BBC presenter Naga Munchetty shared one of her “most traumatic physical experiences" on 21 June, on her Radio 5 Live programme. A few years ago, Munchetty had a contraceptive intrauterine device – an IUD – fitted by her GP, and she was inspired to speak about what happened during this procedure after reading Caitlin Moran’s column in The Times where the journalist and author described an experience that resonated harrowingly with her own.

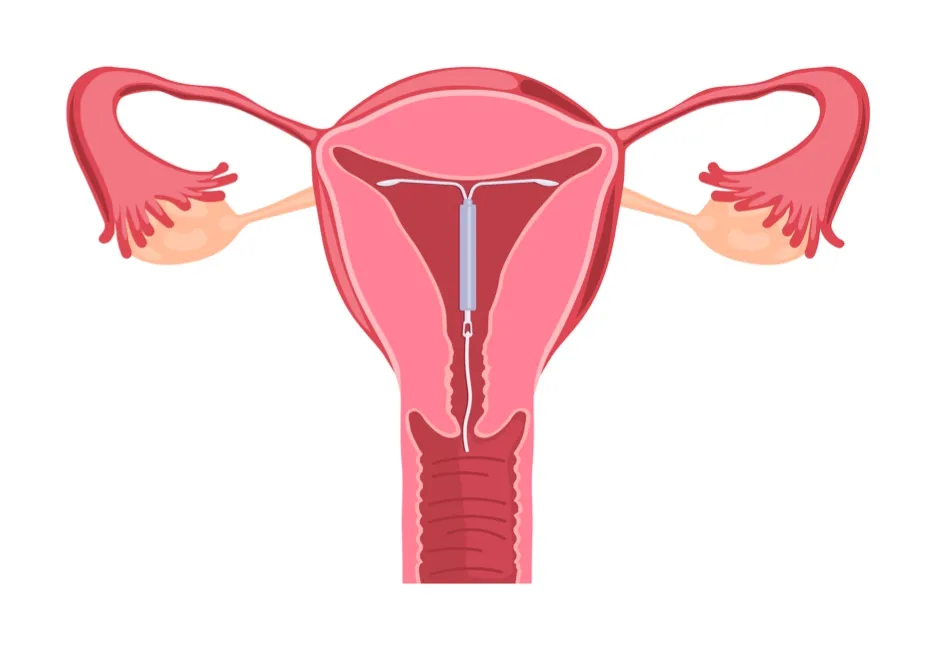

Munchetty’s cervix was dilated so that the IUD, a 32mm T-shaped device made of plastic wrapped with copper wire, could be inserted into her uterus. The pain was so excruciating that Munchetty’s screams “horrified” those in the waiting room, including her husband who was waiting to take her home.

The GP and the nurse accompanying her were compassionate. Halfway through, Munchetty was asked if she wanted to stop – but having endured the procedure thus far, she felt “determined” to continue. At no point was any form of pain relief, such as a local anaesthetic or a sedative, offered to her. Before the procedure was over, Munchetty fainted twice.

Munchetty emphasised that the IUD – or ‘coil’ – is a safe and effective method of long-acting reversible contraception. The IUD can remain in place for between 5 and 12 years, and if it is inserted correctly, it is over 99 per cent effective at preventing pregnancy – making it the most efficacious form of long-term birth control apart from sterilisation.

Read more about contraceptives:

- Once-a-month contraceptive pill could have 'tremendous impact on global health'

- Why is it so difficult to make a contraceptive pill for men?

Having an IUD is convenient and involves fewer complications than some other contraceptive methods; there is no pill to remember to take every day, and no interruption to sexual intercourse – although it does not protect against sexually transmitted diseases. IUD insertion has been associated with pelvic inflammatory disease, but studies have shown the risk is negligible. One in 20 IUDs fall out of the uterus – but it doesn’t cause the kind of side-effects associated with hormonal contraceptives, including blood clots.

Long-term side effects, when they do occur, are usually dysmenorrhea (menstrual pain), cramps and heavy/intermittent bleeding. It is these symptoms that have been cited as the main reasons people opt for early removal, but symptoms can decrease over time and severity seems to be impacted by age.

