set up a two-year initiative called Created Out Of Mind at London’s Wellcome Collection, with the aim of using the creative arts to explore and challenge people’s understanding of the different types of dementia. Over the course of the two years, more than 1,000 people with dementia benefited from its variety of artistic and musical experiences.

One of the projects worked with people living with a rare form of dementia called posterior cortical atrophy (PCA). PCA iscaused by shrinkage at the back of the brain, which can lead to visual problems such as trouble with recognising faces and judging distances. It is difficult for people to communicate the experience of these problems to others: they can’t just amend a photo to show what their world looks like.

Read more:

Through the Created Out Of Mind project, a filmmaker interviewed people living with PCA and created an animation called Do I See What You See? The animation was a success: one woman, whose husband lives with PCA, showed it to the hospital staff looking after him while he had a hip operation, and it helped the nurses tailor their care to his needs.

Another project used technology to gather data on how music can help. Singing With Friends is a choir made up of people with dementia. Choir members were asked to wear wrist sensors to monitor their heart rate and skin conductance, which is a measure of arousal. The results are still being analysed, but initial feedback supports what everyone involved in Singing With Friends can see: singing has a positive physiological effect on people with dementia. This also ties in with research showing that singing in choirs more generally can improve mood and wellbeing.

“People with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, for example, often have brain impairments in coding new information, but their emotional processing systems are still very much intact,” says Prof Sebastian Crutch, a neuropsychologist at University College London and director of Created Out Of Mind. “So why wouldn’t those people be given the opportunity to take part in a choir? They may not be able to recall the factual details of exactly what happened and when, but they frequently make statements like, ‘I remember how I felt’.”

Music for the mind

Indeed, there is a growing body of evidence that shows music can significantly improve the lives of people with dementia. A study carried out last year at the University of Utah found that music stimulates various areas of the brain simultaneously, including parts which are the last to be affected by dementia. Back here in the UK at the University of Worcester, meanwhile, doctoral researcher Ruby Swift is finding that compiling music playlists can help people with dementia to connect with others in their lives.

“Music maintains a kind of neural robustness in the brain, and there are still often some fairly strong links between music and memory,” she says. “Memories evoked by hearing music or humming a familiar tune can help people to reminisce about their past, opening up new conversations and friendships.”

A recent House of Lords inquiry looked into the untapped potential of music to enhance the wellbeing of people living with dementia. Off the back of this, the Music for Dementia 2020 campaign is asking the Department of Health and Social Care to enable music to be ‘socially prescribed’. In other words, instead of being given medication, which may have a limited effect, someone with dementia might be teamed up with a local music therapist, or offered access to a music group or choir.

Challenging perceptions

The key message of all these different projects seems to be that cultural perceptions need to change so that people living with dementia can reap the benefits of being better integrated in society, whether that’s through work or the arts.

“We need to break down any taboos or stigma about what dementia is or isn’t, and that includes that it’s only a disease for old people,” says Tim McLaughlin, operations director at the Alzheimer’s Society. “Let’s make sure that, before dementia takes away these people’s individuality and independence, society does not remove them first.”

Crutch agrees: “Frequently, people living with dementia talk about a sense of social disconnection. They get a diagnosis and, suddenly, they’re talked about as a patient, not a person. The key is to encourage the public to think twice about what opportunities people with dementia might be given, so that they can continue living as the people they are and will be – not just the people they were.”

- The Restaurant That Makes Mistakeswill be shown onChannel4in June.

- This page has been updated to correct the name Ruby Smith to Ruby Swift.

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard