Until Neanderthals’ disappearance some 40,000 years ago, they were our closest relatives. But ever since we discovered this hominin species in 1856, we’ve tended to stereotype them as brutal, unsophisticated ‘cavemen’. This is a view that’s now looking increasingly outdated.

As scientists reveal new insights into Neanderthals’ lives – from their use of plants, to their family life and their artistic skills – the notion that they were an inferior species is being debunked once and for all. Rebecca Wragg Sykes, an archaeological researcher specialising in Neanderthals, updates our understanding of ancient humans.

1

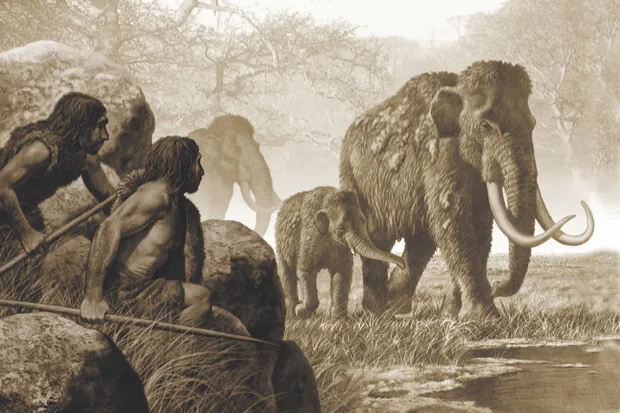

They were gourmets

Neanderthals lived across Eurasia, from North Wales to Palestine, and all the way into Siberia. With such a colossal range, it’s no wonder that they ate a variety of foods. They hunted cooperatively in groups to capture formidable creatures such as bears, rhinos, and giant camels (now extinct). They fashioned wooden spears for close-quarters jabbing, while others they threw like lances. After the kill, they deployed expert skills to skin and butcher their prey, removing the fattiest meat from haunch to brain, even smashing and possibly boiling bones for their nutritious marrow.

As well as big game, Neanderthals caught rabbits and birds, and collected shellfish. Fruits and nuts, including pistachios, walnuts, pine nuts, date palm, figs, olives and grapes, also played a surprisingly large role in their diet. Meticulous examinations of distinctive wear patterns and microscopic residues on their teeth published in 2018 have confirmed that foods which needing peeling or hulling like tubers (wild radish, water lily) and seeds (wild cereal, peas, lentils) were on the menu right across Europe. We’ve even found evidence at sites as far apart as Belgium and Iraq that they cooked plants, from dry-roasting to boiling. It seems that no matter when or where they lived, Neanderthals took full advantage of nature’s bounty.

Read more:

- Ancient Neanderthal-Denisovan hybrid unearthed in Siberian cave

- Human diseases from Africa could have wiped out Neanderthals

2

They were artists

There’s evidence that Neanderthals were creative, with an understanding of symbolism. In the past decade, a flurry of sites have revealed that they collected bird feathers and talons. Meanwhile, meticulously carved stones and bones have been found that have no obvious practical explanation.About 50,000 years ago, Neanderthals engraved the stone floor of a cave in Gibraltar to create a ‘hashtag’ design (a strange echo of 21st-Century life).

We’ve also been finding pigments. Practical uses for the pigments are possible, such as ingredients in glues for tool-making, but some examples are hard to argue as utilitarian. These include a fossil shell in Italy smeared with red ochre at least 45,000 years ago, and shells discovered in Spain with yellow and red pigments mixed with the sparkly mineral pyrite.

Just this year, paintings in three Spanish caves were dated to more than 10,000 years before Homo sapiens are known to have been in this part of the world. The discoveries include painted stalagmites, a vertical red line and the shape of a hand outlined by red paint. If the dating is correct, then this could mean that when humans entered Europe, they found caves already filled with Neanderthal art.

3

They had families

Neanderthals seem to have lived in small, family-orientated groups, with daily lives built on close emotional bonds. Birth was probably risky, and infants would have needed nursing and carrying for more than a year. Children joined in adult activity early: heavy work marked their bones, and tiny scratches on their teeth show that they learnt to eat with stone knives.