Of all available contraceptives, the copper IUD has one of the highest continuation rates, with 84 per cent of people sticking with the device past 12 months. According to one study, 65 per cent of people were 'very satisfied' with the IUD, which sounds low, but other common contraceptives such as the pill and the implant have similar figures: 41 per cent and 54 per cent respectively.

How does the copper coil work?

Unlike the combined pill, which contains synthetic oestrogen to suppress ovulation, and the intrauterine system – a type of IUD that releases progesterone – the copper IUD doesn’t utilise hormones to prevent an ovum being fertilised or implanting in the uterus.

Copper produces an inflammatory reaction in cervical mucus that is effectively toxic to sperm, making it extremely difficult for sperm to survive and reach the fallopian tubes. If fertilisation does occur, the IUD can prevent an ovum implanting – for this reason, it is recommended as a reliable emergency contraceptive.

The IUD can be removed at any time; its position is located by two nylon guiding threads through the cervix. Recent studies show that once removed, it does not tend to interfere with future fertility. Its relative safety, efficacy and low-maintenance benefits have contributed to the IUD becoming the most popular long-term contraceptive in the world since being introduced for medical use in the 1970s – an estimated 159 million women aged between 15-49 use a form of IUD.

Munchetty did not share her traumatic experience to discourage people from choosing an IUD, or to detract from the evident advantages of this contraceptive. “What this is about is not the coil itself,” she said. “What this is about is how we look at all women’s health and pain.”

The Gender Pain Gap

For Munchetty, and many other women, the agony of IUD insertion is emblematic of wider failings in the medical treatment, recognition, and validation of female pain. The Gender Pain Gap, a term that has gained traction over the last two decades, acknowledges how women’s pain is more frequently delegitimatised, downplayed, and dismissed by health professionals.

Since the influential study ‘The Girl Who Cried Pain: A Bias Against Women in the Treatment of Pain’ by health care law and ethics experts Diane Hoffmann and Anita Tarzian was published in 2001, awareness has grown around the ways that negative stereotypes of women’s pain impact how they are treated by health professionals and in clinical settings. Hoffmann and Tarzian revealed that assumptions about women’s sensitivity and emotionality contributes to the increased likelihood of their pain being attributed to psychological factors such as anxiety rather than physical causes.

A 2018 analysis of pain and gender literatureby Swedish researchers of social medicine, showed that women’s pain is more frequently “psychologised” and “taken less seriously” compared to men’s pain. Both studies showed that the more ‘feminised’ ways women tend to express pain, both verbally and non-verbally, contributed to judgements about how credible, legitimate and worthy of further diagnostic investigation their pain was perceived to be.

Attributing women’s descriptions of pain to their emotions rather than their bodies contributes to delayed and missed diagnoses across a range of health conditions, illnesses and diseases.

Of course, pain is entirely subjective and unique to the individual sufferer. How a patient’s descriptions of pain are interpreted and responded to is dependent on an intricate balance of communication and listening – and evidently, women face greater obstacles when trying to communicate their pain and be listened to. The Gender Pain Gap is largely the result of medical and cultural biases against the perceived validity of women’s pain, and the attitudes around IUD insertion illuminate an insidious aspect of this disparity.

When it comes to processes and procedures associated with the so-called “natural” functions of the female body – especially related to gynaecological and reproductive health – women’s pain is often minimised, normalised, and undervalued.

As Munchetty stated, “…some women feel, or are made to feel, that their pain is something to endure, not a problem to solve…” There is an ingrained narrative that women should ‘grin and bear’ the potential pain of an invasive gynaecological` procedure like IUD insertion in order to gain the sexual and reproductive autonomy, and health benefits, that this contraceptive can offer.

As Lucy Cohen, who recently launched a public survey after an “excruciatingly painful” IUD insertion, stated in an interview. “There seems to be a culture that the pain and suffering is worth it if the end justifies the means. But surely, we can have the end result with the means being properly managed for pain? Why should women suffer unnecessarily?”

Read more about pain:

- How your brain creates pain – and what we can do about it

- 'Off-switch' for pain found in mice brains

Cohen, who shared her experience on Munchetty’s Radio 5 Live show, opted to use the IUD for its long-term benefits, and because hormonal contraceptives are not suitable for her. Cohen, like Munchetty, was prepared for a “routine procedure” described by many doctors, and on the NHS website, as being potentially “uncomfortable".

She asked her doctor about pain relief, but was told “paracetamol would be enough.” During the insertion, which took three attempts because she has a “tilted cervix”, Cohen was “shocked at the noises coming from my mouth. I was in so much pain that I did not recognise my own voice.”

Of course, some women do experience levels of discomfort and cramping during the insertion that they feel they can manage without pain relief. But the narrative perpetuated by clinicians and doctors that “having a coil fitted should not be traumatic or painful”, or that “most people encounter no problems”, can be a harmful one. Cohen told Munchetty that the degree of pain she suffered made her feel like “an anomaly”. She was not offered any form of pain relief during the insertion. “Nobody ever told me it was going to be horrific or that it could be excruciatingly painful," she said.

Cohen’s survey has garnered responses from nearly 1,500 women. Of the responses, 93 per cent reported pain during IUD insertion, with more than 25 per cent of those describing that pain as “almost unbearable” and “excruciating”. Out of those surveyed, 71.18 per cent said they did not feel adequately informed of what to expect.

Why is the IUD painful?

Each stage of the procedure to insert – as well as remove - an IUD can cause pain.

First, the cervix is dilated with a speculum. The cervix is then stabilised with a tenaculum, an instrument similar to forceps. A uterine sound, a tube used to measure the depth of the uterus and cervical canal, indicates where the IUD should be placed.

Finally, the IUD itself, through an insertion tube, is embedded into the correct position in the uterus. If the potential pain of any of these stages is minimised, downplayed or not accurately explained, then women are not being given the opportunity to make informed choices about their own bodies.

Although the NHS states that “you can have a local anaesthetic to help”, Munchetty, Cohen and the thousands of women who have spoken out about the trauma of IUD insertion have demonstrated that pain relieving options – including injections, sprays and gels – are not offered by all NHS clinics and GP practices.

In a statement released on 22 June by the Royal College of Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) and the Faculty for Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (FSRH), Dr Diana Mansour, Vice President of the FSRH, explained that she always offers “pain relief before and, where necessary, during an IUD placement including the use of local anaesthesia”.

Mansour also enables her patients to explore other options “such as having the IUD fitted under conscious sedation or general anaesthesia in the local hospital”.

All women who choose to use an IUD should be supported in this way, free of the shame and silencing that can hinder women’s autonomy over their bodies, and their pain.

Thanks to the bravery and courage of those speaking out about IUD insertion, a much needed and overdue conversation around women’s rights to not endure pain has been raised. As Munchetty said on her show, “lots and lots of women have no problem at all”; but, she added, “like all medical procedures, there’s a vast range of experiences.” Providing all women with clear, accurate, comprehensive information about IUD procedures, as well as discussing pain relief options in advance, is not fearmongering.

Rather, this will ensure women are empowered and respected to make informed choices about their reproductive and sexual health, safe in the knowledge that their unique relationship to pain is taken seriously, their individual experience is valued, and their own voices are heard.

The strength of responses to the IUD insertion debate makes it clear that women need the space to speak out when it comes to medicine’s ingrained mistreatment of their pain. And when women are regarded as reliable narrators of their body experiences, they provide the insights and knowledge needed to forge meaningful change in a medical culture that has, for too long, maligned their pain as a burden, or minimised it as the inevitable consequence of being female. Listening to women, and believing them, is an important step towards a more respectful, attentive, and compassionate relationship between medicine practice and women’s pain.

Elinor Cleghorn is the author of Unwell Women: A Journey Through Medicine and Myth in a Man-Made World (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, £16.99).

- Buy now from Amazon UK, Bookshop.org and Waterstones