At the end of life, we know that Neanderthal death traditions were complex. Scrutiny of bones from across Europe has identified cut marks showing that the bodies of the deceased were often carefully taken apart, and sometimes even eaten – a way of coping with death that’s more common in history than you might think.

But Neanderthal relationships weren’t limited to their own species. In 2010, it was revealed that modern humans (Homo sapiens) interbred with them, and genes moved in both directions. In 2015, genetic analysis of a 40,000-year-old human jawbone from Romania found Neanderthal ancestry within only six generations.

Finding such a close relationship by chance in some of the oldest European human remains is unlikely, so interbreeding was probably common at this time. The amount and diversity of Neanderthal genes in our DNA points to hundreds – if not thousands – of human-Neanderthal encounters. We don’t know who raised the resulting offspring, or if groups lived and socialised together, but these babies would have required the same devoted care and love as our own.

4

They were creative

One of the most persistent myths about Neanderthals is that their technology was static and simple. In fact, we see clear changes over the hundreds of thousands of years they existed, from the way they knapped (shaped pieces of stone to make tools and weapons) to the specific products they made.

Neanderthals were innovators, too: they developed the ‘Levallois technique’ of knapping, which allowed greater control in the size and shape of the pieces they removed from stone blocks, and invented the first synthetic material, ‘birch tar’. This was distilled from the bark of birch trees with carefully controlled fires, and used as a glue for tool handles.

Neanderthals also worked with materials other than stone. They selected bones for their knapping kits, and sometimes shaped them for smoothing tasks, which probably included working animal hides into furs and skins.

Just like many traditional societies today, Neanderthals also used their mouths as a ‘third hand’ when cutting things, which left tiny scratches on their teeth. Some Neanderthal women have been found to have scratches that were shaped differently to those of the men, suggesting that they had their own specific tasks.

Read more:

5

They were medics

We can reconstruct a jaw-dropping amount of information about Neanderthals from their teeth: tiny grooves reveal where enamel growth was affected by severe illness or malnutrition. A 2017 study analysing the dental tartar of Neanderthals from El Sidrón, Spain, found DNA from multiple bacteria, including those causing gum disease, diarrhoea, and whooping cough. Intriguingly, one adult with a tooth abscess was also found to have DNA from a Penicillium mould (a natural source of penicillin) in his tartar. This may have been eaten by chance, but it’s just possible that this Neanderthal was self-medicating.

Elsewhere, there are at least two cases of injured arms being amputated, while a number of individuals have been discovered with severe injuries that probably meant they were temporarily unable to walk, requiring medical care.

We also know that Neanderthals collected and chewed bitter plants like chamomile and yarrow. Neanderthal DNA tells us that they had taste receptors for the acrid compounds in these plants, so it’s possible that they consumed them for medicinal rather than culinary purposes.

6

They didn’t disappear

Neanderthals never really went extinct, at least not genetically. Between 20 and 70 per cent of their genome lives on in us, spread among various human populations in Eurasia. In terms of quantity of DNA, there are actually more ‘Neanderthals’ around now than ever. Yet between 40,000 and 35,000 years ago, their fossils disappeared from the record, so the question is: why did we absorb them into our species, and not the other way around?

Proposed theories for our potential superiority have included a broader diet, more efficient tool manufacturing, and even a mastery of symbols and art. But these all look less certain in light of the evidence described in this article, and it’s likely that a number of effects played a role.

While Neanderthals had lived through many periods of extreme climate change, the conditions around 55,000 years ago became extraordinarily unstable. If Homo sapiens had even marginal advantages in coping with this instability – perhaps more effective weaponry (allowing us to obtain more food), or extended social networks – then over time this would have built up.

On millennial scales, a few extra human babies surviving per year could eventually snowball into a total population replacement, especially if Neanderthals’ genes were being diluted by breeding with us. Their fate wasn’t a dramatic annihilation, but a slow, irreversible assimilation.

- This is an extract from issue 327 ofBBC Focusmagazine -subscribe here